Low deforestation countries to see least benefit from carbon trading

Low deforestation countries to see least benefit from carbon trading

mongabay.com

August 13, 2007

Compensation for global warming mitigation through carbon offsets could bypass those countries that are the most deserving

Countries that have done the best job protecting their tropical forests stand to gain the least from proposed incentives to combat global warming through carbon offsets, warns a new study published in Tuesday in the journal Public Library of Science Biology (PLoS). The authors say that “high forest cover with low rates of deforestation” (HFLD) nations “could become the most vulnerable targets for deforestation if the Kyoto Protocol and upcoming negotiations on carbon trading fail to include intact standing forest.”

Carbon emissions from deforestation are one of the largest sources of greenhouse gases, accounting for around one fifth of total annual emissions from anthropogenic activities. Carbon emissions from tropical deforestation are expected to increase the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration by 29 to 129 ppm within 100 years. Concentrations presently stand around 380 ppm.

To slow emissions from deforestation and other forms of land use change, scientists and policy makers have proposed an “avoided deforestation” initiative whereby tropical countries would be compensated by reducing their deforestation rates (RED). Compensation would come through carbon credits which companies in industrialized countries could use to offset their emissions. As currently proposed, compensation would be tied to historical deforestation rates, a link that sets up a troubling paradox: tropical countries will be presented with significant financial incentives to ramp up forest clearing until the framework takes effect in order capture the highest value from reducing deforestation from their historical baseline.

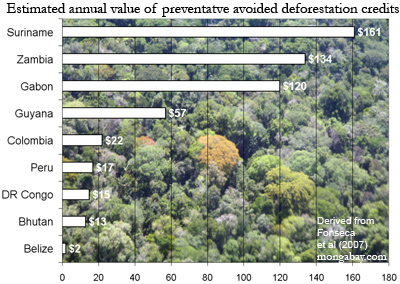

The value (in $US millions) of avoided deforestation credits to HFLD countries. Estimated by da Fonseca et al (2007) assuming a reference emission rate of one-half of the global average deforestation rate (-0.11%/year) for HFLD countries and a carbon price of US$10 per ton of CO2) |

The new PLoS paper argues that “preventive credits” could help avoid this temptation, while at the same time rewarding countries that have effectively protected their forest cover.

“Since current proposals would award carbon credits to countries based on their reductions of emissions from a recent historical reference rate, HFLD countries could be left with little potential for RED credits. Nor would they have the potential for reforestation credits under the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism,” wrote the authors. “Without the opportunity to sell carbon credits, HFLD countries would be deprived of a major incentive to maintain low deforestation rates. Since drivers of deforestation are mobile, deforestation reduced elsewhere could shift to HFLD countries, constituting a significant setback to stabilizing global concentrations of greenhouse gases at the lowest possible levels.”

“The minute that you exclude those countries, their forests lose economic value in the global carbon market, leaving governments with little reason to protect them,” said study lead author Gustavo Fonseca, a scientist at Conservation International (CI) and Brazil’s Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais.

HFLD countries — consisting of Panama, Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Peru, Belize, Gabon, Guyana, Suriname, Bhutan and Zambia, along with French Guiana — contain 20 percent of Earth’s remaining tropical forest and 18 percent of tropical forest carbon.

“Given the very large — and likely still underestimated — role of tropical deforestation in causing climate change, these forest-rich countries should be at the forefront of worldwide efforts to sequester carbon, rather than being left out entirely,” said co-author and CI President Russell A. Mittermeier.

The study estimates that at $10 per ton of CO2, preventative credits could be worth US$365 million to $1.8 billion annually to HFLD countries, depending on how compensation is calculated.

While the authors are hopeful for preventative credits, they caution that policymakers would need to proceed carefully.

“Introducing an additional source of carbon credits could lower the price of carbon, weakening the incentive to reduce deforestation in countries where rates are high,” they wrote. “However, preventive credits should be evaluated in light of their net effect in reducing global CO2 emissions. The volume of preventive credits necessary to create an advance incentive against deforestation in HFLD countries would be 10—49 million tons of carbon annually, depending on which reference rate is selected. This is equivalent to just 1.3%—6.5% of developing countries’ emissions from deforestation. The greater the global demand for carbon credits, the less impact this increase in supply would have on carbon price. In return, preventive credits would extend substantial protection to nearly one-fifth of tropical forest carbon.”

CITATION: Gustavo A. B. da Fonseca, Carlos Manuel Rodriguez, Guy Midgley, Jonah Busch, Lee Hannah, Russell A. Mittermeier (2007). No Forest Left Behind. PLoS Biol 5(8): e216 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050216

Related articles

|

Reducing tropical deforestation will help fight global warming

(5/10/2007) Scientists have lent support to a plan by developing countries to fight global warming by reducing deforestation rates. Tropical deforestation releases more than 1.5 billion metric tons of carbon into the atmosphere every year, though in some years, like the 1997-1998 el Nino year when fires released some 2 billion tons of carbon from peat swamps alone in Indonesia, emissions are more than twice that. Writing in the journal Science, an international team of scientists argue that the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation (RED) initiative, launched in 2005 by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, is scientifically and technologically sound, and that political and economic challenges facing the plan can be overcome.

Is peat swamp worth more than palm oil plantations?

(7/16/2007) Could peat swamp be worth more intact for their carbon value than palm oil plantations for their oil? Quick analysis suggests yes, though binding limits on emissions will be needed to trigger the largest ever flow of money from the industrialized world to developing countries. At stake: the bulk of the world’s biodiversity.

Papua seeks funds for fighting global warming through forest conservation

(8/10/2007) In an article published today in The Wall Street Journal, Tom Wright profiles the nascent “avoided deforestation” carbon offset market in Indonesia’s Papua province. Barnabas Suebu, governor of the province which makes up nearly half the island of New Guinea, has teamed with an Australian millionaire, Dorjee Sun, to develop a carbon offset plan that would see companies in developing countries pay for forest preservation in order to earn carbon credits. Compliance would be monitored via satellite.

|

Globalization could save the Amazon rainforest

(6/3/2007) The Amazon basin is home to the world’s largest rainforest, an ecosystem that supports perhaps 30 percent of the world’s terrestrial species, stores vast amounts of carbon, and exerts considerable influence on global weather patterns and climate. Few would dispute that it is one of the planet’s most important landscapes. Despite its scale, the Amazon is also one of the fastest changing ecosystems, largely as a result of human activities, including deforestation, forest fires, and, increasingly, climate change. Few people understand these impacts better than Dr. Daniel Nepstad, one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest. Now head of the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon program in Belem, Brazil, Nepstad has spent more than 23 years in the Amazon, studying subjects ranging from forest fires and forest management policy to sustainable development. Nepstad says the Amazon is presently at a point unlike any he’s ever seen, one where there are unparalleled risks and opportunities. While he’s hopeful about some of the trends, he knows the Amazon faces difficult and immediate challenges.