U.S. can cut oil imports to zero by 2040, use to zero by 2050

U.S. can cut oil imports to zero by 2040, oil use to zero by 2050

mongabay.com

March 29, 2007

The United States could dramatically cut oil usage over the next 20-30 years at low to no net cost, said Amory B. Lovins, cofounder and CEO of the Colorado-based Rocky Mountain Institute, speaking at Stanford University Wednesday night for a week-long evening series of lectures sponsored by Mineral Acquisition Partners, Inc.

Lovins opened by comparing the current position of the oil industry to that of the whaling industry in America in 1850, when it was the fifth largest industry in the country. At the time, most buildings were lit with whale oil, but increasing scarcity of whales drove up the cost of the resource, spurring competition and innovation. Within a decade of peak oil prices, whale oils lost two-thirds of their total market share.

“Whalers ran out of customers well before they ran out of whales, even before Edwin Drake struck oil in 1859 in Pennsylvania and made kerosene ubiquitous,” he remarked. “Whalers in the late 1850s were begging for federal subsidies on national security grounds.”

“Whales were saved by technology and profit-maximizing capitalists.”

Jumping forward to today, Lovins said the United States can eliminate its imports of oil while revitalizing its economy without taxation or new federal regulation.

“Unlike other proposals to force oil savings through government policy, our proposed transition beyond oil is led by business for profit,” he said. “We’re not counting on regulations to make markets. Instead markets will drive innovation.”

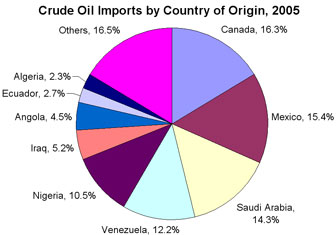

Referencing Winning the Oil Endgame: Innovation for Profits, Jobs, and Security, a joint study by RMI and the Pentagon published in 2004. Lovins said that investing $180 billion over the next decade to eliminate oil dependence and revitalize strategic industries can save $130 billion gross, or $70 billion net, every year by 2025 (assuming oil is $26 per barrel, higher oil prices mean higher savings). At the same time, the efforts would make American industry more competitive, improve national security, cut carbon dioxide emissions by 26 percent, and save a million transportation jobs now at risk, while creating one million net new jobs. Under the blueprint, by 2015 the U.S. could eliminate its imports from the Persian Gulf; by 2040, oil imports could vanish all together; and by 2050, the U.S. economy could be oil-free.

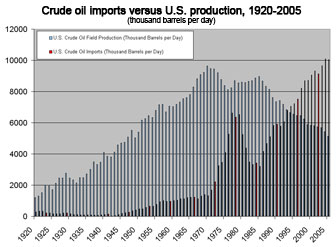

Lovins said equivalent transformations have occurred in the past, noting that when the U.S. last paid attention to oil, in 1977—85, it cut its oil use 17%, oil imports 50%, and Persian Gulf imports 87% while the economy grew 27%. He said that eight year period showed that customers had more power than OPEC. RMI’s bold forecasts assume a slower pace of transformation than in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Here’s how

Noting that vehicles use 70 percent of oil in the United States, Lovins said some of the biggest savings would come from changes in how cars are designed: making them lighter would reduce oil consumption and make cars safer and more reliable.

Lovins said that the historic efforts to improve gas mileage by focusing on the engine was the wrong place to start. Observing that three-fourths of fuel use is weight-related and that only 0.3 percent of fuel burned goes toward accelerating the driver, Lovins argued that large gains will come from reducing energy loss at the wheels where each unit saved translates to 7-8 units of gas. This is best done by managing the weight of the car. “Ultralighting” vehicles using carbon composites or ultralight steels is essentially “free” with cost increases for materials offset by gains in efficiency.

Answering critics that say lighter cars are less safe, Lovins cited studies of nationwide crash data that show vehicle size confers safety — weight does not. Lovins pointed to the immaterial damages caused by a side impact by VW Golf on a SLR McLaren as an example of strength of carbon composite materials which can absorb 6-12 times as much energy per unit as conventional auto body steel. He showed a video of race-car driver Katherine Kegge walking away virtually unharmed after a 290 km/hr crash into a concrete wall. She was in a carbon composite car body.

His remark, “You can see plastics have change since The Graduate,” drew chuckles from the audience.

Lovins said that carbon composites have long been used in aerospace because they’re stronger and tougher than steel but only a quarter as dense. While carbon composites have typically been quite expensive, they don’t have to be, he said, thanks to scaling work done by former Lockheed Martin / Skunk Works engineer David Taggart, who is now CTO of Colorado-based Fiberforge, a closely-held firm developing such materials.

Using these materials, RMI designed a prototype Hypercar, a mid-size SUV that gets 114 miles per gallon-equivalent with a fuel cell but costs only marginally more than the conventional equivalent, a difference that is recouped within two years on energy savings alone. Of these additional costs, only 1.6 percent comes from the expense of ultralighting. From a safety standpoint, Lovins said that industry-standard collision simulations showed that a 35-mph crash into a wall wouldn’t damage the passenger compartment, while in a head-on collision with a steel SUV twice its weight, each vehicle traveling at 30 mph, the carbon-fiber Hypercar would protect its passengers from serious injury.

Not only would the car be more efficient, its manufacturing process would be radically simplified. Its snap-together assembly would dramatically reduce tooling (by 99%) and equipment costs. The plant would have a 40% lower capital cost and be two-thirds smaller than the best plants today. Already, he said, BMW building is carbon fiber cars, while Honda and Toyota are developing carbon fiber airplanes.

While carbon composites are attractive, he said that extra light steel may also be competitive with carbon fiber, but that the market will determine which is better.

“To get the cleanest and most efficient cars, don’t mandate them—just let the customer demand and get superior design,” he said was an appropriate automotive hiyaku to describe the process..

Lovins ran through a series of examples of ultra efficient cars, including the Loremo 2+2 sports car, which when it is released in 2009 will cost 10,990-14,990 Euro ($14,700-$20,000) and get 87 or 157 miles per gallon.

He said the design paradigm also applies to heavy trucks, which are expected to account for 12 percent of all U.S. oil in 2025 according to Department of Energy estimates. Carbon fiber manufacturing could double the margins of big haulers from 3% to 6-7% and cut total heavy truck oil consumption by two-thirds by 2025. He said the profit motive is already driving the transition. Public transportation, from buses to trains, would also gain from improved efficiencies.

Lovins said that any vehicle — whether gas powered, plug-in hybrid, or electric — can be improved by making it lighter.

He highlighted plugin hybrids. Acknowledging that cars are park 96 percent of the time, Lovins pointed out the benefits of charging vehicles with cheap off-peak (night-time) electricity and selling valuable power storage at peak hours back to the grid, a transfer that could pay for the additional cost of batteries. He estimated that a large fleet of plugins could have the capacity to displace electricity generated from new coals and nuclear plants with 6-12 times total U.S. electric generating capacity.

Saving American Automakers

Lovins said the first automaker to develop an ultralight car will win the fuel cell race, which will dramatically increase vehicle energy efficiency and performance. He said the new design offers the best hope for Detroit to recapture its past market dominance.

He compared the current state of U.S. automakers to Boeing in 1997. Back then the airplane maker as fast-losing market share to Airbus and its margins were falling. Within a few years, the company reinvented itself with the 787 Dreamliner, an aircraft constructed of carbon composites that is 20 percent more fuel efficient than its predecessors and takes 3 days to assemble rather than 11 days for the 737. It became the fastest-selling plane in the history of the aerospace industry and the plane is sold out until 2013. Meanwhile, the new conventionally designed jumbo jet, the Airbus A320 jetliner, is two years late and over budget.

Looking down the road, Lovins said that the airplane industry believes it can make its fleet two to three times more energy efficient than it is today. There are even suggestions that cryoplanes, planes that use liquefied hydrogen gas fuel and produce no carbon dioxide emissions, could be the aircraft of the future. They are safer and more energy efficient, he claimed.

Lovins sees signs that Detroit is eyeing a Boeing-like turn around — showing interest in light-weight composites and Ford Motor Co. brining on Alan Mulally, a former Boeing executive, now in place as CEO. He added that big changes are happening quickly in the industry.

Lovins said that Detroit should look to the American military for energy efficiency inspiration. Realizing that reliance on long oil supply chains is a major liability in the battlefield, the military is become a leader in developing and using pioneering energy technologies. It also sees the strategic value of becoming less reliant on oil imported from potentially hostile regions.

Biofuels

Lovins said that new biofuel technologies could provide 3.7 million barrels of fuel per day at a cheaper cost than oil without subsidies or crop, land, or water problems. He said the U.S. shouldn’t waste it’s time with corn ethanol, but focus on cellulosic ethanol made from woody grasses like switchgrass that can be grown on marginal lands. He also said that eliminating the 51 cent traffic on imported sugar cane ethanol from Brazil would help reduce or oil needs. He noted that Brazil has replaced 26 percent of its gasoline with sugar-cane based fuel grown on 5 percent of its crop area.

Sweden expects to be independent of oil by 2020 using wood waste for biofuel.

Questions and answers

When asked about Tesla, Lovins said the Silicon Valley-based car startup is a very capable outfit. He believes the firm will demonstrate that if you ge the physics of the car right, you can do better than GM’s EV1, which was the best commercially available electric car to date.

Lovins added that while he thinks battery cars will be big niche, in the long-run batteries will still be limiting factor relative to fuel-powered vehicles. Regardless of what powers the car, however, Lovins reiterated that automakers will do better with light, aerodynamic designs.

To the question, “Should I buy a car now or wait for the next generation?” Lovins responded that if he needed to buy a readily-available car today, he would purchase one of the several hybrids on the market, probably one of the more aerodynamically designed models. He noted that dealers would also like him to buy a hybrid since they have twice the margin on the vehicles.

He added that most people — including Consumer Reports which rates cars — don’t drive their hybrids to maximize fuel economy. He said there are two key elements to driving a hybrid properly, braking and accelerating.

“If you are going to stop, start gently braking early so you generate electricity that is fed back into the battery… Less obvious is that drivers should accelerate briskly up to cruise speed, where the engine runs most efficient at high torque,” he said. “These recommendations are exactly the opposite of Consumer Reports and Driver’s ed classes will tell you.”

Lovins speaks again Thursday and Friday at 7:30 pm at Stanford University. More information is available at http://www.maproyalty.com/Lovins.html

- The Rocky Mountain Institute

- Oil End Game

- Small Is Profitable

- Natural Capitalism

- The Community Energy Opportunity Finder

Recent energy articles appearing on mongabay.com