Ebola outbreaks kill 25% of world’s gorillas

Ebola outbreaks kill 25% of world’s gorillas

Disease hits African parks, $35M could save apes from hemorrhagic fever

mongabay.com

December 7, 2006

The Ebola virus, a nasty hemorrhagic fever that causes massive organ failure and bleeding, is killing thousands of endangered gorillas across Central African forests according to new research published in the journal Science. While the findings suggests that even in strictly protected wildlife sanctuaries gorillas are not safe, the research provides insight on how to control Ebola outbreaks among wild gorillas (Gorilla gorilla) and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes).

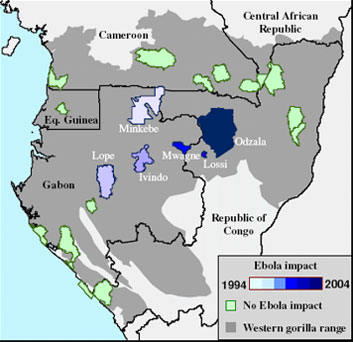

The new study, led by Magdalena Bermejo of the University of Barcelona, provides strong evidence that Ebola killed at least 5,500 at a single site — the western portion of the Lossi Sanctuary in northwest Republic of Congo — in outbreaks between 2001 and 2005. Bermejo, along with José Domingo Rodríguez Teijeiro (University of Barcelona), Carles Vilà (Uppsala University in Sweden), and Peter Walsh (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology) found extraordinarily high rates of ape mortality caused by Ebola outbreaks in 2002 and 2003 in Lossi. Gorillas suffered a 95 percent mortality rate, while chimps had 77 percent mortality rate, according to transect surveys conducted by the researchers. While exact numbers aren’t yet known, the team estimates that Ebola outbreaks over the past twelve years may have killed 25 percent of the world’s gorilla population.

Young gorilla in Gabon.

|

“We don’t have a scientifically rigorous estimate of how many gorillas there are in the world, much less how many have been killed by Ebola,” said Dr. Peter Walsh, a Group Leader in the Department of Primatology of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig Germany. “But based on the proportion of prime gorilla habitat that has been affected and typical Ebola mortality rates, an educated guess is that about 25% of the world gorilla population has been killed by Ebola in the last 12-15 years.”

The researchers say the Ebola outbreaks are particularly troubling because they are occurring in areas set aside for ape conservation.

“The conservation implications are huge because the outbreaks have been concentrated in large, remote protected areas that were supposed to be the stronghold for gorilla and chimpanzee protection,” Walsh told mongabay.com via email. “Ebola is not going to drive gorillas extinct, but it is going to push them onto a slippery slope which it will be difficult to climb back up.”

The researchers say that while Ebola has not totally extirpated apes from Lossi, it has reduced once large populations down to smaller sizes at which they are “significantly less resilient to illegal hunting and other looming threats.”

“Although habitat loss is a huge problem for gorillas and chimpanzees in eastern Africa and chimpanzee populations in west Africa, it is a very distant third to Ebola and bushmeat hunting in western equatorial Africa where these Ebola outbreaks have been occurring,” Walsh told mongabay.com. “Confinement to small populations has not played a role in these outbreaks. To the contrary, these outbreaks have been in really large, high density populations. Thus, the story is really that it is Ebola which is reducing western gorillas to small populations (not habitat loss), at which time they then become more susceptible to factors such as hunting.”

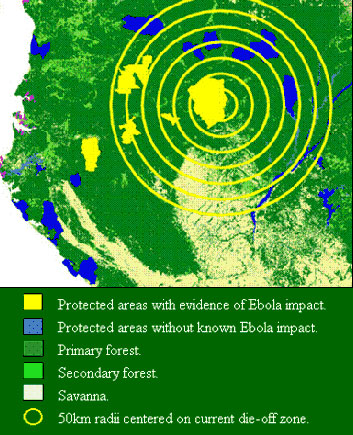

There is also concern that Ebola appears to be spreading towards other protected areas in the region, but team notes that a vaccination campaign could reduce the impact of Ebola in these yet affected gorilla populations. Since the disease appears to be spread from gorilla social group to gorilla social group, and not from a reservoir host, targeted vaccination could break the chain of transmission. Further, because the research suggests that Ebola is progressing at a consistent state, a vaccination campaign could be “targeted just ahead of the advancing wave.”

“The current lack of a vaccination program is not due to a lack of vaccine options, as several different vaccines have now protected laboratory monkeys from Ebola and major vaccine labs are anxious to help,” write the researchers in a news release. “Rather,” said Walsh, “Uncertainty about whether a large Ebola control effort was necessary or even possible has paralyzed large donors and major conservation organizations. We are hoping that the starkness of our results will push some public or private donor to finally commit the two or three million dollars necessary to develop a safe and effective way of delivering Ebola vaccine to wild apes.”

“The really depressing part is that, from a technical standpoint, vaccination is very doable,” lamented Walsh. “The remaining technical hurdles are not trivial, but they are much lower than those already jumped. What is holding us back is not technical capacity but rather a failure of imagination and of will.”

Walsh says that the initial costs of a vaccination campaign scare off conservation groups.

“People in the conservation community are intimidated by the up-front costs of vaccination and would prefer to instead spend the money on anti-poaching. What they are not factoring in is the fact that one year of Ebola vaccination could save as many apes as decades of anti-poaching. We need to do both.”

Protected areas with important western gorilla populations. Courtesy of Dr. Walsh

|

“In the big picture, the costs involved in mounting an Ebola control program for apes are trivial: perhaps $2-3 million to do lab tests on safety and efficacy and field studies on vaccine delivery, with the costs of full implementation depending on what delivery method (dart or bait) was used and how many animals were vaccinated,” he added. “To put things in perspective, the US government is spending $35 million on a retirement home for 200 laboratory chimpanzees. $35 million would not only vaccinate many thousands of wild apes it would also pay for decades of anti-poaching.”

Walsh further notes that Ebola has set back ecotourism development — an important potential source of revenue for Republic of Congo — by frightening away investors and ecotourists as well as killing gorillas in Odzala National Park and Lossi.

“The real tragedy is that a relatively small amount of money, a few million dollars, could make a huge difference,” Walsh said. “If we don’t spend it now, we will have to spend ten times as much to intensively manage the small remnant populations in the future. Why do we always wait until it is too late?”

“When people look back 100 years from now, most won’t even remember Iraq. One thing they will remember is that we sat by and did nothing while our closest relatives slipped away. This is a case where one wealthy individual could have an enormous impact. He or she could quite literally save gorillas from ecological extinction.”