Villagers in the country’s lush Black Sea region face police force, legal hurdles, and more subtle means of suppression in their fight to protect the environment.

The Fol Creek Valley outside of Trabzon, Turkey. Residents are fighting plans to build a cement factory, several rock quarries, a gold mine, and three hydropower plants in the area. Photo: Jennifer Hattam.

The Fol Creek Valley outside of Trabzon, Turkey. Residents are fighting plans to build a cement factory, several rock quarries, a gold mine, and three hydropower plants in the area. Photo: Jennifer Hattam.

The Fol Creek Valley rises steeply from Turkey’s Black Sea shoreline, the grey concrete of the coastal cities quickly giving way to lush green hills dotted with homes, barns, and the occasional twin spires of a small mosque. In the summer months, villagers here lead their livestock up through the pine-forest-covered mountains to graze in the yayla, or highland pastures.

“The cows here graze on 400 different types of plants, which gives the butter made from their milk a special taste and aroma. Even people in Istanbul seek it out,” Pekir Uzun told mongabay.com. A spokesman for the Tonya Environmental Platform, Uzun works as a furniture maker in the valley’s largest town, Tonya, home to about 7,000 people in addition to the 8,000 or so living in the surrounding rural villages.

In February, 250 of these residents joined counterparts from around the Black Sea to march the 800 kilometers (500 miles) to the Turkish capital city of Ankara to protest environmentally damaging development in the region. In the Tonya area, this includes plans to build a cement factory, several rock quarries, a gold mine, and three hydropower plants.

“We don’t want to have the pollution of industry here; we want to keep this rich nature and leave it to our children,” said Uzun.

Over the past two decades, industry has encroached rapidly on Turkey’s Black Sea region, a little-visited part of the country that stretches some 1,300 kilometers (800 miles) from the Georgian border almost all the way to Istanbul. Home to just 10 percent of Turkey’s population of 75 million, it contains some of the country’s most beautiful and biodiverse natural areas. As the threats to these places multiply, so too has the local resistance. But protests like those held in Tonya can be fraught with peril.

In May 2012, residents of Köknar and Karaçam villages in the Solaklı Valley, about 100 kilometers (60 miles) east of Tonya, sought to stop construction of one of the more than 30 hydropower projects planned for their small valley. Villagers who tried to block the road to the planned power-plant site came face to face not only with the construction company’s bulldozers, but with a full battalion of Turkey’s paramilitary rural police.

“The state brought in 600 gendarmes on behalf of the company — one for every man, woman, and child protesting,” İhsan Bektaş told mongabay.com. Bektaş represents the Brotherhood of the Rivers activist group in Trabzon, the province that includes both Tonya and the Solaklı Valley. Villagers were tear-gassed. Dozens were detained by police and charged with blocking the road and other offenses that can carry jail time and fines of up to $3,000 — about eight times the monthly minimum wage.

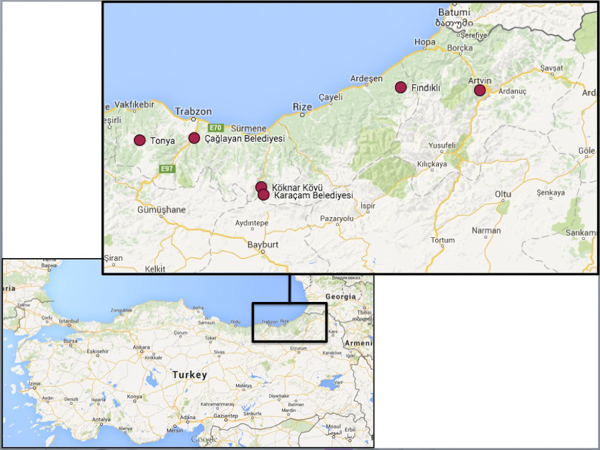

Map of Turkey. Map credit: Google Maps. Click to enlarge.

This April, a public prosecutor opened a case against 56 villagers in Zile, a Black Sea town further inland from the coast. The villagers, whose protests in March against hydropower projects were likewise met with tear gas from gendarmerie forces, face multiple charges, including “resisting public servants,” “insulting,” and “violating the law on demonstrations.”

“If people take to the streets, they risk having cases opened against them by the government, and by the companies, who can sue them for damages,” Alp Tekin Ocak, an Istanbul-based attorney who does pro bono work representing Black Sea villagers fighting environmental threats, told mongabay.com. “People don’t usually end up losing these cases, but they add to the pressure [to keep quiet],” Ocak said.

Many people fear that the risks of protesting in Turkey are becoming even greater. In late March, parliament passed a new internal security law that Amnesty International warned “will give police wide-ranging powers to repress dissent,” including broader authority to detain protesters and use force against them.

“Making it easier for the police to be more violent, to come into people’s homes without a court order and detain them is likely going to mean fewer people are willing to protest,” Ocak’s law partner, Murat Deha Boduroğlu, told mongabay.com.

Suppression of protest in Turkey happens in more subtle ways as well. People around the Black Sea region talked about how local elected officials, or the state-employed imam at the local mosque, would encourage residents not to oppose the construction of power plants, mines, and other projects.

In the eastern mountain town of Artvin, activists said the local governorate, which owns the area’s only large meeting room, has stopped allowing anti-mining groups to rent the space out for panel discussions and press conferences. People who speak out or demonstrate against industrial development are often maligned by public officials and the country’s pro-government press as “marginal” elements in society, “provocateurs,” even “terrorists.”

Turkey’s governing Justice and Development Party (AKP), in power since 2002, lost its parliamentary majority in elections held 7 June. The coming months are expected to bring either the formation of a coalition government, or a call for a new election; whether restrictions on free expression when it comes to environmental and social issues will be tightened or loosened remains unclear.

For now, though, the legal and regulatory system in Turkey often seems stacked against environmentalists. “The laws are changing very quickly, and it’s expensive for a citizen to open a case [against a development project],” said Bedrettin Kalan, a lawyer and activist with the Green Artvin Association. One 70-year-old farmer in the Black Sea region has become something of a local hero for selling his cow to pay his legal fees. And even victory requires constant vigilance to maintain.

“If citizens win in court, the company can change a few lines in their environmental impact assessment and start the process all over again,” said Kalan.

A traditional stone-and-timber house and tiers of tea bushes in the Çağlayan Valley, where eight hydropower projects are planned. Photo: Jennifer Hattam

People around the Black Sea town of Fındıklı have been fighting for nearly a decade to keep hydropower development out of their valleys, thus far blocking each of two dozen planned projects in turn. With most of the region’s biggest rivers already damned, the hydro projects planned for Fındıklı, Tonya, and elsewhere around the Black Sea are generally smaller-scale investments that reroute part of a river into a tunnel or pipeline rather than blocking the whole river and filling up a large reservoir. Planned properly, these “run-of-the-river” projects are often considered to be more environmentally friendly than large dams, but when constructed one after another on the same river, as they frequently are in Turkey, even small hydro can have a devastating impact.

“Everything here depends on our rivers: our hazelnut and tea harvests, the fruits and vegetables we grow to feed ourselves, the cows we keep to make yogurt, cheese, and butter,” said Seniye Özkaya, a teacher who lives in the Fındıklı area’s Çağlayan Valley, where eight hydropower projects are planned.

Hazelnut trees grow thick along both sides of the small road leading into the valley; the villagers harvest them each August by shaking the trees and gathering up what falls. Traditional stone-and-timber houses sit at the base of the hills, below tiered rows of tea bushes. In the center of Çağlayan Village, population 500, an Ottoman-era stone bridge still arches across the crystal-clear river, providing shade for a lone fisherman on its bank.

“Right now, everything is quiet, but for sure it’s not over,” Özkaya said. “So far they haven’t been able to put any projects here. God willing, they won’t ever be able to.”

Other Special Reporting Initiatives Articles by Jennifer Hattam

New solidarity in struggle to protect Turkey’s ‘life spaces’