- State legislators presented the proposal early last month to President Michel Temer’s Chief of Staff, which included changes to five protected areas in the southern state of Amazonas.

- When presenting the proposal, the legislators argued that the “protected” classification undermines the legal security of rural producers and economic investments that have already been made in the region.

- Conservation groups worry that, if approved, the bid would put more than a million hectares of rainforest at risk to deforestation.

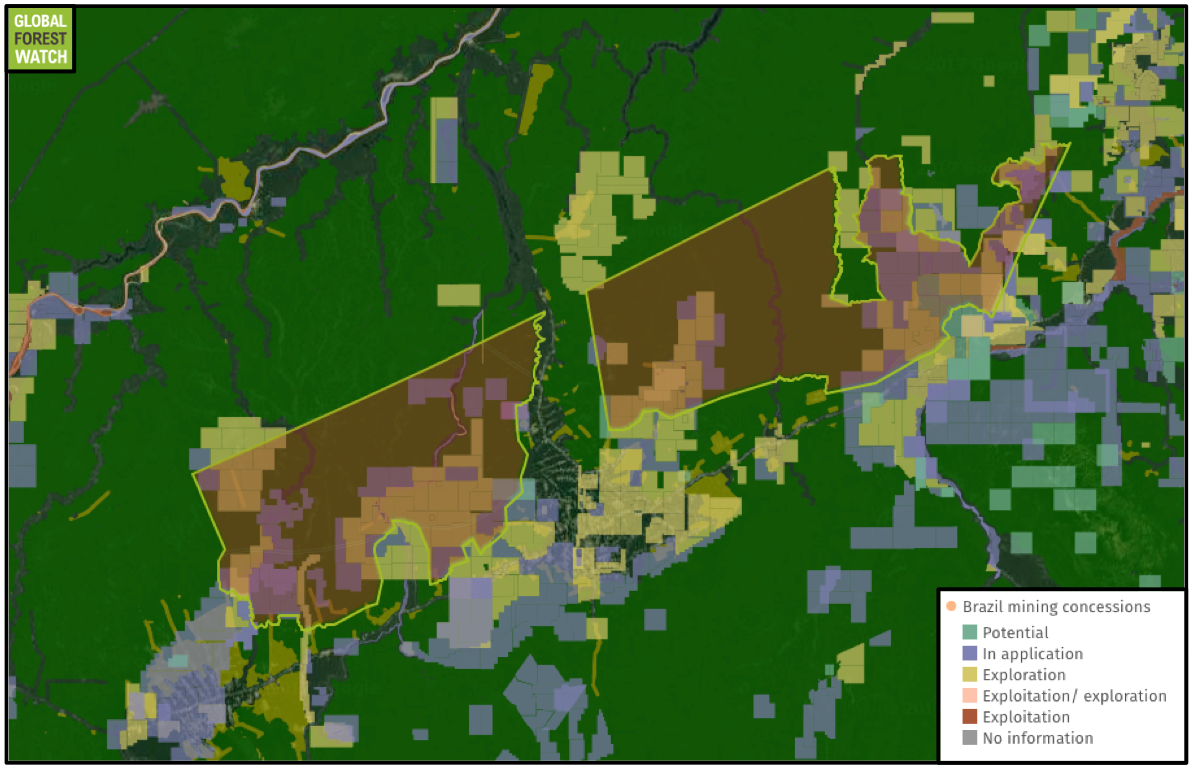

- When surveying documents filed with Brazil’s National Department of Mineral Production, WWF reportedly uncovered a link between the proposed bill and applications for prospecting and mining in southern Amazonas.

A proposal under review by the Brazilian government aims to shrink four protected areas in the Amazon and eliminate another area entirely, Greenpeace says. If approved, the bid would put more than a million hectares of rainforest at risk to deforestation.

“Removing protection from these areas will lead to more deforestation,” Cristiane Mazzetti, a campaigner with Greenpeace Brazil, told Mongabay. “This moves us in the opposite direction of where we need to go now that deforestation rates are once again out of control.”

Indeed, 2016 marked the highest rate of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon since 2008, contrasting the country’s much-heralded efforts to curtail forest loss just a few years back.

State legislators presented the proposal early last month to President Michel Temer’s Chief of Staff, which included changes to five protected areas in the southern state of Amazonas. Among them is the complete removal of the Campos de Manicoré Environmental Conservation Area and a 40 percent reduction in the area of four other reserves: Acari National Park, Manicoré Biological Reserve, and Aripuanã and Urupadi National Forests. If ratified on the senate floor, the proposed bill would shrink protected Amazon forest by more than a million hectares – an area well over the size of Delaware.

The bid comes less than a year after the five areas were officially gazetted by former president Dilma Rousseff under a program called “Terra Legal,” the non-profit Observatorio do Clima reports. By legalizing use of vacant public land, Terra Legal aims to reduce illegal occupation and land-grabbing – two common drivers of deforestation in Amazonas. Protected areas, also known as “conservation units,” are but one of many classifications under the program, which include urban expansion, settlements, and indigenous lands.

But there’s a flip-side to protection, Amazonas state legislators say. When presenting the proposal, the legislators argued that the “protected” classification undermines the legal security of rural producers and economic investments that have already been made in the region.

“The conservation units are hampering the expansion of economic activities, Senator Omar Aziz said, according to a translated press release from the Ministry of the Environment. “And its creation created very serious legal insecurity throughout the southern state.”

In a comment on Facebook, Deputy Átila Lins, an official who spearheaded the effort, added that populations are “on the verge of being withdrawn” from the protected areas and indicated that “large investments” have been made in the region. Those investments would be lost, he said.

But exactly which “populations” and what “investments” are impacted aren’t clear from the legislators’ rhetoric – or from the 20-page proposal itself.

In search of answers that might reveal the underlying motivations to reduce the protected areas, environmental groups did their own research – albeit unconventional.

Greenpeace took to the skies. Aboard a small plane cruising over the five protected areas, Greenpeace looked for signs of human occupation and economic activities that might validate the legislators’ claims.

“They said that investments were already made in those protected areas, producers would be impacted, and people would have to be removed, so we decided to fly over those areas to see if what the legislators was claiming was true,” Mazzetti said.

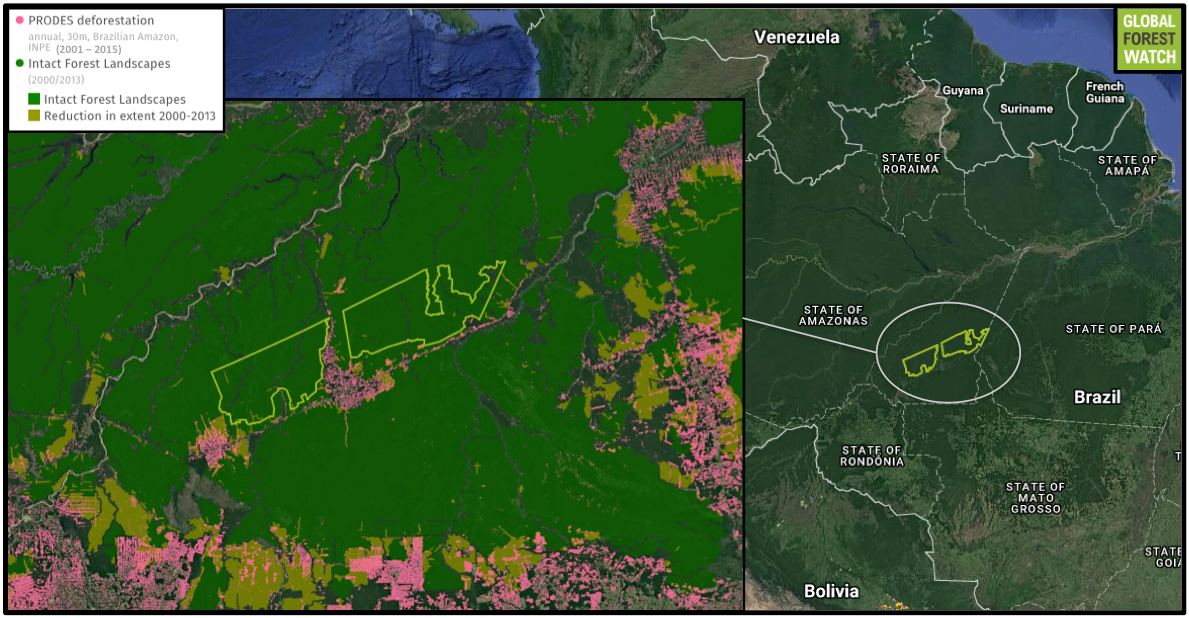

They saw few signs of occupation. What they saw plenty of was forest – large, intact tracts of jungle, for which the state is famous.

“What we saw was a few spots of human activity but the majority of the areas are still preserved,” Mazzetti said. “These lands are far from infrastructure.”

Mazzetti argues instead that the proposal is about making these protected lands viable for economic expansion. And that argument is supported by new research by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).”

That’s where research by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) comes in.

By surveying documents filed with Brazil’s National Department of Mineral Production, WWF reportedly uncovered a link between the proposed bill and applications for prospecting and mining in southern Amazonas. In fact, most of the requests overlap precisely with the areas that may soon lose their protection status, WWF says.

“We noticed that the majority of those exploitation requests are within the limits of the Conservation Units that the new bill wants to cut,” Mariana Ferreira, the science coordinator for WWF-Brazil, told the Thompson Reuters Foundation back in February.

In Acari National Park alone, about 40 requests for prospecting or mining minerals have been filed – some of which have already been authorized, WWF writes.

Environmental groups are concerned – 21 of them to be exact.

“We understand that the maintenance of these protected areas as originally established is crucial for the conservation of regional biodiversity,” they wrote in a letter (translated here) to President Temer and several other senior officials, which 21 organizations signed, including The Nature Conservancy, Wildlife Conservation Society, and Conservation International. “Removing the protection of one million hectares will contribute to the – already remarkable – deforestation in the Amazon.”

The move could also “jeopardize” commitments under national and international accords, such as the 2015 Paris Agreement, which entered into effect last November, they said. Indeed, research suggests that protected areas may store large carbon stocks, and deforestation already accounts for 40 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in Brazil.

The bid might put international financing at risk as well, Mazzetti says.

“It will affect the country’s international credibility and the investments that international financiers are promising to make,” she said. “Donors might start questioning how effective the money is that they’ve invested in Brazil.”

Germany, one of the Brazilian Amazon’s biggest donors, invested over $100 million in the Protected Areas of the Amazon Program – the very initiative that helped put these five areas in place. Norway has also dished up substantial sums of money.

Brazil’s Ministry of the Environment declined multiple requests for comment. But earlier this week, the Minister of the Environment Sarney Filho announced that a committee – including researchers from the Ministry, businessmen, and politicians – would be reviewing the proposal and visiting the protected areas in question. At a meeting in Brasilia, Filho expressed that he’s open to dialogue, but noted that there are “conflicting points” between the proposal and the Ministry’s official data.

“It is fundamental to resolve doubts about the existence of settlements within these areas and other types of economic activities,” the minister said in a translated statement. “We have no prejudice against proposals, but in this case it is necessary to clarify the doubts that have been raised.”

The minister also highlighted that these five areas protect a region facing heightened pressure from deforestation. From 2015 to 2016, forest loss in Amazonas increased by 54 percent, according to the National Institute for Space Research of Brazil – much of which was concentrated in the region where these areas lie, called the “Arc of Deforestation.”

Filho’s statements come just weeks after the Ministry announced that a priority of 2017 is to expand Brazil’s protected area network, which currently includes 327 federal areas. But if the proposal becomes a bill, it will likely pass on the senate floor, Mazzetti says – rolling that number back to 326.

“It’s very likely that if it goes to congress it will be passed – these projects usually get approved,” she said. “We know that congress has lots of representatives of the business lobby, and for them it’s important to open new areas.”

But before it becomes a bill, environmental groups have more leverage, she adds.

“If we apply pressure [now], I believe we can stop it,” she said. “Our plan is to try to stop this from the very beginning.”