Animal vehicle collisions (AVCs) take an incredible toll on wildlife worldwide. In the United States, for example, as many as 1.5 million deer, moose, and other ungulates are annually involved in vehicle crashes, with all yearly U.S. wildlife collisions costing $1 billion and causing 29,000 human injuries. Still, drivers and the media tend to downplay these costs to world wildlife and automotive safety.

Now researchers from America and Africa have taken a serious statistical look at driver attitudes as a means of avoiding AVCs, and the results have just been published on mongabay.com’s open-access journal Tropical Conservation Science. Knowing how people drive and their feelings toward animals is important to determining how AVCs happen, and how they can be prevented.

The study was done in the Tarangire-Manyara-Ecosystem of Tanzania, an area of savannah grassland with high biodiversity and three protected wildlife areas, including the 2,850 square kilometer (1,100 square mile) Tarangire National Park. Significant numbers of collisions occur in the region with its 350 bird, 290 reptile, 40 amphibian, and 35 large mammal species. The scientists note that there have been “few attempts to reconcile [transportation] infrastructure development with wildlife conservation in the tropics,” and see their research as a step in that direction.

Elephant crossing Karatu-Makuyuni road into Lake Manyara National Park. Photo credit: John Kioko.

Elephant crossing Karatu-Makuyuni road into Lake Manyara National Park. Photo credit: John Kioko.

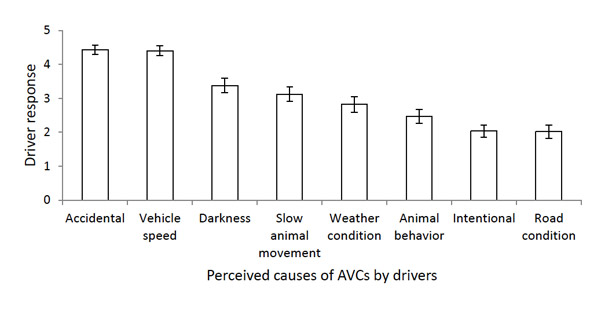

More than 60 area drivers who had experienced AVCs during the 18-day study period, were given questionnaires asking them to rate the primary cause for their crashes. Their choices were: accidental, speed, darkness, bad weather, animal behavior, and intentional. Of the driver’s interviewed, 98 percent were male, with ages ranging from 22-58, and varying levels of education. Those questioned had vast differences in driving experience in terms of years. The study was conducted on two roads totaling 75 kilometers (46.6 miles), with speed limits ranging from 30-100 kilometers (18.6 – 62.1 miles) per hour.

According to the study, high vehicle speeds and accidental killing were the main AVC causes admitted to by drivers. The lowest rated causes were intentional killings and road conditions; one factor not taken into consideration was the possible consumption of alcohol by drivers.

Of all the types of animals monitored, birds were hit the most (49 percent), followed by mammals (23 percent), reptiles (18 percent), and amphibians (9 percent).

Despite the fact that nearly 50 percent of observed collisions were with birds, drivers perceived otherwise, believing that mammals were hit more often than any other animal. “[D]rivers believed mammals to be the most impacted by AVCs (74%), followed by reptiles (12%), birds (8%), and amphibians (7%),” says the study. This large discrepancy between reality and perception may result due to the lesser damage done to vehicles by smaller animals, or possibly because drivers have greater concern for larger animals, note the scientists.

The majority of drivers said that they tried to avoid hitting an animal whenever possible, particularly large mammals who they perceived could do damage to them or their vehicle. “Drivers reported that they did everything possible to avoid hitting an elephant. Domestic dogs were reportedly most likely to be hit by vehicles, followed by frogs, birds and snakes. When asked how they would react (swerve, stop, or slowdown) to avoid an AVC, most drivers said they would swerve in case of snakes, tortoises/terrapins, and frogs. Drivers said that they were least likely to swerve in case of birds and would instead hit them.” The study also found that “most drivers (80 percent) felt that other drivers respected the wildlife crossing the road.”

Response rating of (5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = neutral, 2 = disagree, 1 = strongly disagree) driver views on the causes of animal vehicle collisions (±SE). Photo credit: John Kioko.

While the drivers questioned generally felt they respected wildlife and took precautions not to hit animals, a large proportion (65 percent) have never taken a driver education course or awareness program on the effects of collisions on wildlife. The authors observed that driver responses had no relation to the number of years interviewees had been driving, but coincided better with education level.

It was suggested by 37 percent of drivers themselves that a general safe driving course could help lower AVC incidents; 22 percent of drivers suggested that the use of road signs would cut AVCs; while 20 percent recommended policy and regulation changes; 14 percent suggested changing speed limits; 5 percent of drivers recommended improved courtesy, and 2 percent called for improved road conditions.

The researchers put driver education first: “[M]ost drivers were indifferent to whether AVCs were considered problematic,” says the study. “Instilling consideration, care and empathy for all wildlife should form a focus of AVC mitigation forums. To that end, directed education can promote safe driving habits on the roads.”

The researchers also say that placing road signs is the second best way to reduce wildlife collisions: “[F]lexible signposting during peak migration times may increase driver attention. For example, signs could be an effective mitigation strategy on some of the road sections which are critical movement points for animals such as African elephants,” say the researchers.

The scientists hope that local authorities will use the study data to improve driver awareness toward wildlife and reduce collisions. They say that the best way to gauge the effectiveness of any wildlife awareness campaign is to set up long-term wildlife roadkill monitoring programs.

Citation:

- Kioko, J., Kiffner, C., Phillips, P., Patterson-Abrolat, C., Collinson, W., & Katers, S. (2015) Driver knowledge and attitudes on animal vehicle collisions in Northern Tanzania. Tropical Conservation Science Vol.8 (2): 352-366.