Oceans not only provide important ecosystem services, including climate regulation and nutrient cycling, but they also serve as a major contributor to food and jobs. Yet human actions in the oceans are having a major impact on species, sometimes in unexpected ways. Indeed, a recent study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B finds that bottom trawling may be making some fish skinnier.

Investigating how trawling affects the prey and diet composition of two flatfish species, plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) and dab (Limanda limanda), Andrew Frederick Johnson, found that bottom trawling leaves plaice with reduced biomass. In other words, the fishing technique could be responsible for skinnier plaice.

Johnson, a postdoctoral researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography’s Center for Marine Biodiversity & Conservation and lead author of the study, conducted his study along a gradient of commercial bottom trawling in the northeastern Irish Sea. Chronic trawling here primarily targets Norway lobster (Nephrops norvegicus), but it is clearly impacting non-target species as well.

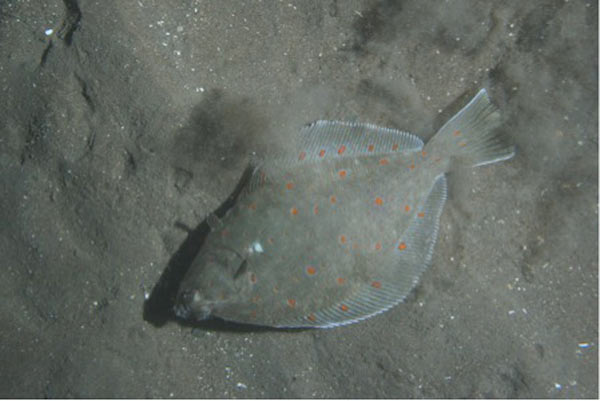

Plaice (Pleuronectes platessa), a commercially important flatfish species. Photo by: Andrew Johnson

“Trawling is non-selective. Whatever gets in the way of the trawl net, whether it be sessile or…mobile (and in the case of fishes, those [that] cannot out-swim the gear) is caught,” Johnson told mongabay.com.

The Anatomy of a Trawl Fishery

Trawling refers to a common commercial fishing technique in which boats drag ropes and chains across the ocean floor, flushing bottom-dwelling fish and invertebrates into nets.

Fishing trawler preparing nets in the northeastern Irish Sea. Photo by: Andrew Johnson

Fishing trawler preparing nets in the northeastern Irish Sea. Photo by: Andrew Johnson

While trawling has certainly proven effective in capturing large quantities of commercially desirable fishes and crustaceans, this method also poses a high risk to overall benthic, or sea floor, diversity and abundance. Trawling can reduce the complexity of seafloor ecosystems, as well as decrease the size and biomass of the creatures that inhabit them. Moreover, the impacts of trawling spillover into other places.

“These impacts are not limited to a certain area; they are ubiquitous. Wherever trawling occurs, these effects will occur, albeit at a range of different magnitudes,” Johnson explained.

In general, an ecosystem with a low level of natural bottom disturbance will be more vulnerable to trawling damage. An ecosystem already experiencing high levels of natural disturbance—such as wave energy—- and low complexity–a flat habitat, for example–will not be as impacted. By focusing on deep-sea habitats, the current expansion of trawling fisheries poses a significant threat to marine life. These waters have low natural levels of disturbance, so trawling does massive damage.

“Skinny” plaice

While it may be tempting to conclude that lean fishes are simply a result of reduced food availability, Johnson reveals that this is not the case. In areas of high trawling frequency, the study found that fish and prey biomass decreased concurrently, leaving the same fish to prey ratio the same as before trawling occurred. Instead, the fish may be skinnier due to subtle changes in the way they feed.

For this reason, Johnson took into consideration the entire food web, including the status of invertebrate species serving as prey for plaice and dab.

“[Our] finding highlights the importance of really understanding trophic interactions and food webs in depth [by] looking at where energy is transferred and who feeds on who,” he said. “If we don’t know this sort of information we will always be playing a guessing game and may be missing the subtle consequences of human impacts on ecosystems. In order to manage any system effectively and precisely, it is essential that we know the system as best we can.”

Despite the altered quantity and composition of food supply due to trawling, plaice and dab maintained normal levels of stomach fullness and gut energy content. This leads Johnson to believe that increased foraging may be at least partially responsible for the reduction in body condition

Whereas dab possess a broad diet, plaice have a more specialized feeding strategy, perhaps requiring additional foraging time.

“In areas of high trawling, it appears that plaice is stuck [as a specialist] feeding on low quality prey, whereas, importantly, species like dab can alter what they eat and they can still maintain an [energy-rich] diet,” Johnson noted.

In contrast, the study found that dab was not negatively impacted by trawling, given that the species had higher levels of stomach fullness and stomach energy content than that of plaice.

Although the study examined diet, rather than behavior, “it [seems], that in areas of high trawling, the plaice are unable to make [substantial] enough changes in their diet to satisfy their energetic requirements,” Johnson told mongabay.com.

Johnson further noted that plaice, as specialists, forage less efficiently for low energy prey, making them more vulnerable than generalists like dab.

“We find skinny plaice because of their specialist diet and inability to change what they feed on. This ultimately means that…predators get a skinnier meal,” he said.

And those predators are largely human.

Lean fish are less valuable

Not surprisingly, fishers tend to favor “fatter” fish, particularly in a quota-based system. And, since, as Johnson points out “a skinnier fish is a less valuable fish to a fisher,” it may be that they throw away more skinny fish due to their low market value. Such a practice could result in increased plaice removal in fishing areas less visited by trawlers and, consequently, more severe impacts to benthic habitat.

The feedback loop described by Johnson clearly presents economic effects for those in the fishing industry. Fishers are forced to seek out less desirable harvesting locations and are complicit, by necessity, in furthering the depletion of their livelihood.

Johnson urges the general public to remember our deep dependence on the ocean and its productivity.

“If we continue to fish at unsustainable levels, whether this be [in terms of] taking too many fish or damaging too much marine habitat, the ramifications are going to be an altered system which has a lower production of marine products which we eat and rely on for protein.”

Does trawling belong in Sustainable Fisheries?

The negative impacts of bottom trawling on the benthic community lead to a question: should sustainable and integrated fisheries include trawling?

“At present it is impossible to just say ‘yes; trawling is unsustainable; let’s get rid of it,’ as so many people rely on it both for food and employment,” Johnson said.

A fisherman awaits his catch off of the Cumbrian coast. Photo by: Andrew Johnson |

Instead, he advised the reduction of trawling in areas of low natural disturbance—areas where trawling does the greatest damage. Complementary solutions could include the creation of special trawling lanes or the adoption of electric trawls that do not require the disturbance of the ocean floor.

Still, Johnson criticized large-scale trawler operations, especially those that employ few people in relation to the amount of catch they bring in.

“Trawling has to be small-scale [with] small boats employing decent numbers of crew,” he said. “To begin with we need to put a restriction on new boat builds and try to share fishing effort, catch, and quotas to favor smaller, more sustainable practices. It will be a game of weighing environmental sustainability versus economic sustainability.”

Despite active efforts to prevent the rapid expansion of bottom-trawl fisheries, it is expected that more ocean habitat will shift from natural functioning to an altered state due to such large-scale disturbance. Considering that plaice and dab are not target species in this fishery, they may, counter-intuitively, be in greater danger, as their populations are not monitored.

Johnson hopes that stakeholders will bear in mind the concept of baselines.

“An improvement on ten years ago may seem good, but if we compare an improvement today to 100 years ago the comparison changes dramatically,” he pointed out. “It’s important to have perspective—long term—looking back and forward. We need to implement plans now that will have benefits long into the future…i.e. don’t increase a quota just because it will mean more catch next year—what about in ten or 100 years time?”

Citations:

- Johnson A.F., G. Gorelli, S. R. Jenkins, J. G. Hiddink, and H. Hinz. 2015. Effects of bottom trawling on fish foraging and feeding. Proc. R. Soc. B. 282: 20142336