Local farmer in Indonesian New Guinea

Countries poised to receive World Bank funds for achieving reductions in deforestation have insufficient safeguards for ensuring that local communities don’t lose out in the rush to score money from the forest carbon market, argues a new report published by the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI).

The report, released last week, says that without laws defining who has what rights to forest carbon, the influx of money via the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) could increase land-grabbing, jeopardizing livelihoods of local communities and potentially further marginalizing already underserved groups.

“For centuries, governments have been handing out Indigenous Peoples’ forests to supply the next commodity boom—whether rubber, oil palm, cattle or soy,” said Andy White, coordinator of the Rights and Resources Initiative. “The carbon market is the next global commodity from tropical forests and, once again, there is a major risk that Indigenous Peoples are not recognized as the owners of the forest. The World Bank sets the investment standards that many national governments and private companies follow. They are now proposing to weaken their own safeguards and are encouraging governments to sell carbon rights without first ensuring human rights. This puts at risk both the forests and the credibility of the carbon market.”

“On its current path, carbon trading will allow governments to make the decisions, and control the proceeds of the market, undermining local peoples’ rights, and putting at risk the protection of the forest itself,” added Joji Cariño, director of Forest Peoples Programme, in a press statement. “Indigenous Peoples and local communities, who have been stewards of the land for generations, are likely to be further marginalized and dispossessed. Stronger leadership is needed by the World Bank to respect local rights and help governments direct benefits to support local forest owners.”

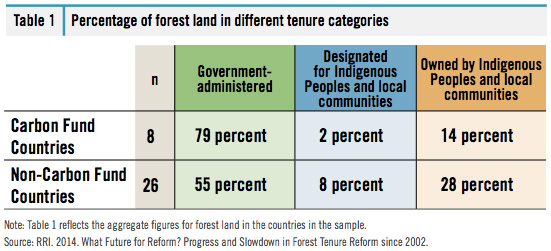

The report, based on analysis of legal systems in eight of 11 countries the World Bank has declared “ready” to sell forest carbon credits, says that models for recognizing and securing land indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ land rights already exist.

“Mexico respects indigenous land rights and has established national funds to compensate forest communities for their carbon, as has Costa Rica,” stated RRI. “El Salvador is planning such a system as well.”

For example, in Mexico, the government controls only 4 percent of the country’s forests while indigenous peoples and local communities have rights to 70 percent. That is a stark contrast to other FCPF countries like Democratic Republic of the Congo (100 percent of forests ‘owned’ by the government), Republic of the Congo (98 percent), Vietnam (98 percent), Indonesia (96 percent;), Peru (71 percent), and Nepal (68 percent).

That ownership structure allows the government to sell forests for commodity production — whether its palm oil, timber, or carbon credits — irregardless of who actually uses and lives in those forests, argues RRI.

“We’ve got to learn this lesson: you can’t get democracy or development, and you can’t stop deforestation, without respecting citizens’ human rights, including local peoples’ rights to their land and forests,” said White. “Without rights you get the resource curse—whether you are talking about oil palm, forests, mining or carbon.”

CITATION: Rights and Resources Initiative. LOOKING FOR LEADERSHIP: NEW INSPIRATION AND MOMENTUM AMIDST CRISES. January 29, 2015