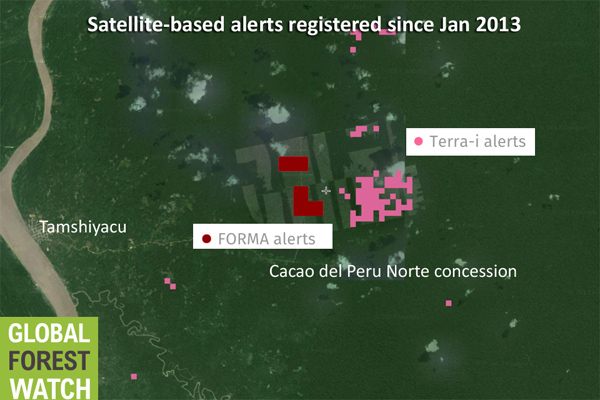

Global Forest Watch image showing recent FORMA and Terra-I forest cover change alerts that reveal clearing in concessions controlled by a subsidiary of United Cacao.

A company aiming to be the world’s largest producer of sustainable cacao, the bean used to make chocolate, appears to have ignored orders from the Peruvian government to cease operations for failing to provide justification for having razed what scientists say was more than 2,000 hectares of old-growth Amazonian rainforest.

The sanctions against United Cacao (LON:CHOC) and its operating subsidiary on a planation near the town of Tamshiyacu came from the Peruvian Ministry of Agriculture on December 9, 2014. The Ministry cited the need to prevent further deforestation and harm to the environment, reports the daily newspaper La Region, based in the region of Loreto where the plantation is located.

The resolution gave Cacao del Peru Norte ninety business days to show what’s called a “classification of land use capability,” to answer questions about whether the land is suitable for large-scale agriculture and to stop all agricultural activities in the meantime. However, it does not appear the company’s leaders are paying any heed.

“As far as we know, workers continue to enter the area to continue their predatory work,” said Professor José Manuyama, member the Committee for the Defense of Water, to La Region. “We condemn the attitude of [Cacao del Peru Norte].”

He urged government officials to enforce the shutdown, and he called for a demonstration in late March to celebrate World Water Day.

Intact forest landscapes in 2000 and 2013 near the United Cacao plantation near Tamshiyacu, Much of the land west of the Maniti River, including the land connected to Plantaciones de Loreto Sur, an oil palm company, showed little to no evidence of human-induced impacts in 2000. The 2013 map shows degradation. Global Forest Watch data still shows large tracts of continuous forest with few signs of human impact.

Based on the company’s own documentation, United Cacao did not perform an environmental impact assessment when it began clearing the land in May 2013, even though a law had been passed by parliament in November 2012 that requires such impact studies prior to land development.

Nor did United Cacao apply for “change-of-use” authorization – also a legal requirement – because the company’s directors contend that they were continuing to use the land for agriculture, although more intensive than in the past.

In another article, Gremish Ahu Yumbato, the secretary of the Patriotic Front political party in the district where Tamshiyacu lies, said La Region that the deforestation has led to more sediment in the area’s streams and rivers, contaminating local water sources and making fishing difficult.

Despite these immediate impacts and ensuing complaints to the Ministry of Agriculture, Ahu Yumbato said he wasn’t surprised that the company has not been forced to stop its work. “All of us here have observed that work continues,” he said. “Nobody has paralyzed anything.”

Further investigation by La Region revealed that enforcement would be up to the Management of Forest Resources and Wildlife Regional Program, according to Mirella Pretell, a representative of the Ministry of the Environment’s Agency for Assessment and Environmental Control.

United Cacao has not disputed its continued development of its holdings near Tamshiyacu. In fact, as part of its recent listing as a public company, it has told the press, the public and potential investors that it owns 3,523 hectares of land in this area and hopes to scale up to more than 4,000 hectares by the end of 2015. However, mongabay.com found no mention of the Ministry of Agriculture’s cessation order in the company’s documentation.

In 2013 the Peruvian news website IDL-Reporteros connected United Cacao’s CEO, Dennis Melka, to five companies that La Region says control more than 45,000 hectares of land adjacent to United Cacao’s currently developing plantation near Tamshiyacu. Sidney Novoa of Save America’s Forests and Matt Finer of the Amazon Conservation Association mapped out the locations of the land that each company controlled.

Holdings along Rio Maniti in the Peruvian Amazon allegedly linked to United Cacao’s CEO Dennis Melka.

As of 2012, according to these registration documents, Melka was the sole board member of Plantaciones de Loreto Sur who could represent the company irrespective of the value of the transaction. The other four board members were limited to transactions maxing out at US$10,000 or US$20,000.

Based on information on the holdings of the various companies obtained by La Region and the map provided by Novoa and Finer, Plantaciones de Loreto Sur controlled more than 9,000 hectares of land between the Maniti and Tamshiyacu Rivers as of 2013

United Cacao reported in its stock exchange admission document that it had financial dealings with three of the four other companies with land holdings in the area, most often in the form of loans given or received in amounts up to US$100,000.

What’s particularly disconcerting to scientists is that much of the 45,000 ha of land that abuts the United Cacao plantation and is connected to companies controlled by its CEO, holds primary rainforest. Maps from Global Forest Watch show that these areas are part of intact forest landscapes, defined as “unbroken expanses of natural ecosystems within the zone of forest extent that show no signs of significant human activity and are large enough that all native biodiversity, including viable populations of wide-ranging species, could be maintained.”

United Cacao’s plantation area near Tamshiyacu, Peru

June 2010

March 2013

December 2013

June 2014

June 2014

June 2014

June 2014

Citations:

- Greenpeace, University of Maryland, World Resources Institute and Transparent World. 2014. Intact Forest Landscapes: update and degradation from 2000-2013. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on 12 February 2015. globalforestwatch.org.

- Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland, Google, USGS, and NASA. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on Jan. 28, 2015. www.globalforestwatch.org.

Related articles

| Scientists warn investors on cacao company’s forest destruction in Peru

(02/06/2015) A prominent group of scientists have sounded the alarm over forest clearing by a cacao company in the Peruvian Amazon. |

| Company chops down rainforest to produce ‘sustainable’ chocolate

(01/20/2015) A cacao grower with roots in Southeast Asia’s palm oil industry has set up shop in the Peruvian Amazon. The CEO of United Cacao has told the international press that he wants to change the industry for the better, but a cadre of scientists and conservation groups charge that United Cacao has quietly cut down more than 2,000 hectares of rainforest. |