Last month Sabah set aside an additional 203,000 hectares of protected forest reserves, boosting the Malaysian state’s extent of protected areas to 21 percent of its land mass. But instead of accolades, Sabah forestry leaders were criticized for how they went about securing those reserves: allowing thousands of hectares of deforested land within an officially designated forestry area to be converted for oil palm plantations.

The controversy centers around a massive concession managed by Sabah’s Forestry Department. The million hectare concession, called Yayasan Sabah, was supposed to be managed sustainably upon its founding in 1966, generating money for social services into perpetuity for the people of Sabah. Instead the concession was used as a personal rainy day fund by successive politicians to enrich themselves and prop up their campaigns, leading to severe overharvesting that decimated forests and wrecked timber yields. By the early 1990s it became clear that Yayasan Sabah was on a path toward insolvency.

Protected forest within the Yayasan Sabah concession. Photo by Rhett Butler

Plunging revenue was met with ever more desperate measures, like harvesting steep slopes, expanding the pool of targeted species, and harvesting smaller trees. Then in 1999 the State Government, signed off of a massive wood-pulp project that would require converting 300,000 hectares of Yayasan Sabah’s natural forests to acacia plantations.

To some observers it was clear the Benta Wawasan project would never actually be completed. Instead the scheme prompted an orgy of destructive logging. Once the area was stripped of trees, the project collapsed, leaving behind what was mostly a deforested wasteland. Worse, the debacle spurred early re-logging of nearly 750,000 hectares of the concession, further degrading timber stocks and the ecological function of those forests.

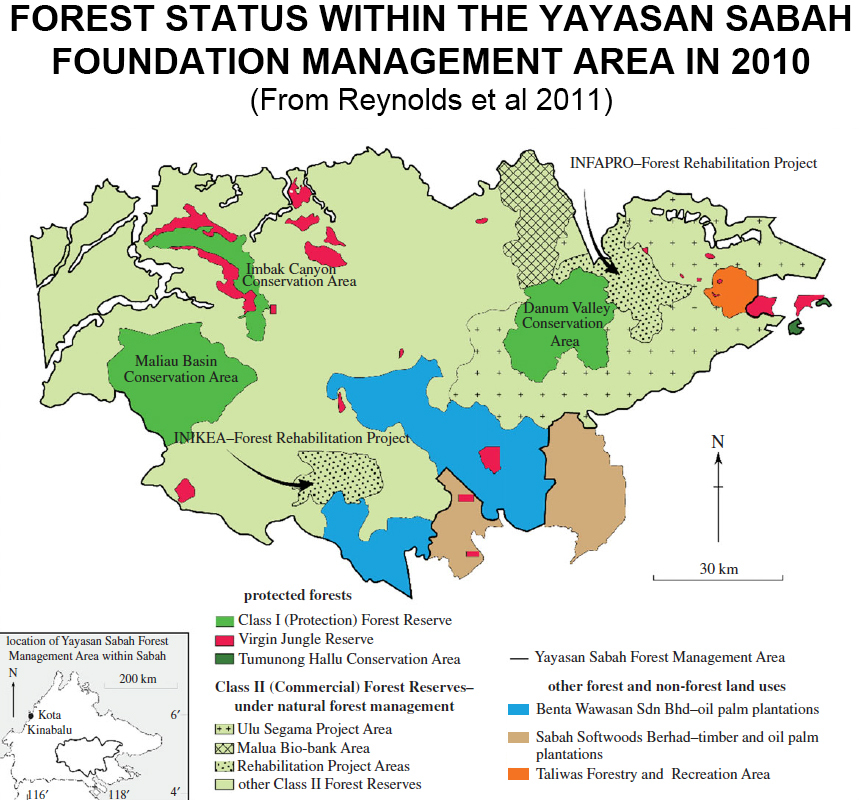

Map showing Yayasan Sabah Foundation Management Area in 2010. From a paper published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B by Reynolds el al (2011). Click image to enlarge.

But while logging depleted timber stocks, some of the remaining forests in the concession retained substantial ecological value, including large populations of endangered orangutans and Bornean elephants. Importantly, some of the area was still covered by lowland rainforest, the most endangered type of forest on the island of Borneo. The area also included islands of intact primary forest, which conservationists wanted to see connected by habitat corridors.

Outside Yayasan Sabah, vast areas of forests and agroforests in Sabah had given way to monoculture plantations, mostly oil palm plantations. Most of this expansion however had occurred in areas zoned by the government for agricultural activity outside reserves or alienated lands. Yayasan Sabah was zoned for forestry: timber harvesting. But that would be soon to change due to Yayasan Sabah’s dire financial outlook.

Sam Mannan, the director of the forestry department who had been relieved of his duties when he objected to the acacia scheme in 1999, was faced with a difficult situation. Yayasan Sabah was headed toward bankruptcy, which would likely result in the area being re-zoned for more profitable activities, namely palm oil production. At the same time, the concession served as critical habitats for endangered wildlife.

Rainforest in Imbak Canyon, Sabah, Malaysia. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

So Mannan made the controversial decision to establish oil palm plantations on 100,000 hectares of land cleared for the failed Benta Wawasan project. The idea being that oil palm would boost Yayasan Sabah’s fortunes, while yielding more money and political will for conservation. It was indeed a trade-off: today there are some 80,000 hectares of oil palm within the concession, yet there is also now more than 500,000 hectares of totally protected forests, not including the 203,000 added in Sabah last month. These new Class I Reserves play an important role in connecting the “crown jewels” of Borneo: mega-diverse pockets of rainforest in Yayasan Sabah’s Danum Valley, Maliau Basin and Imbak Canyon.

That decision has now put Mannan on the spot. Last week Jimmy Wong Sze Phin, a Kota Kinabalu Member of Parliament, criticized the forestry director and said the move violated the standards of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), an eco-certification platform for palm oil.

“How did they even approve the clearing of land and planting of oil palm by Yayasan Sabah in the middle of the forest?”, Wong was quoted as saying by The Rayak Post. “This is the first time oil palm has been planted in a forest reserve located in the heart of Borneo and not in a plantation.”

Oil palm plantation in Sabah, Malaysia. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

Paradoxically, Wong also spoke out against the Forestry Department’s efforts to stop encroachments by small palm oil companies into forest reserves. While Wong characterized those as local smallholders, Mannan countered that they were illegal encroachers with links to bigger companies, not poor farmers.

“We destroyed about 40,000 hectares of illegal oil palm in forest reserves over the past ten years,” said Mannan. “[Wong] is trying to is trying to portray the encroachers as down-trodden peasants. They in fact included ex-government servants who used to earn five-figure incomes.”

Mannan added that his goal is to protect 30 percent of Sabah by 2030, under TPAs (Totally Protected Areas) including as much “good forest” as possible. In secondary forests, he’s pushing for better forest management practices, like reduced impact logging with independent third party auditing. But he acknowledged that reaching that objective will require compromises.

“Compromises have to be made so conservation wins handsomely in the end,” he said. “Pragmatism is a word many people hate, but the reality is if we want all, we will end up losing all.”

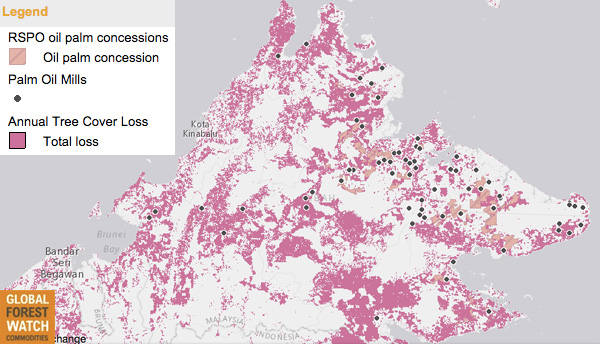

According to data from Global Forest Watch, Sabah experienced substantial change in tree cover between 2001 and 2012, losing nearly 900,000 hectares but gaining back just over 600,000 ha. Those numbers reflect active logging and turnover of oil palm plantations, which are typically replanted on a 20-30 year cycle. Other research, which separated out logging concessions and intact forest, found that Sabah’s intact forest cover declined from 58,000 square kilometers in 1973 to 14,000 in 2010.

Map of logging roads in Sabah

Map of forest clearance in Sabah

Map of logging in Sabah. All maps from DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101654

]

Related articles