Bulldozer at a conventional logging site in Borneo

Eighty percent of the rainforests in Malaysian Borneo have been heavily impacted by logging, finds a comprehensive study that offers the first assessment of the spread of industrial logging and logging roads across areas that were considered some of Earth’s wildest lands less than 30 years ago.

The research, conducted by a team of scientists from the University of Tasmania, University of Papua New Guinea, and the Carnegie Institution for Science, is based on analysis of satellite data using Carnegie Landsat Analysis System-lite (CLASlite), a freely available platform for measuring deforestation and forest degradation. It estimated the state of the region’s forests as of 2009.

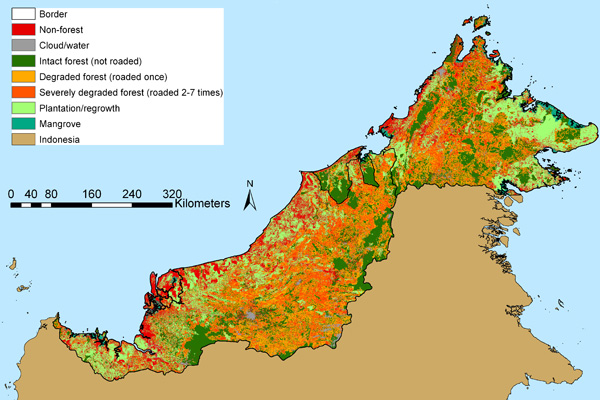

The study uncovered some 226,000 miles (364,000 km) of roads across Sabah and Sarawak, and found that roughly 80 percent of the two states have been impacted by logging or clearing. At best, only 45,400 square kilometers of forest ecosystems in the region remain intact.

“The extent of logging in Sabah and Sarawak documented in our work is breathtaking,” said study co-author Phil Shearman of the University of Papua New Guinea. “The logging industry has penetrated right into the heart of Borneo and very little rainforest remains untouched by logging or clearfell in Malaysian Borneo.”

“There is a crisis in tropical forest ecosystems worldwide, and our work documents the extent of the crisis on Malaysian Borneo,” added lead author Jane Bryan of the University of Tasmania. “Only small areas of intact forest remain in Malaysian Borneo, because so much has been heavily logged or cleared for timber or oil palm production.

“Rainforests that previously contained lots of big old trees, which store carbon and support a diverse ecosystem, are being replaced with oil palm or timber plantations, or hollowed out by logging.”

The state of forests in Malaysian Borneo (Sabah and Sarawak) in 2009. Note that the authors call their estimates of degraded forest “conservative”. While the study didn’t assess forest cover in Indonesian Borneo, the authors indicate the situation is similar.

Malaysian Borneo’s rainforests are home to a number of charismatic species, including Bornean orangutans, pygmy elephants, clouded leopards, proboscis monkeys, and Sumatran rhinos, which are on the edge of extinction. Its ecosystems also store vast amounts of carbon, which is released through forest degradation and clearance, land-clearing fires, and peatlands drainage and conversion to plantations.

The new analysis shows that logging and conversion have taken a heavy toll in the two states. One reason the impact of logging has been greater in Borneo than regions like Latin America and Central Africa is the nature of the island’s forests, which have a high density of commercially exploitable dipterocarp trees. Therefore loggers in Malaysian Borneo extract a much higher volume of trees per hectare, causing considerable damage and requiring longer harvest cycles. Low returns between harvests increase pressure to convert logged-over forests for timber and oil palm plantations.

Logging road in Malaysian Borneo in 2012. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

“Under this logging regime, the majority of commercial Dipterocarps (> 60 cm diameter at breast height) are felled and harvested in the first cycle (> 45 cm in Sarawak for non-Dipterocarp species), generally yielding 50-150 m3ha-1 of timber in the first harvest, with the aim of securing sufficient regeneration of commercial trees to allow a second harvest 25-30 years later,” the authors write. “Substantial damage to soil, waterways and forest structure and residual trees is caused by this form of logging, with progressive degradation of biomass over repeated harvest cycles. Bulldozers impact approximately 30-40% of the logged area and damage is caused to 40-70% of residual trees. For these reasons initial timber yields cannot be maintained over multiple harvest cycles, with 25-30 years between harvests too short a period to allow regeneration of timber stocks.”

The result is severe damage to forests: 44 percent of the region’s forests were classified as “degraded” or “severely degraded,” while another 28 percent had been converted to plantations or was in the process of recovering from logging.

“There are very few areas of rainforest in the Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak that haven’t already been logged or cleared – and a lot of this has happened since 1990,” Bryan told mongabay.com.

Time series showing roads and degraded forest metastasizing across an area in Sarawak.

The study also assessed forest cover in protected areas. It found that in 2009 only 8 percent of Sabah was covered by intact forest under designated protected areas. That represented 31 percent of Sabah’s remaining intact forest cover. In Sarawak, the situation in 2009 was even bleaker: only 3 percent of land cover consisted of legally protected intact forest. The results indicate that 85 percent of Sarawak’s intact forest cover is unprotected.

|

But the situation in Sabah is changing. Since 2009, the Forestry Department has moved to set aside several blocks of high conservation value within the Yayasan Sabah concession, an area of roughly a million hectares. These forests have been re-zoned as “Class I” forest reserves, making them off-limits to logging or conversion. In other areas, the Sabah Forestry Department is mandating certification when concessions in logged-over forests come up for renewal. The idea is to boost long-term productivity by making selective logging in secondary forests more sustainable, according to the agency’s director, Sam Mannan.

“There is very little primary forests left in Sabah, but where they exist, we are working to ensure they are protected,” Mannan told mongabay.com. “Recently added Class I areas consist of logged-over forests. The future of rainforests in Sabah lies with the logged over forests.”

“All long term licensees, meaning 99 percent of Sabah, will need to be certified under any internationally recognized forest certification scheme, including the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), by 2014.”

Mannan added that more up-to-date satellite imagery would help countries like Malaysia better manage forest resources, including identifying areas that should be set aside for protection.

“Satellite companies should give rainforest nations images for free and in real time,” he said.

Conventional logging operation in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo

The study is based on freely-available satellite imagery from NASA’s Landsat, which captures images of every point on the planet every 16 days. The satellite data was analyzed using CLASlite, software that was developed by a team led by Greg Asner at the Carnegie Institution for Science.

Other researchers have mapped Malaysian Borneo’s forest cover before, but the new study marks the first time that degradation and logging roads have been comprehensively documented across the region, according to the authors.

“The sheer extent of logging, that logging roads penetrate almost the entire area of remaining forests in Sabah and Sarawak may be a surprise to many – that’s because most previous studies have used low resolution imagery to map forests, and you simply can’t ‘see’ logging unless you use high resolution imagery like we did,” the authors told mongabay.com via email, adding that separating logged and unlogged forests was a “major challenge.”

| RESPONSES: AUTHORS BRYAN & SHEARMAN

What are the most important findings? There were two important findings. The first is that there are very few areas of rainforest in the Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak that haven’t already been logged or cleared – and a lot of this has happened since 1990. We estimate that only about 22% of the land area of Malaysian Borneo is still covered by forests that have not been logged, and that’s being conservative. The sheer extent of logging, that logging roads penetrate almost the entire area of remaining forests in Sabah and Sarawak may be a surprise to many – that’s because most previous studies have used low resolution imagery to map forests, and you simply can’t ‘see’ logging unless you use high resolution imagery like we did. The second finding was that in contrast to Malaysian Borneo, the nation of Brunei which shares a border with Malaysian Borneo, has managed to keep the majority of its forests unlogged. The difference between the two countries is quite startling. On the Malaysian side of the border, we found that there was a really dense pattern of logging roads and logging skid trails built through the forest, which stops right at the border. On the other side in Brunei, the forests were largely unbroken by any roads or skid trails. On one side of the border, there was heavy logging since 1990, and on the other side virtually none. It’s quite a contrast. Over the past decades, Brunei built its wealth on oil and gas extraction and excluded logging, which has been vastly more successful in forest protection. It has meant that today Brunei still has more than half of its land area covered by intact forest ecosystems, while Malaysian Borneo has at most 22%. But that said, Brunei is much smaller – only about 3% of the area of Malaysian Borneo. Do you have any conservation policy recommendations? Comparing what has happened in Brunei where more than half of the land area is still covered by unlogged forests, with Sabah and Sarawak, where at most 22% remains is instructive. We think Brunei shows that excluding logging entirely is an effective way to protect forests in the long term, but it does mean that a nation would need an alternative income stream. For Brunei, that came from oil and gas. If you look at the United Nations Human Development Index, which includes life expectancy, education and national income, Brunei is ahead of Malaysia. This is good news for other mineral rich tropical nations with large areas of unlogged forests remaining – it shows that there is no need to rely on industrial scale, widespread logging to build national wealth and well being. Excluding the logging industry entirely to protect forests is a feasible option without necessarily harming national development and economic goals. The comparison of Brunei with Malaysian Borneo also shows that excluding logging entirely is likely to be much more successful at forest protection in the long term than relying on a small network of protected areas. For Sabah and Sabah and Sarawak, where almost all forests have already been heavily logged, something different is needed. On the one hand, because there are so few unlogged forests remaining, strengthening protection of these areas in protected areas makes sense. But because so few forests remain unlogged in Sabah and Sarawak, the lion’s share of forest protection efforts need to focus on already logged forests. Logged forests in the tropics tend to be forests in transition. Logged forests are far more likely to be cleared than unlogged forests, with roads opening up the place to serial logging events. In Sabah and Sarawak in many places we found multiple roads being built through the same forests over a period of 20 years. Repeated logging within a short period of time means that forests are getting progressively hollowed out, with the end point being their conversion – either deliberately for oil palm, or ‘accidentally’ via fire. This is where the extensively logged forests we documented in Sabah and Sarawak are likely to go unless their regeneration is ensured by protection efforts. This is where we think the REDD program could still have an important role to play. The original intent of REDD was to provide tropical forested nations with an alternative source of income to industrial logging or agriculture of the kind that involves deforestation. The Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak have a huge opportunity to wind back the logging industry, prevent further logging of large areas of already logged forest, allow their full regeneration, and replace the income with carbon payments. At the moment the alternative scenario is to pin forest conservation hopes solely on the protected area network, in which case we can expect about 8% of Sabah’s and 3% of Sarawak’s formerly vast forest ecosystems to remain undamaged in the future. |

“You can only really tell remotely whether tropical rainforest has been logged or not using high resolution imagery (imagery with a pixel size of 30 meters or less), and the higher the resolution of the imagery, the more time and computer processing power is required. Luckily Greg Asner’s lab at the Carnegie Institution for Science has spent the past decade working on that problem. Their CLASlite program is excellent at resolving this issue. When you combine the output of CLASlite with a map of logging roads which we digitized as part of our study, we were able to construct a very detailed map of forest cover and the extent of logging activities.”

Asner called the results of the study “sobering.”

“The problem with previous monitoring reports is that they have been based on satellite mapping methods that have missed most of the forest degradation in Malaysian Borneo, and elsewhere throughout the tropics,” he said in a press release. “I’m talking about heavy logging that leaves a wake of forest degradation, even though the area may still look like forest in conventional satellite imagery. With the CLASlite system, we can see the effects of logging on the inner canopy of the forest. The system revealed extremely widespread degradation in this case.”

As a point of comparison, the researchers used Brunei, the tiny oil-rich sultanate that separates Sabah and Sarawak. Brunei relies on offshore oil and gas — and associated services — to fuel its economy. Unlike Sabah and Sarawak, it has largely left its forests for the birds. The difference in policy offers a stark contrast when it comes to forest cover: nearly two-thirds of its forest cover is “intact” and only 15 percent is classified as “degraded” or “severely degraded.”

“The difference between the two countries is quite startling,” the authors said. “On the Malaysian side of the border, we found that there was a really dense pattern of logging roads and logging skid trails built through the forest, which stops right at the border. On the other side in Brunei, the forests were largely unbroken by any roads or skid trails.”

The authors argue that Brunei’s example shows that excluding logging from primary forests is a far more effective conservation strategy than trying to manage old-growth forests through reduced-impact logging.

“The history of forestry in Sarawak and Sabah indicates that attempting to reform the logging industry does not result in meaningful forest conservation,” they write. “A far better approach, as shown in Brunei, is to prevent logging of natural forests in the first instance, or in places where logging has occurred, to exclude further logging from what remains.”

“In Sarawak and Sabah in particular, and globally across the tropics, the crisis in tropical forests is now so severe that any further sacrifice of primary ecosystems to the industrial logging industry ought to be out of the question for all who seriously seek to maintain biodiversity and forest ecosystems.”

The challenge for Sabah and Sarawak however will be making the transition away from forestry and plantation agriculture. At present there is intense political pressure to turn over non-productive logged-over forests for conversion to plantations rather than wait for them to recover or turn them over for protected areas. While both states have considerable offshore energy reserves, revenue flows from those resources accrue to the central government. So neither Sabah nor Sarawak can currently rely on Brunei’s economic model.

Some, including the authors, have suggested that the Reducing Emissions from Degradation and Deforestation (REDD+) program could provide sufficient economic incentive for keeping forests standing in Malaysian Borneo. But as currently designed, only limited areas of the region’s forests would quality for carbon payments. Furthermore, the current state of the carbon market means those carbon payments are unlikely to be competitive with the alternative: clearing forests for timber and palm oil. So in the near term, the fate of unlogged forests in Malaysian Borneo will likely be determined by the will of Malaysians to keep them standing.

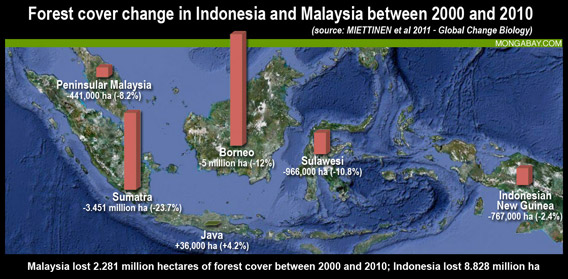

Deforestation in Indonesia and Malaysia between 2000 and 2010. Note that Borneo as a whole lost 12 percent of its forest cover (and 25 percent of its peatlands) during that time period, according to a paper published by Jukka Miettinen and colleagues in Global Change Biology in 2011.

CITATION: Jane E. Bryan, Philip L. Shearman, Gregory P. Asner, David E. Knapp, Geraldine Aoro, Barbara Lokes (2013). Extreme Differences in Forest Degradation in Borneo: Comparing Practices in Sarawak, Sabah, and Brunei. PLoS ONE 8(7): e69679. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069679

Related articles

NGO: Malaysian leader worth $15 billion despite civil-servant salary; timber corruption suspected

(09/19/2012) Abdul Taib Mahmud, who has headed the Malaysian state of Sarawak for over 30 years, is worth $15 billion according to a new report by the Bruno Manser Fund. The report, The Taib Timber Mafia, alleges that Taib has used his position as head-of-state to build up incredible amounts of wealth by employing his family or political nominees to run the state’s logging, agriculture, and construction businesses. Some environmental groups claim that Sarawak has lost 90 percent of its primary forests to logging, while indigenous tribes in the state have faced the destruction of their forests, harassment, and eviction.

Sabah protects 700 sq mi of rainforest in Borneo

(08/30/2012) Sabah, a state in Malaysian Borneo, has reclassified 183,000 hectares (700 sq km) of forest zoned for logging concessions as protected areas.

Industrial logging leaves a poor legacy in Borneo’s rainforests

(07/17/2012) For most people “Borneo” conjures up an image of a wild and distant land of rainforests, exotic beasts, and nomadic tribes. But that place increasingly exists only in one’s imagination, for the forests of world’s third largest island have been rapidly and relentlessly logged, burned, and bulldozed in recent decades, leaving only a sliver of its once magnificent forests intact. Flying over Sabah, a Malaysian state that covers about 10 percent of Borneo, the damage is clear. Oil palm plantations have metastasized across the landscape. Where forest remains, it is usually degraded. Rivers flow brown with mud.

Charts: deforestation in Indonesia and Malaysia, 2000-2010

(07/15/2012) Indonesia and Malaysia lost more than 11 million hectares (42,470 square miles) of forest between 2000 and 2010, according to a study published last year in the journal Global Change Biology. The area is roughly the size of Denmark or the state of Virginia. The bulk of forest loss occurred in lowland forests, which declined by 7.8 million hectares or 11 percent on 2000 cover. Peat swamp forests lost the highest percentage of cover, declining 19.7 percent. Lowland forests have historically been first targeted by loggers before being converted for agriculture. Peatlands are increasingly converted for industrial oil palm estates and pulp and paper plantations.

In pictures: Rainforests to palm oil

(07/02/2012) In late May I had the opportunity to fly from Kota Kinabalu in Malaysian Borneo to Imbak Canyon and back. These are some of my photos. Historically Borneo was covered by a range of habitats, including dense tropical rainforests, swampy peatlands, and natural grasslands. But its lowland forests have been aggressively logged for timber and then converted for oil palm plantations.

(03/28/2011) Images from Google Earth show a sharp contract between forest cover in Sarawak, a state in Malaysian Borneo, and the neighboring countries of Brunei and Indonesia at a time when Sarawak’s Chief Minister Pehin Sri Abdul Taib Mahmud is claiming that 70 percent of Sarawak’s forest cover is intact.