Philip M. Fearnside is a Research Professor at the National Institute for Research in the Amazon (INPA) in Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil since 1978. Author of over 450 publications, his honors include Brazil’s National Ecology Prize, the UN Global 500 award, the Conrad Wessel, Chico Mendes and Benchimol prizes, the Scopus prize and membership in the Brazilian Academy of Sciences. In 2006 he was identified by Thompson-ISI as the world’s second most-cited scientist on the subject of global warming.

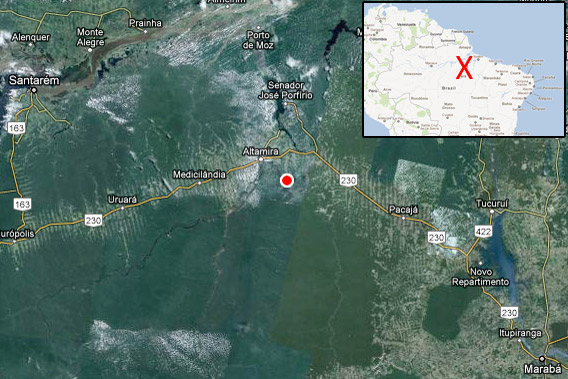

Belo Monte location. Courtesy of Google Earth.

Brazil’s Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu River is now under construction despite its many controversies. The Brazilian government has launched an unprecedented drive to dam the Amazon’s tributaries, and Belo Monte is the spearhead for its efforts. Brazil’s 2011-2020 energy-expansion plan calls for building 48 additional large dams, of which 30 would be in the country’s Legal Amazon region1. Building 30 dams in 10 years means an average rate of one dam every four months in Brazilian Amazonia through 2020. Of course, the clock doesn’t stop in 2020, and the total number of planned dams in Brazilian Amazonia exceeds 60 [2,3].

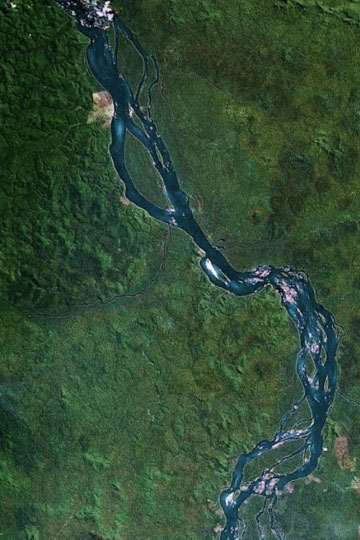

The Belo Monte Dam itself has substantial impacts. It is unusual in not having its main powerhouse located at the foot of the dam, where it would allow the water emerging from the turbines to continue flowing in the river below the dam. Instead, most of the river’s flow will be detoured from the main reservoir through a series of canals interlinking five dammed tributary streams, leaving the “Big Bend” of the Xingu River below the dam with only a tiny fraction of its normal annual flow.

A section of the Xingu River as viewed by Google Earth. |

What is known as the “dry stretch” of 100 km between the dam and the main powerhouse includes two indigenous reserves, plus a population of traditional Amazonian riverside dwellers. Since the impact on these people is not the normal one of being flooded by a reservoir, they were not classified as “directly impacted” in the environmental study and have not had the consultations and compensations to which directly impacted people are entitled. The human rights commission of the Organization of American States (OAS) considered the lack of consultation with the indigenous people a violation of the international accords to which Brazil is a signatory, and Brazil retaliated by cutting off its dues payments to the OAS. The dam will also have more familiar impacts by flooding about one fourth of the city of Altamira, as well as the populated rural areas that will be flooded by the reservoir.

What is most extraordinary is the project’s potential impact on vast areas of indigenous land and tropical rainforest upstream of the reservoir, but the environmental impact studies and licensing have been conducted in such a way as to avoid any consideration of these impacts. The original plan for the Xingu River called for five additional dams upstream of Belo Monte [4,5,6]. These dams, especially the 6,140 square kilometer Babaquara Dam (now renamed the “Altamira” Dam), would store water that could be released during the Xingu River’s low-flow period to keep the turbines at Belo Monte running.

The Xingu has a large annual oscillation in water flow, with as much as 60 times more water in the high-flow as compared to the low-flow period. During the low-flow period the unregulated flow of the river is insufficient to turn even one of the turbines in Belo Monte’s 11,000 MW main powerhouse [7]. Since the Belo Monte Dam itself will be essentially ‘run-of-the-river’, without storing water in its relatively small reservoir, economic analysis suggests that the dam by itself won’t be economically viable [8,9].

The official scenario for the Xingu River changed in July 2008 when Brazil’s National Council for Energy Policy (CNPE) declared that Belo Monte would be the only dam on the Xingu River. However, the council is free to reverse this decision at any time. Top electrical officials considered the CNPE decision a political move that is technically irrational [10]. Brazil’s current president blocked creation of an extractive reserve upstream of Belo Monte on the grounds that it would hamper building “dams in addition to Belo Monte” [11]. The fact that the Brazilian government and various companies are willing to invest large sums in Belo Monte may be an indication that they do not expect history to follow the official scenario of only one dam [12].

In addition to their impacts on tropical forests and indigenous peoples, these dams would make the Xingu a source of greenhouse-gas emissions, especially methane (CH4) which forms when dead plants decay on the bottom of a reservoir where the water contains no oxygen [13,14]. The Babaquara Dam’s 23m vertical variation in water level, annually exposing and flooding a 3,580 square kilometer drawdown zone would make the complex a virtual ‘methane factory’. The reservoir’s flooding of soft vegetation growing in the drawdown zone converts carbon from CO2 removed from the atmosphere by photosynthesis into CH4, with a much higher impact on global warming [15,16,17].

Dams in the Amazon. Courtesy of International Rivers. Click image for expandable map. |

It is Belo Monte’s role in the decision-making and licensing process that has the farthest-reaching consequences for Amazonia. Brazil’s 1988 constitution, enacted when plans for Belo Monte and the other Xingu dams were in full swing, increased the protection for indigenous peoples by requiring approval by the national congress for dams affecting indigenous land. This led to redesign of Belo Monte itself to avoid directly flooding indigenous land, and to a de facto policy of not mentioning the upstream dams. Then, in 2005, Belo Monte was suddenly approved by the senate in 48 hours under a ‘urgent, super-urgent’ regime with no debate and without the constitutionally required consultations with the tribes. This opened the way for consideration of multiple dams affecting indigenous peoples, including the upstream dams on the Xingu.

In February 2010, Belo Monte was granted a ‘partial’ license to allow installation of the construction site without completing the environmental approval of the project as a whole. Partial licenses do not exist in Brazil’s legislation, and this device represents a step in allowing dam projects to make themselves into faits accomplis irrespective of their impacts. In January 2011 a preliminary license was granted, with 40 ‘conditionalities’ that would have to be met before an installation license would be granted to build the dam.

Very little was done in the succeeding months to meet the requirements, and only five of the 40 had been met in June 2011 when an installation license was suddenly granted. The approval came after the head of the environmental agency had been forced to resign: he had supported his technical staff, who were opposed to approving the license without meeting the requirements. A new head of the agency was appointed who approved the license without fulfilling the conditionalities, opening the way for approving projects for dams, highways and other infrastructure that await fulfillment of similar requirements. The approval by replacement of the key official also opens a precedent that can allow projects to move forward no matter what their impacts (see the new agency head’s very revealing interview on Australian television here).

At the time Belo Monte’s installation license was approved 12 court cases were pending decisions regarding irregularities in the licensing process. What will happen if any of these cases is decided against Belo Monte after vast sums have been spent in building the dam? Would the government simply back down and walk away? The stage appears set for breaking down Brazil’s environmental licensing system even further, opening the way for the many other controversial dams planned in the Amazon.

References:

- Brazil, MME (Ministério de Minas e Energia). 2011. Plano Decenal de Expansão de Energia 2020. MME, Empresa de Pesquisa Energética (EPE). Brasília, DF, Brazil. 2 vols.

- Brazil, ELETROBRÁS. 1987. Plano 2010: Relatório Geral. Plano Nacional de Energia Elétrica 1987/2010 (Dezembro de 1987). Centrais Elétricas do Brasil (ELETROBRÁS), Brasília, DF, Brazil. 269 pp.

- Fearnside, P.M. 1995. Hydroelectric dams in the Brazilian Amazon as sources of ‘greenhouse’ gases. Environmental Conservation 22(1): 7-19. Doi: 10.1017/S0376892900034020

- Santos, L.A.O. & L.M.M. de Andrade (eds.) 1990. Hydroelectric Dams on Brazil’s Xingu River and Indigenous Peoples. Cultural Survival Report 30. Cultural Survival, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A. 192 pp.

- Sevá Filho, A.O. (ed.) 2005. Tenotã-mõ: Alertas sobre as conseqüências dos projetos hidrelétricos no rio Xingu, Pará, Brasil,” International Rivers Network, São Paulo, Brazil. 344 pp.

- Fearnside, P.M. 2006. Dams in the Amazon: Belo Monte and Brazil’s hydroelectric development of the Xingu River Basin. Environmental Management 38(1): 16-27. Doi: 10.1007/s00267-005-00113-6

- Molina Carpio, J. 2009. Questões hidrológicas no EIA Belo Monte. pp. 95-106 In: S.M.S.B.M. Santos & F.M. Hernandez (eds.). Painel de Especialistas: Análise Crítica do Estudo de Impacto Ambiental do Aproveitamento Hidrelétrico de Belo Monte. Painel de Especialistas sobre a Hidrelétrica de Belo Monte, Belém, Pará, Brazil. 230 pp.

- Sousa Júnior, W.C. & J. Reid, 2010. Uncertainties in Amazon hydropower development: Risk scenarios and environmental issues around the Belo Monte dam. Water Alternatives 3(2): 249-268.

- Sousa Júnior, W.C. de, J. Reid & N.C.S. Leitão. 2006. Custos e Benefícios do Complexo Hidrelétrico Belo Monte: Uma Abordagem Econômico-Ambiental. Conservation Strategy Fund (CSF), Lagoa Santa, Minas Gerais, Brazil. 90 pp.

- OESP. 2008. Governo desiste de mais hidrelétricas no Xingu. O Estado de São Paulo (OESP), 17 de julho de 2008, p. B-8.

- Angelo, C. 2010. “PT tenta apagar fama ‘antiverde’ de Dilma.” Folha de São Paulo, 10 October 2010, p. A-15.

- Fearnside, P.M. 2011a. Will the Belo Monte Dam’s benefits outweigh the costs? Latin America Energy Advisor, 21-25 Feb. 2011, p. 6. [http://www.thedialogue.org]

- Fearnside, P.M. 2002. Greenhouse gas emissions from a hydroelectric reservoir (Brazil’s Tucuruí Dam) and the energy policy implications. Water, Air and Soil Pollution 133(1-4): 69-96. Doi: 10.1023/A:1012971715668

- Fearnside, P.M. 2004. Greenhouse gas emissions from hydroelectric dams: controversies provide a springboard for rethinking a supposedly “clean” energy source. Climatic Change 66(2-1): 1-8. Doi: 10.1023/B:CLIM.0000043174.02841.23

- Fearnside, P.M. 2008. Hidrelétricas como “fábricas de metano”: O papel dos reservatórios em áreas de floresta tropical na emissão de gases de efeito estufa. Oecologia Brasiliensis 12(1): 100-115. Doi: 10.4257/oeco.2008.1201.11

- Fearnside, P.M. 2009. As hidrelétricas de Belo Monte e Altamira (Babaquara) como fontes de gases de efeito estufa. Novos Cadernos NAEA 12(2): 5-56.

- Fearnside, P.M. 2011b. Gases de efeito estufa no EIA-RIMA da Hidrelétrica de Belo Monte. Novos Cadernos NAEA 14(1): 5-19.

Related articles

International Labor Organization raps Brazil over monster dam

(03/07/2012) The UN’s International Labor Organization (ILO) has released a report stating that the Brazilian government violated the rights of indigenous people by moving forward on the massive Belo Monte dam without consulting indigenous communities. The report follows a request last year by the The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights for the Brazilian government to suspend the dam, which is currently being constructed on the Xingu River in the Amazon.

Brazil begins preliminary damming of Xingu River as protests continue

(01/19/2012) Damming of the Xingu River has begun in Brazil to make way for the eventual construction of the hugely controversial, Belo Monte dam. The Norte Energia (NESA) consortium has begun building coffer dams across the Xingu, which will dry out parts of the river before permanent damming, reports the NGO International Rivers. Indigenous tribes, who have long opposed the dam plans on their ancestral river, conducted a peaceful protest that interrupted construction for a couple hours.

(11/09/2011) Indigenous communities do not have the right to free, prior and informed consultation on the Belo Monte dam because its infrastructure and reservoirs would not be physically located on tribal lands, ruled a Brazilian court.

Occupy Belo Monte: indigenous stage “permanent” protest against Amazon dam in Brazil

(10/27/2011) Hundreds of people are participating in a protest against the controversial Belo Monte dam in Altamira, Brazil, reports Amazon Watch.

Brazil boycotts OAS meeting after sharp human rights rebuke over giant Amazon dam

(10/27/2011) Brazil refused to attend a hearing convened by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) of the Organization of American States (OAS) over the the controversial Belo Monte dam, reports Amazon Watch, a group campaigning against the hydroelectric project.

Brazil plans $120 billion in infrastructure investments in the Amazon by 2020

(10/19/2011) Brazil’s push to expand infrastructure in the Amazon region will require at least 212 Brazilian reals ($120 billion) in public and private sector investment by 2020, reports Folha de Sao Paulo.

Protesters demand end to controversial Amazon dam

(08/23/2011) Protesters in dozens of cities demanded Brazil abandon a plan to build a dam on one of the Amazon’s largest tributaries, reports Amazon Watch, an NGO that helped organize the events.

(07/17/2011) Curt Trennepohl, president of Brazil’s environmental protection agency (IBAMA), caused an uproar last week when he told an Australian TV crew that his agency’s role “is not caring for the environment, but to minimize the impact”. Later when Trennepohl believed the cameras were off he went on to say Brazilian indigenous tribes would suffer the same fate as Australia’s Aborigines, reports Folha de S.Paulo.

Picture of the day: waterfall on the endangered Xingu river

(07/11/2011) Characterized by crystal-clear waters and surrounding by tropical rainforest, the Xingu is considered one of the most beautiful rivers in the Amazon basin. Yet the Xingu is on the brink of destruction due Belo Monte, an $18.5 billion hydroelectric project backed by Brazilian government energy companies; Vale, mining giant; Bertin, one of the largest meat processing firms; and nearly a dozen other companies. The vast majority of Belo Monte’s funding comes from the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES).

Last chance to see: the Amazon’s Xingu River

(06/15/2011) Not far from where the great Amazon River drains into the Atlantic, it splits off into a wide tributary, at first a fat vertical lake that, when viewed from satellite, eventually slims down to a wild scrawl through the dark green of the Amazon. In all, this tributary races almost completely southward through the Brazilian Amazon for 1,230 miles (1,979 kilometers)—nearly as long as the Colorado River—until it peters out in the savannah of Mato Grosso. Called home by diverse indigenous tribes and unique species, this is the Xingu River.

(06/03/2011) As an American I know a lot about shame — the U.S. government and American companies have wrought appalling amounts of damage the world over. But as an admirer of Brazil’s recent progress toward an economy that recognizes the contributions of culture and the environment, this week’s decision to move forward on the Belo Monte dam came as a shock. Belo Monte undermines Brazil’s standing as a global leader on the environment. Recent gains in demarcating indigenous lands, reducing deforestation, developing Earth monitoring technologies, and enforcing environmental laws look more tenuous with a project that runs over indigenous rights and the environment.

Amazon mega-dam gets final approval

(06/01/2011) Brazilian authorities gave final approval to the controversial Belo Monte dam, reports AFP.

Violent protests follow approval of massive dam project in Patagonia

(05/16/2011) The wild rivers of Patagonia may soon never be the same. Last week, Chile’s Aysén Environmental Review Commission approved the environmental assessment of a five dam proposal on two rivers. The approval, however, is marred in controversy and has set off protests in many cities, including Santiago. Critics say the series of dams will destroy a largely untouched region of Patagonia.

Controversial Brazilian mega-dam receives investment of $1.4 billion

(05/02/2011) Brazil’s most controversial mega-dam, Belo Monte, which is moving full steam ahead against massive opposition, has received an extra infusion of cash from Vale, a Brazilian-run mining company.

Google Earth animation shows Brazilian plans to turn Amazon into ‘series of stagnant reservoirs’

(08/30/2010) The decision last week by the Brazilian government to move forward on the $17 billion Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu river will set in motion a plan to build more than 100 dams across the Amazon basin, potentially turning tributaries of the world’s largest river into ‘an endless series of stagnant reservoirs’, says a new short film released by Amazon Watch and International Rivers.

146 dams threaten Amazon basin

(08/19/2010) Although developers and government often tout dams as environmentally-friendly energy sources, this is not always the case. Dams impact river flows, changing ecosystems indefinitely; they may flood large areas forcing people and wildlife to move; and in the tropics they can also become massive source of greenhouse gases due to emissions of methane. Despite these concerns, the Amazon basin—the world’s largest tropical rainforest—is being seen as prime development for hydropower projects. Currently five nations—Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru—are planning over 146 big dams in the Amazon Basin. Some of these dams would flood pristine rainforests, others threaten indigenous people, and all would change the Amazonian ecosystem. Now a new website, Dams in Amazonia, outlines the sites and impacts of these dams with an interactive map.