- A new study finds orangutans in Indonesian Borneo in unprotected areas are being killed at a rate faster than what population viability analysis considers sustainable.

- Conflict between orangutans and humans is worst in areas that have been fragmented and converted for timber, wood-pulp, and palm oil production, but hunting is occurring in relatively intact forest zones away from industrial development

Bornean orangutan in Central Kalimantan. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

A comprehensive new study finds that orangutan populations in Indonesian Borneo are being diminished at unsustainable rates due to conflict with humans. The results suggest orangutans outside protected areas may be headed toward extinction.

The study, published Friday in PLoS One, is based on 18 months of interviews with nearly 7,000 people across 687 villages in areas where orangutans persist in East, Central, and West Kalimantan. The research involved 18 NGOs, including local and international organizations.

The study, which sought to address a dearth of quantitative data on human-orangutan conflict, asked villagers about their knowledge of wildlife laws and orangutan conflict and killing. The researchers tracked responses across age, ethnicity, religion, and livelihoods as well as geography and the villages’ proximity to industrial operations, including oil palm and pulp and paper plantations, mining areas, and logging concessions. Two-thirds of respondents were Dyaks, about a third were Malays and migrants, while less than one percent were punans, who until recently were nomadic forest people.

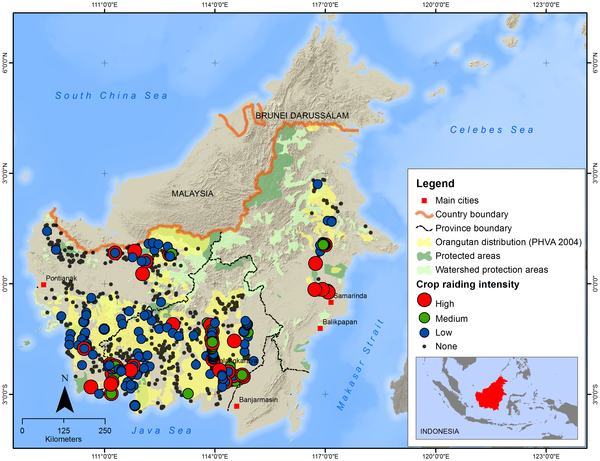

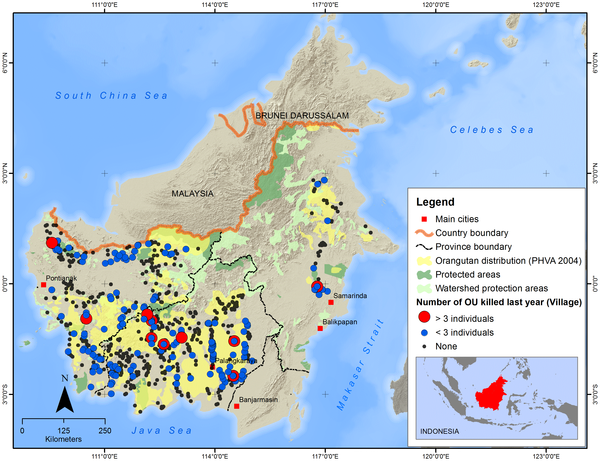

Crop raiding intensity in different villages across Kalimantan. High = reported conflict frequency every week; Medium = every month; Low = once a year or less frequently. Courtesy of PLoS One.

The assessment, which included responses only from people who were able to reliably differentiate orangutans from other primate species, found that only a small number of people have personally killed an orangutan, but that nearly a sixth of villages reported agricultural conflicts with orangutans and a quarter had killed at least one orangutan. At 18 percent, East Kalimantan had the highest rate of conflict, while West Kalimantan had the lowest at 12 percent.

Crop-raiding by orangutans was commonly cited as a reason for conflict in agricultural areas, while hunting for food was the prime motivation in relatively intact forest zones away from industrial development. Conflict and killing for crop-raiding was most frequent in village areas where palm oil, rice, and industrial pulp and paper was being produced. Those most likely to kill an orangutan were involved with logging, hunting or mining, rather than collection of non-wood forest products.

“Our data suggest that conversion of forests to other land uses can result in orangutans entering villagers’ gardens and raiding crops,” write the authors, led by Erik Meijaard, an ecologist formerly with The Nature Conservancy who now works for People and Nature Consulting International in Jakarta. “This form of direct conflict can result in killing.”

Crop raiding intensity in different villages across Kalimantan. High = reported conflict frequency every week; Medium = every month; Low = once a year or less frequently. Courtesy of PLoS One.

The study found marked differences in the level knowledge between different ethnic groups. 17 percent of respondents were unable to identify an orangutan, but that number was lower for traditional forest people: only 13 percent of Dyaks and less than 0.1 percent of Dyaks failed to distinguish orangutans from other primates. However migrants were considerably more likely than forest people to know that killing an orangutan was against the law. Overall 73 percent of villagers said they knew orangutan-killing was illegal under Indonesian law. 15 percent reported orangutans were protected under customary law known as adat.

The most troubling finding is the scale of orangutan killing, which the study estimated at 750-1790 in past year and 1970-3100 per year on average during respondents’ lifetimes — higher than previously thought.

“These killing rates… are high enough to pose a serious threat to the continued existence of orangutans in Kalimantan.”

Of particular concern is the implied impact of killing female orangutans, which have low reproductive rates due to the extended amount of time they spend rearing their young.

“Population viability studies of orangutans suggest that if annual mortality of females is higher than 1% then populations will go extinct,” write the authors, who go on to estimate the current kill rates of females at 0.9 percent and 3.6 percent, suggesting a dire future for orangutans in Indonesian Borneo.

Bornean orangutan with baby in Central Kalimantan. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

“These mortality rates caused by hunting alone are higher than the theoretical maximum mortality for population viability, suggesting that unless they can be reduced most Kalimantan populations will go extinct,” they write.

“The data suggest no orangutans outside Kalimantan’s protected areas are safe. They are either threatened by habitat degradation and deforestation, or they are threatened by ongoing hunting within their forest habitats.”

The authors conclude with a call to better target anti-killing measures to specific groups within Kalimantan. They note that because the vast majority of villagers don’t themselves kill orangutans there may be an opportunity to convince those who killing orangutans opportunistically that it is no longer socially acceptable to do so.

Orphaned orangutan in Central Kalimantan. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

CITATION: Meijaard E, Buchori D, Hadiprakarsa Y, Utami-Atmoko SS, Nurcahyo A, et al. (2011) Quantifying Killing of Orangutans and Human-Orangutan Conflict in Kalimantan, Indonesia. PLoS ONE 6(11): e27491. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027491

Related articles

Counting orangutans: the best way to survey the great apes

(03/28/2011) How do you count orangutans when they are difficult to spot in the wild given that they are shy, arboreal, and few and far between? To find a solution, biologists have turned to estimating orangutan populations by counting their nests, which the great apes make anew every night. In order to make the most accurate count possible, researchers have studied the different factors that could impact the success, or lack thereof, of nest-counters in mongabay.com’s open access journal Tropical Conservation Science.

Environmentalists must recognize ‘biases and delusions’ to succeed

(10/18/2010) As nations from around the world meet at the Convention on Biological Diversity in Nagoya, Japan to discuss ways to stem the loss of biodiversity worldwide, two prominent researchers argue that conservationists need to consider paradigm shifts if biodiversity is to be preserved, especially in developing countries. Writing in the journal Biotropica, Douglas Sheil and Erik Meijaard argue that some of conservationists’ most deeply held beliefs are actually hurting the cause.

Orangutan populations collapse in pristine forest areas

(08/12/2010) Orangutan encounter rates have fallen six-fold in Borneo over the past 150 years, report researchers writing in the journal PLoS One. Erik Meijaard, an ecologist with People and Nature Consulting International, and colleagues compared present-day encounter rates with collection rates from naturalists working in the mid-19th Century. They found orangutans are much rarer today even in pristine forest areas. The results suggest hunting is taking a toll on orangutan populations.

(07/29/2010) Many of the environmental issues facing Indonesia are embodied in the plight of the orangutan, the red ape that inhabits the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. Orangutan populations have plummeted over the past century, a result of hunting, habitat loss, the pet trade, and human-ape conflict. Accordingly, governments, charities, and concerned individuals have ploughed tens of millions of dollars into orangutan conservation, but have little to show in terms of slowing or reversing the decline. The same can be said about forest conservation in Indonesia: while massive amounts of money have been put toward protecting and sustainable using forests, the sum is dwarfed by the returns from converting forests into timber, rice, paper, and palm oil. So orangutans—and forests—continue to lose out to economic development, at least as conventionally pursued. Poor governance means that even when well-intentioned measures are in place, they are often undermined by corruption, apathy, or poorly-designed policies. So is there a future for Indonesia’s red apes and their forest home? Erik Meijaard, an ecologist who has worked in Indonesia since 1993 and is considered a world authority on orangutan populations, is cautiously optimistic, although he sees no ‘silver bullet’ solutions.

Palm oil both a leading threat to orangutans and a key source of jobs in Sumatra

(09/24/2009) Of the world’s two species of orangutan, a great ape that shares 96 percent of man’s genetic makeup, the Sumatran orangutan is considerably more endangered than its cousin in Borneo. Today there are believed to be fewer than 7,000 Sumatran orangutans in the wild, a consequence of the wildlife trade, hunting, and accelerating destruction of their native forest habitat by loggers, small-scale farmers, and agribusiness. Gunung Leuser National Park in North Sumatra is one of the last strongholds for the species, serving as a refuge among paper pulp concessions and rubber and oil palm plantations. While orangutans are relatively well protected in areas around tourist centers, they are affected by poorly regulated interactions with tourists, which have increased the risk of disease and resulted in high mortality rates among infants near tourist centers like Bukit Lawang. Further, orangutans that range outside the park or live in remote areas or on its margins face conflicts with developers, including loggers, who may or may not know about the existence of the park, and plantation workers, who may kill any orangutans they encounter in the fields. Working to improve the fate of orangutans that find their way into plantations and unprotected community areas is the Orangutan Information Center (OIC), a local NGO that collaborates with the Sumatran Orangutan Society (SOS).