Sprawl in the desert: urban sprawl spreading out from Las Vegas. A new study finds that to save life on Earth, society must confront human population and overconsumption of resources. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

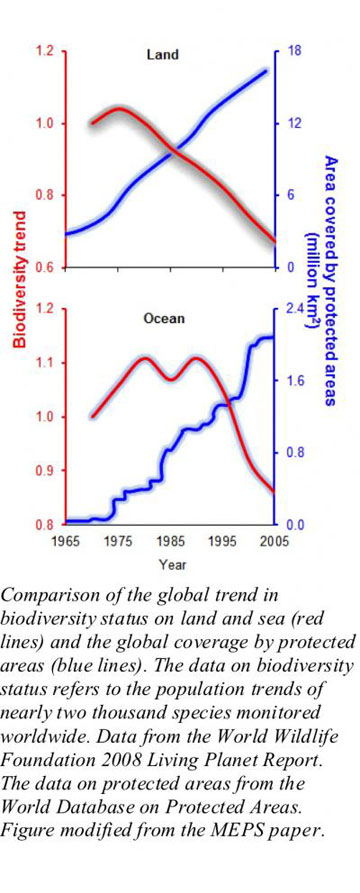

Since the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 protected areas have spread across the world. Today, over 100,000 protected areas—national parks, wildlife refuges, game reserves, marine protected areas (MPAs), wildlife sanctuaries, etc.—cover some 7.3 million square miles (19 million kilometers), mostly on land, though conservation areas in the oceans are spreading. While there are a number of reasons behind the establishment of protected areas, one of the most important is the conservation of wildlife for future generations. But now a new open access study in Marine Ecology Progress Series has found that protected areas are not enough to stem the loss of global biodiversity. Even with the volume of protected areas, many scientists say we are in the midst of a mass extinction with extinction levels jumping to 100 to 10,000 times the average rate over the past 500 million years. While protected areas are important, the study argues that society must deal with the underlying problems of human population and overconsumption if we are to have any chance of preserving life on Earth—and leaving a recognizable planet for our children.

“The global network of protected areas is a major achievement, and the pace at which it has been achieved is impressive,” says co-author Dr. Peter F. Sale, Assistant Director of the United Nations University’s Canadian-based Institute for Water, Environment and Health, in a press release. “Protected areas are very useful conservation tools, but unfortunately, the steep continuing rate of biodiversity loss signals the need to reassess our heavy reliance on this strategy.”

|

According to the authors focusing solely on protected areas for biodiversity preservation has a number of flaws. For one thing, society is still far from the minimum goal of conserving 30 percent of marine and terrestrial habitats in order to conserve global biodiversity. Currently 5.8 percent of land is under strict protection, while just 0.08 percent of the ocean is similarly protected. Not all protected areas are created equal. Many allow a number of destructive, unsustainable activities within their boundaries. In addition, most terrestrial protected areas (60 percent) are simply too small—less than 1 square kilometer—to save big or migrating species. Most protected areas are not well-connected in order to allow movement of animal and plant populations, especially in the face of worsening climate change.

Protected areas also do not combat all threats to species. While they help buffer species from habitat loss and overexploitation, they do little to save species from other impacts such as climate change, pollution, and invasive species.

Finally, governments have left most protected areas with too little money for management. According to the study, globally protected areas are underfunded to the tune of $18 billion a year: three times as much as is currently spent on managing protected areas ($6 billion). Poor management opens the door to any number of human impacts including poaching, illegal logging, habitat destruction, illegal fishing, etc. Lack of funding, poor management, and corruption means many protected areas are simply ‘paper parks’, protected by law, but systematically eroded by impacts.

“We’re definitely not saying we shouldn’t protect areas—the problem is that we’re investing all our human capital into those areas,” co-author Camilo Mora of University of Hawaii at Manoa told the BBC. “We’re putting all our eggs in one basket, which is dangerous; but even more dangerous is that there’s a hole in the bottom of the basket.”

The future is also precarious for many of the world’s protected areas. As human population grows—to seven billion this year, and a projected nine billion by 2035—and demand for resources grows, its likely governments will turn more and more to attacking protected areas for resources. Already, this trend is visible in a number of countries. Tanzania is pushing to downsize Selous Game Reserve for uranium mining. Cambodia is handing over 50,000 hectares of Viracehy National Park to rubber plantations and other development projects, essentially shrinking the protected area by 16%. Controversial roads, which can bring a number of adverse impacts, are being planned through protected areas in the Serengeti, in Laos, Vietnam, and in Sumatra. The US has been debating for decades to downgrade the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) to allow oil drilling. To date the refuge is safe, but the issue is likely to come up again. As the cost of food rises, there is also likely to be increased conflict between agricultural land and protected areas. One cannot depend on protected areas today surviving in the same form tomorrow.

An unidentified butterfly in Indonesian Borneo. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

According to the paper, the real issues that must be dealt with to prevent a mass extinction are human population and overconsumption. Humans now impact over 80 percent of the world’s land and 100 percent of the oceans. Around 40 percent of the Earth’s surface has been ‘strongly affected’ by our consumption.

“The explosive growth in the world’s human population in the last century has led to an increasing demand on the Earth’s ecological resources and a rapid decline in biodiversity. According to recent estimates, about 1.2 Earths would be required to support the different demands of the 5.9 billion people living on the planet in 1999. This ‘excess’ use of the Earth’s resources or ‘overshoot’ is possible because resources can be harvested faster than they can be replaced and because waste can accumulate (e.g. atmospheric CO2),” reads the paper.

Along this line, the authors conclude that if global society continues down the road we are on, we will need 27 planet Earths to sustain our consumption by 2050.

The authors don’t provide detailed solutions in their paper, but write that society must prioritize “alternative solutions targeting

human demand for ecological goods and services,

while ensuring human welfare.”

They add: “In our view, the only scenario to achieve sustainability […] will require a concerted effort to reduce human population growth and consumption and simultaneously increase the Earth’s biocapacity through the transference of technology to increase agricultural and aquacultural productivity.”

In fact, Mora told Aljazeera that in the future the situation could become so dire as to require ‘one child per woman’.

“I’m from Colombia, it blows my mind that some governments in the developing world pay women to have more children,” Mora added.

The authors argue that booming human population isn’t just a problem for the world’s species, but for people alike. Growing human populations is likely to lead to worsening shortages in food and water, declines in education, more competition for jobs, and spreading diseases. Global quality of life looks likely to be a casualty of more and more people.

A black-and-white ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata) in Madagascar. Their population has dropped by 80% in 27 years. This species is listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

“Apart from continuous [population] growth being ecologically

untenable, the negative economic effects of population

growth need greater recognition,” they write, in essence warning that the human population is set to overshoot its capacity to care for itself on a finite planet. Unless large-scale changes are made, biodiversity will be just one victim of the process.

“I don’t have a solution—I have struggled for some time trying to think what is the way to get people to realize how important this is—but if we don’t find it soon, the future is a very grim one,” Sale told the BBC. “We’re talking about losing 50 percent of species in the next half century—that’s faster than any previous mass extinction event—and anybody who thinks we can go through a mass extinction and be perfectly fine is just deluding themselves.”

Mora adds in a press release that “biodiversity is humanity’s life-support system, delivering everything from food, to clean water and air, to recreation and tourism, to novel chemicals that drive our advanced civilization.”

CITATION: Camilo Mora and Peter F. Sale. Ongoing global biodiversity loss and the need

to move beyond protected areas: a review of the

technical and practical shortcomings of protected

areas on land and sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series. Vol. 434: 251–266, 2011

doi: 10.3354/meps09214.

Related articles

Goodbye national parks: when ‘eternal’ protected areas come under attack

(03/17/2011) One of the major tenets behind the creation of a national park, or other protected area, is that it will not fade, but remain in essence beyond the pressures of human society, enjoyed by current generations while being preserved for future ones. The protected area is a gift, in a way, handed from one wise generation to the next. However, in the real world, dominated by short-term thinking, government protected areas are not ‘inalienable’, as Abraham Lincoln dubbed one of the first; but face being shrunk, losing legal protection, or in some cases abolished altogether. A first of its kind study, published in Conservation Letters, recorded 89 instances in 27 countries of protected areas being downsized (shrunk), downgraded (decrease in legal protections), and degazetted (abolished) since 1900. Referred to by the authors as PADDD (protected areas downgraded, downsized, or degazetted), the trend has been little studied despite its large impact on conservation efforts.

Decline in top predators and megafauna ‘humankind’s most pervasive influence on nature’

(07/14/2011) Worldwide wolf populations have dropped around 99 percent from historic populations. Lion populations have fallen from 450,000 to 20,000 in 50 years. Three subspecies of tiger went extinct in the 20th Century. Overfishing and finning has cut some shark populations down by 90 percent in just a few decades. Though humpback whales have rebounded since whaling was banned, they are still far from historic numbers. While some humans have mourned such statistics as an aesthetic loss, scientists now say these declines have a far greater impact on humans than just the vanishing of iconic animals. The almost wholesale destruction of top predators—such as sharks, wolves, and big cats—has drastically altered the world’s ecosystems, according to a new review study in Science. Although researchers have long known that the decline of animals at the top of food chain, including big herbivores and omnivores, affects ecosystems through what is known as ‘trophic cascade’, studies over the past few decades are only beginning to reveal the extent to which these animals maintain healthy environments, preserve biodiversity, and improve nature’s productivity.

Climate change to push over 10 percent of the world’s species to extinction by 2100

(07/11/2011) Scientists have predicted for decades that climate change could have a grave impact on life on Earth, which is already facing numerous threats from habitat loss, over-exploitation, pollution, invasive species, and other impacts. However, empirical proof of extinctions–and even endangerment–due to climate change have been difficult to come by. A new study in the Proceeding of the National Academy of Science has found that by the time today’s infants are 90 years old (i.e. the year 2100) climate change could have pushed over 11 percent of the world’s species to extinction.

Ocean prognosis: mass extinction

(06/20/2011) Multiple and converging human impacts on the world’s oceans are putting marine species at risk of a mass extinction not seen for millions of years, according to a panel of oceanic experts. The bleak assessment finds that the world’s oceans are in a significantly worse state than has been widely recognized, although past reports of this nature have hardly been uplifting. The panel, organized by the International Program on the State of the Ocean (IPSO), found that overfishing, pollution, and climate change are synergistically pummeling oceanic ecosystems in ways not seen during human history. Still, the scientists believe that there is time to turn things around if society recognizes the need to change.

Over 900 species added to endangered list during past year

(06/16/2011) The past twelve months have seen 914 species added to the threatened list by the world’s authority of species endangerment, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s Red List. Over 19,000 species are now classified in one of three threatened categories, i.e. Vulnerable, Endangered, and Critically Endangered, a jump of 8,219 species since 2000. Species are added to the threatened list for a variety of reasons: for many this year was the first time they were evaluated, for others new information was discovered about their plight, and for some their situation in the wild simply deteriorated. While scientists have described nearly 2 million species, the IUCN Red List has evaluated only around 3 percent of these.

South Sudan’s choice: resource curse or wild wonder?

(07/11/2011) After the people of South Sudan have voted overwhelmingly for independence, the work of building a nation begins. Set to become the world’s newest country on July 9th of this year, one of many tasks facing the nation’s nascent leaders is the conservation of its stunning wildlife. In 2007, following two decades of brutal civil war, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) surveyed South Sudan. What they found surprised everyone: 1.3 million white-eared kob, tiang (or topi) antelope and Mongalla gazelle still roamed the plains, making up the world’s second largest migration after the Serengeti. The civil war had not, as expected, largely diminished the Sudan’s great wildernesses, which are also inhabited by buffalo, giraffe, lion, bongo, chimpanzee, and some 8,000 elephants. However, with new nationhood comes tough decisions and new pressures. Multi-national companies seeking to exploit the nation’s vast natural resources are expected to arrive in South Sudan, tempting them with promises of development and economic growth, promises that have proven uneven at best across Africa.

(06/12/2011) While few would question that conserving a certain percentage of land or water is good for society overall, it has long been believed that protected areas economically impoverish, rather than enrich, communities living adjacent to them. Many communities worldwide have protested against the establishment of conservation areas near them, fearing that less access and increased regulations would imperil their livelihoods. However, a surprising study overturns the common wisdom: showing that, at least in Thailand and Costa Rica, protected areas actually boost local economies and decrease poverty.

Brazil protected areas suffer serious deficiencies, says study

(05/25/2011) Brazil’s conservation units are poorly run and in need of better funding, finds a new study published by Brazil’s Ministry of the Environment and the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). The assessment, released last week, concludes Brazil’s protected areas system should be open to creative management solutions.

With pressure to drill, what should be saved in the Arctic?

(04/27/2011) Two major threats face the Arctic: the first is global climate change, which is warming the Arctic twice as fast the global average; the second is industrial expansion into untouched areas. The oil industry is exploring new areas in the Arctic, which they could not have reached before without anthropogenic climate change melting the region’s summer ice; but, of course, the Arctic wouldn’t be warming without a hundred years of massive emissions from this very same industry, thus creating a positive feedback loop that is likely to wholly transform the Arctic.

Protected areas cover 44% of the Brazilian Amazon

(04/20/2011) Protected areas now cover nearly 44 percent of the Amazon — an area larger than Greenland — but suffer from encroachment and poor management, reports a new study by Imazon and the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). The report, published in Portuguese, says that by December 2010, protected areas in the Brazilian Amazon amounted to 2,197,485 square kilometers. Conservation units like national parks accounted for just over half the area (50.6 percent), while indigenous territories represented 49.4 percent.

(04/14/2011) What’s happening in Tanzania? This is a question making the rounds in conservation and environmental circles. Why is a nation that has so much invested in its wild lands and wild animals willing to pursue projects that appear destined not only to wreak havoc on the East African nation’s world-famous wildlife and ecosystems, but to cripple its economically-important tourism industry? The most well known example is the proposed road bisecting Serengeti National Park, which scientists, conservationists, the UN, and foreign governments alike have condemned. But there are other concerns among conservationists, including the fast-tracking of soda ash mining in East Africa’s most important breeding ground for millions of lesser flamingo, and the recent announcement to nullify an application for UNESCO Heritage Status for a portion of Tanzania’s Eastern Arc Mountains, a threatened forest rich in species found no-where else. According to President Jakaya Kikwete, Tanzania is simply trying to provide for its poorest citizens (such as communities near the Serengeti and the Eastern Arc Mountains) while pursuing western-style industrial development.