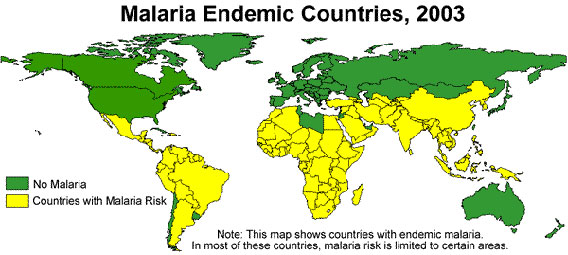

Map courtesy of the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Scientists predict that malaria could spread further with climate change.

In 2009, 781,000 people died of malaria worldwide and nearly a quarter billion people contracted the mosquito-bourne disease, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). While the impacts of malaria on people—among the world’s worst diseases—have long been researched, a new study in Biological Conservation finds that malaria has a significant indirect impact on protected species. Many species contract various malaria strains, but the study also found that malaria in humans has the potential to leave endangered species unprotected.

“In places where malaria is prevalent, it sickens and even kills some park guards who are attempting to limit wildlife poaching. For instance at Pakke Tiger Reserve in India, our study revealed that 70 percent of 144 park guards contracted malaria over a four-year period,” Dr. William F. Laurance, an ecologist at James Cook University and co-author of the study, explained to mongabay.com. “Malaria makes the guards too sick to do their jobs.”

Sick guards mean less protection for Pakke’s wildlife, such as the Bengal tiger. Located in remote northeastern India, Pakke Tiger Reserve is in the heart of malaria territory. According to the study, five out of a thousand people in the region become sick with malaria annually, more than double India’s overall rate.

Malaria also has an economic impact on Pakke Tiger Reserve: sick staff members eat up limited conservation funds even though India’s health service is supposed to provide healthcare for all malaria cases.

Anopheles albimanus, a common carrier of malaria. Photo courtesy of the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). |

“[Pakke Tiger Reserve] had to spend around 3 percent of its limited budget to help treat or replace its sick guards,”says Laurance, who adds that even with aid from the forest service, many staff members pay a significant portion of their salary for out of pocket treatment.

Malaria hits Pakke Tiger Reserve hardest during the monsoon season, and the researchers think this coincides with criminals stepping up their poaching efforts.

“There is preliminary evidence to suggest that poachers prefer hunting during the monsoons as animals can be approached from close quarters

and poachers can more easily avoid detection as they make very little noise while hiking on wet leaf litter,” lead author Nandini Velho, a doctoral student at James Cook University in Australia and research associate at National Center for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bangalore, told mongabay.com.

With more forest guards out sick during the monsoon, it is likely that poachers have an easier time getting away with their quarry.

It doesn’t have to be this way argue the authors. Simple mitigation efforts—such as mosquito nets treated with insecticide—can keep staff healthier, save funds for other uses, and better protect wildlife. The recommendation aren’t theoretic. With the help of Indian-company Sumitomo Chemicals, researchers distributed insecticide mosquito nets to all forest guards and anti-poaching camps in Pakke Tiger Reserve. The results? In one year, malaria rates fell by eight to ten-fold.

“Prevention is indeed better than cure,” Velho said in a press release. “Not only is it cheaper and often easier to implement, it also means that fewer families will suffer from disease or death.”

However, despite the success of such simple measures and government promises, many people in India and elsewhere remain left behind in the fight against malaria.

“Drugs still don’t reach remote areas, and doctors are still not provided enough of incentives to stay in these areas. The success of the malaria eradication program has been limited by the lack of facilities and trained staff in remote areas,” Velho told mongabay.com.

Laurance adds that if malaria is making it easier to poach animals in northeast India, it is likely hampering conservation efforts in many parts of the world.

“This almost certainly isn’t a problem limited to India. Malaria is a global scourge, particularly in many tropical and poorer nations.

Cerebral malaria, which kills many of those infected, is prevalent across much of the tropical world—from Africa to India and Papua New

Guinea, and in many nations in between.”

In India the researchers recommend that the forest and health services work together to combat this issue, since both institutions have a stake in mitigating and treating malaria.

CITATION: Nandini Velho, Umesh Srinivasan, Prashanth N.S. & William F. Laurance (2011) Human disease hinders anti-poaching efforts in Indian nature reserves. Biological Conservation, in press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.06.003.

Related articles

Malaria increases 50 percent following deforestation in the Amazon

(06/16/2010) A new study shows that deforestation in the Amazon helps spread disease by creating an optimal environment for malaria-carrying mosquitoes. The study, published in the online issue of the CDC journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, found that clearing forests in the Brazilian Amazon raised incidences of malaria by almost 50 percent.

Tropical forest tree is source of new mosquito repellent as effective as DEET

(02/05/2009) Isolongifolenone, a natural compound found in the Tauroniro tree (Humiria balsamifera) of South America, has been identified as an effective deterrent of mosquitoes and ticks, report researchers writing in the latest issue of Journal of Medical Entomology.

Global malaria map released – 35% of humanity at risk

(02/25/2008) Researchers have developed a spatial distribution map for malaria. The results are published in Public Library of Science (PLoS) Medicine.