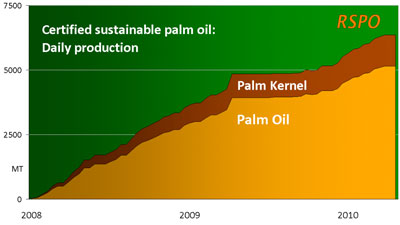

The Netherlands has committed to only using palm oil certified under the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) by 2015, providing a huge boost for the certification standard which aims to improve the social and environmental performance of the world’s most productive oil crop. The pledge makes the Netherlands the first country to commit itself to using only sustainable palm oil.

“Dutch business has long been closely involved in efforts to make the palm oil supply chain more sustainable. The country has been one of the front runners in this respect,” said Frans Claassen, Director of the Dutch Product Board for Margarine, Fats and Oils (MVO). “Now, we commit ourselves to acting on our believes. Over the next few years, we will work very hard to ensure that all palm oil used in the Netherlands will be sustainable by the end of 2015. In other words, that it is purchased in accordance with one of the trading systems approved by the RSPO.”

Click to enlarge |

“We call on other countries in Europe, North America and Asia to follow this example.”

The Netherlands is Europe’s largest trader of palm oil, importing and exporting nearly 2.5 million metric tons in 2007. Much of the palm oil goes into products sold in other European countries.

The commitment, which was presented today to Henk Bleker, Dutch Minister of Agriculture and Foreign Trade, as a manifesto [PDF], comes under the Dutch Taskforce Sustainable Palm Oil, a group that includes associations representing the Dutch refining industry, food manufacturing industry and feed industry. The taskforce was initiated by the MVO, which participates in the RSPO.

In a statement, Bleker commended the move.

Palm oil plantation in Sumatra. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

“The Task Force is a very good initiative that shows everyone can take responsibility,” he said. “We will all benefit from sustainable palm oil, so this is good news for palm oil producers, for palm oil traders, and for Dutch consumers as well.”

Palm oil

Global palm oil consumption stands at nearly 50 million tons per year, about half of which is traded internationally. It is used widely in processed foods, cosmetics, and soaps — WWF estimates that palm oil is found in roughly half of packaged supermarket products. It is also increasingly used as a biofuel.

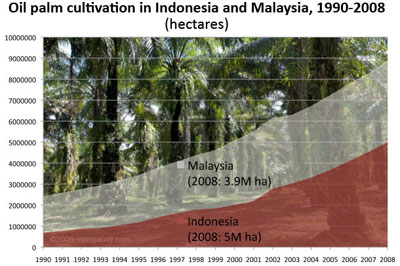

But while palm oil is a highly efficient crop, surging production over the past 20 years has spurred strong backlash from environmentalists who note its expansion has consumed vast areas of rainforest in Malaysia and Indonesia, triggering substantial greenhouse gas emissions and putting endangered wildlife—including orangutans, pygmy elephants, Sumatran rhinos and tigers—at risk. Oil palm plantation development has also exacerbated social conflict in some areas.

|

The RSPO emerged as a response to these concerns. The body—which includes industry stakeholders as well as environmentalists and other groups—sets sustainability criteria for palm oil production. Nevertheless the initiative has been battered over the past year with revelations that some members have continued to destroy ecologically sensitive habitats. Prominent members, including Unilever and Nestle, have had to act outside the RSPO process to address misconduct by RSPO-member suppliers. Some critics say the scheme lacks oversight, sets a low bar for compliance, and is underfunded. Supporters argue that RSPO is still a relatively new initiative that needs more time to prove itself. The RSPO recently censured a member—PT SMART—which had failed to comply with the body’s rules. SMART, which has lost a number of major clients including Unilever, Kraft, Burger King, and Nestle, is now working to clean up its operations.

Related articles

Misleading claims from a palm oil lobbyist

(10/23/2010) In an editorial published October 9th in the New Straits Times (“Why does World Bank hate palm oil?”), Alan Oxley, a former Australian diplomat who now serves as a lobbyist for logging and plantation companies, makes erroneous claims in his case against the World Bank and the International Finance Corp (IFC) for establishing stronger social and environmental criteria for lending to palm oil companies. It is important to put Mr. Oxley’s editorial in the context of his broader efforts to reduce protections for rural communities and the environment.

Corporations, conservation, and the green movement

(10/21/2010) The image of rainforests being torn down by giant bulldozers, felled by chainsaw-wielding loggers, and torched by large-scale developers has never been more poignant. Corporations have today replaced small-scale farmers as the prime drivers of deforestation, a shift that has critical implications for conservation. Until recently deforestation has been driven mostly by poverty—poor people in developing countries clearing forests or depleting other natural resources as they struggle to feed their families. Government policies in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s had a multiplier effect, subsidizing agricultural expansion through low-interest loans, infrastructure projects, and ambitious colonization schemes, especially in the Amazon and Indonesia. But over the past two decades, this has changed in many countries due to rural depopulation, a decline in state-sponsored development projects, the rise of globalized financial markets, and a worldwide commodity boom. Deforestation, overfishing, and other forms of environmental degradation are now primarily the result of corporations feeding demand from international consumers. While industrial actors exploit resources more efficiently and cause widespread environmental damage, they also are more sensitive to pressure from consumers and environmental groups. Thus in recent years, it has become easier—and more ethical—for green groups to go after corporations than after poor farmers.

The Nestlé example: how responsible companies could end deforestation

(10/06/2010) The NGO, The Forest Trust (TFT), made international headlines this year after food giant Nestlé chose them to monitor their sustainability efforts. Nestlé’s move followed a Greenpeace campaign that blew-up into a blistering free-for-all on social media sites. For months Nestle was dogged online not just for sourcing palm oil connected to deforestation in Southeast Asia—the focus of Greenpeace’s campaign—but for a litany of perceived social and environmental abuses and Nestlé’s reactions, which veered from draconian to clumsy to stonily silent. The announcement on May 17th that Nestlé was bending to demands to rid its products of deforestation quickly quelled the storm. Behind the scenes, Nestlé and TFT had been meeting for a number of weeks before the partnership was made official. But can TFT ensure consumers that Nestlé is truly moving forward on cutting deforestation from all of its products?

Nestle’s palm oil debacle highlights current limitations of certification scheme

(03/26/2010) Last week Nestle, the world’s largest food processor, was caught in a firestorm when it attempted to censor a Greenpeace campaign that targeted its use of palm oil sourced from a supplier accused of environmentally-damaging practices. The incident brought the increasingly raucous debate over palm oil into the spotlight and renewed questions over an industry-backed certification scheme that aims to improve the crop’s environmental performance.

Consumers should help pay the bill for ‘greener’ palm oil

(01/12/2010) Palm oil is one of the world’s most traded and versatile agricultural commodities. It can be used as edible vegetable oil, industrial lubricant, raw material in cosmetic and skincare products and feedstock for biofuel production. Growing global demand for palm oil and the ensuing cropland expansion has been blamed for a wide range of environmental ills, including tropical deforestation, peatland degradation, biodiversity loss and CO2 emissions. In response to these concerns, a group of stakeholders—including activists, investors, producers and retailers—formed the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to develop a certification scheme for palm oil produced through environmentally- and socially-responsible ways. It is widely anticipated that the creation of a premium market for RSPO-certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) would incentivize palm oil producers to improve their management practices.