Conservationists work with local communities to protect the okapi, and its rainforest habitat, in the aftermath of a brutal civil war.

The giraffe is one of Africa’s most recognizable animals, but its shy and elusive forest cousin, the okapi, was so little known that until just over a century ago the western world believed it was a mythical beast, an African unicorn.

Today, a shroud of mystery still envelops the okapi, an animal that looks like a cross between a zebra, a donkey, and a giraffe. But what is known is cause for concern. Its habitat, long protected by its remoteness, was the site of horrific civil strife, with disease, famine, and conflict claiming untold numbers of Congolese over the past decade. Now, as a semblance of peace has settled over Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the okapi’s prospects have further dimmed, for its home is increasingly seen as a rich source of timber, minerals, and meat to help the war-torn country rebuild.

John Lukas with Mbuti pygmies on the bank of the Epulu River in Democratic Republic of Congo |

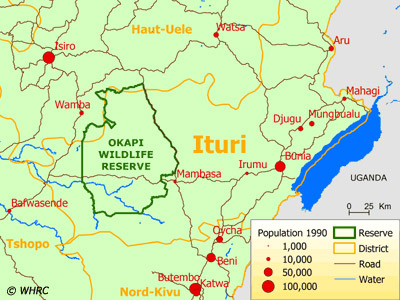

In an effort to ensure that the okapi does not become a victim of economic recovery, the Okapi Conservation Project (OCP) is working to protect the okapi and its habitat. Founded by John Lukas in 1987, well before the conflict, OCP today manages the Okapi Wildlife Reserve, a 13,700-square-kilometer tract of wilderness in the Ituri Forest of northeastern DRC. While OCP trains and equips wildlife rangers, using traditional approaches and cutting-edge technology, it realizes that guards and protected areas alone will not save the okapi, especially in a region where people struggle to provide for their families. Thus OCP provides assistance to improve the lives of neighboring communities, including support to develop sustainable incomes from agroforestry and alternative sources of protein to reduce bushmeat hunting. Further, OCP has worked with local authorities to track and close down illegal mines and logging operations.

Okapi. Courtesy of the Okapi Conservation Project. |

But the group is also working on ex-situ conservation measures, including a captive breeding program for okapi living in zoos and other facilities around the world. The effort is headquartered at the White Oak Conservation Center in northern Florida. The center, established in 1982 by philanthropist Howard Gilman, covers 600 acres and is surrounded by 6,800 acres of pine and hardwood forest and wetlands.

John Lukas, an ungulate specialist who founded the Okapi Conservation Project, says the efforts of OCP and the White Oak Conservation Center have helped protect 4,000 to 6,000 okapi, as well as numerous other plant and animal species, in the Okapi Wildlife Reserve. The project has simultaneously raised awareness about the plight of the Congo forest and its people, while helping local communities benefit from sustainable forest use.

Lukas talked about the okapi and OCP’s conservation initiatives during an August 2009 interview with mongabay.com. Lukas will be presenting at the upcoming Wildlife Conservation Network Expo in San Francisco on October 3rd.

AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN LUKAS

Mongabay: What is your background and how did you get interested in working on the Okapi?

John Lukas with an okapi at the OCP’s research and breeding station in Epulu DRC. |

John Lukas: I have a background in Zoology and worked for the New York Zoological Society (presently Wildlife Conservation Society) for 6 years before coming to work for Howard Gilman in 1982 to develop the White Oak Conservation Center (WOCC). Part of our mission at WOCC is to support efforts in range states that benefit the species we maintain at WOCC. I felt the resources that we have at White Oak – space, privacy, and semi-tropical climate – would really benefit okapi. In the middle 1980s okapi populations in captivity were declining rapidly and there was not one area in Africa dedicated to protecting habitat where okapi occurred. We developed a strategy to build the best facility in the world to breed and properly care for okapi and at the same time undertake a multifaceted effort to secure a protected area for okapi, develop a breeding and research station in the middle of okapi habitat and build a talented team of Congolese which could protect okapi and run the research station.

John Lukas with an okapi at the OCP’s research and breeding station in Epulu DRC.

|

My personal interest has always been ungulates (I am also President of the International Rhino Foundation) and the okapi are highly unusual. Very little was known about them and they were in need of help as their habitat was being encroached upon and developed by the expanding and migrating population of war torn Central Africa. They are silent creatures that cannot exist without intact forests and they depend entirely on human intervention to stop the loss of the remarkable forests of the Congo basin. As a flagship species protecting okapi maximizes conservation efforts and dollars, securing habitat and protection for all the elephants, chimpanzees, birds, antelope, primates and millions of plant and animal species found in the Ituri ecosystem.

On a personal level, touching their velvet like hair and looking into their deep dark eyes moves me to help an animal that cannot speak for itself.

Mongabay: There is still much to be learned about the okapi – what are presently the major areas of research on the species?

|

John Lukas: The okapi project is currently developing okapi research projects in several areas. To enhance the okapi breeding program we are developing assisted reproduction techniques such as semen collection and freezing, and artificial insemination. While assisted reproduction is common in domestic species, these techniques have never been developed in the okapi. This ground breaking work will allow us to more easily move and store okapi gametes as a genetic “bank” for the species. If international protocols can be developed these tools can be used to more easily link populations of okapi and produce genetically healthy animals to enhance populations.

We are also working with Dr. Mike Bruford’s genetics lab at Cardiff University to develop micro satellite genetic markers for the okapi. This information will be extremely important for the okapi’s future in the Democratic Republic of Congo; as more forest is lost okapi populations are becoming increasingly fragmented. With these “tools” the genetic makeup of specific okapi populations can be assessed and compared, to better understand the relationship between okapi populations, and to provide valuable information for future okapi management in the DR Congo.

We have released okapi from our research station and have documented their resettlement in the wild. We have had two Mbuti pygmies follow one male for over three years giving us insight into the leaves they eat, their home range, and the various parasites they encounter in upland forest habitat.

Mongabay: What role does the White Oak Conservation Center play in okapi conservation?

Map showing the Okapi Wildlife Reserve. |

John Lukas: White Oak Conservation Center has been active with okapi conservation in the DR Congo for 22 years, operating the Okapi Conservation Project through our non-profit arm Gilman International Conservation Foundation. Many consider the Conservation Center as the okapi center of excellence, because of our specialized managed okapi facilities which currently hold 17 okapi, and because we work closely with our zoo colleagues around the world who hold and breed okapi. With our international zoo partners White Oak Conservation Center raises nearly $750,000 per year and operates the Okapi Project located in the Ituri Forest of the DR Congo. The Project’s main objective is to sustain the 13,760 sq. km Okapi Wildlife Reserve through our partnership with the Institute in Congo for the Conservation of Nature. The lowland forest Okapi Wildlife Reserve is home to 4000-6000 okapi and numerous wildlife and plant species, one of the most diverse forests in Central Africa. In addition to support for ICCN to protect the Reserve, the Project operates conservation education, agro-forestry, and alternatives to bushmeat programs working with communities around the Reserve.

Mongabay: Did the conflict in DRC take much of a toll on okapi? Is it known if they were hunted during the strife? How did your workers and partners fare?

John Lukas: The civil conflicts over the last decade have taken a great toll on the county and people of the DR Congo. The Ituri Forest was not excluded and in fact the battle lines included Project headquarters, and our equipment and vehicles were looted and stolen, our staff harassed and beaten. Incredibly, and to their credit, the Project staff stayed in the area and continued to work for the conservation of the okapi throughout the conflict. Because of their presence there are still significant numbers of okapi found in the Okapi Wildlife Reserve, however surveys conducted after the conflict suggest that wildlife numbers have decreased compared with surveys prior to the war, so there was probably an impact on the okapi population. Nevertheless, we could only document the killing of only 4 to 5 okapi over the last 5 years.

Mongabay: What is currently the biggest threat to the okapi?

Gold mining. |

John Lukas: The loss of the forest and its natural resources is the largest threat to the okapi as more and more people move into the Ituri Forest because of the stress and conflicts in Eastern DR Congo. The forest is rich in trees, gold, diamonds, and coltan ore and in some people’s minds, represents untapped wealth. Despite the protected area status of the Okapi Wildlife Reserve, the forest faces significant threats from artisanal logging, slash and burn agriculture, mining, and bushmeat hunting.

Mongabay: Is it difficult to convince local communities who have suffered so much over the past decade to care about the okapi?

John with the Mbuti pygmies that collect leaves for the okapi, after receiving new t-shirts. |

John Lukas: As anywhere in the world, the people of the Ituri Forest wish to feed, clothe, and provide health care for their families, and to educate their children. The conflicts in the DR Congo challenged many families’ ability to provide even these basic needs. The Okapi Project education and agro-forestry team’s work with the communities to provide them with information, technical assistance, and resources to create an understanding of the importance of the okapi and the Okapi Wildlife Reserve while helping them improve their livelihoods, directly linking community benefits to okapi conservation. Improving people’s understanding of the value of natural systems to their own survival is a major focus of the Okapi Conservation Project.

Mongabay: What are the biggest challenges of working in DRC?

OWR warden and rangers.

|

John Lukas: Although there have been positive changes in the DRC in the past few years, the lack of infrastructure such as transportation, utilities, schools, and health care are our biggest challenges. The Project could better focus its efforts on wildlife conservation if not that it must first work to provide assistance and improve living conditions for the people living around and in the Reserve in order to change people’s relationship with the land and wildlife to be more sustainable.

Mongabay: What is needed to secure the future for Okapi?

John Lukas: The historic range of the okapi has already been significantly fragmented by the loss of forest and despite securing the Okapi Wildlife Reserve, which represents only one strong okapi population, the DR Congo needs to understand the importance of the species diversity contained within their incredible block of forest, as they begin to expand the commercial exploitation of their natural resources. With proper and sustainable forest management, which sets aside valuable protected areas and provides funding for their management and protection, the endemic wildlife like the okapi, bonobo, the Congo peacock and the Eastern lowland gorilla and their habitats, can be assured well into the future.

Mongabay: Do you see any potential for payments for ecosystem services, such as REDD, to help fund conservation efforts?

John Lukas: Incentives for protecting and replanting forests can only help conservation organizations, and ultimately countries like the DRC which have valuable existing carbon sinks, to financially benefit from their forests, and forest restoration and conservation. Out belief is that if the forests are protected, we can conserve the wildlife, whether rhino living in Sumatra or okapi in the DRC.

Mongabay: How can people in places like the US help okapi conservation?

|

John Lukas: We certainly welcome anyone to help support White Oak Conservation Center and the Okapi Conservation Project. They can also visit and support their local zoo which keeps okapi and partners with the Okapi Conservation Project. Supporting conservation organizations working to protect the forests and wildlife of the DRC is also beneficial. Urging US policy makers to take a stronger stand to control climate change will eventually benefit forest and okapi.

Mongabay: Do you have any tips for aspiring field conservationists?

John Lukas: Get a good education, follow your passion, remain committed at all cost, and remember that wildlife conservation is about people – their understanding of the issues and their resulting actions.

John Lukas will be presenting at the upcoming Wildlife Conservation Network Expo in San Francisco on October 3rd

Related articles

Rare okapi photographed for the first time in Congo park

(09/10/2008) A camera trap has captured the first-ever photo of an okapi in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Virunga National Park. The picture shows that the elusive forest giraffe has managed to survive more than a decade of war in and around the park.

Okapi, other wildlife saved in the Congo by forest protector

(04/21/2005) Corneille Ewango of the Wildlife conservation Society today received the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize for risking his life helping to protect one of Africa’s environmental gems—the Okapi Faunal Reserve—from the depredations of rebel militias in the wartorn region of the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.