When Crisis Begets Crisis

Despite the popularity he enjoyed abroad, domestic support for ousted president Marc Ravalomanana eroded rather quickly last February when he went head to head with Andry Rajoelina, the rookie mayor of Madagascar’s capital. The upset began last December when Ravalomanana closed down Rajoelina’s Viva TV for broadcasting an interview with his own predecessor and rival, Didier Ratsiraka. Rajoelina quickly shot back with criticisms of the president’s lavish personal spending and deal-making with foreign governments. Adding a host of populist grievances to his own, Rajoelina rallied disparate opposition groups to the cause and soon toppled the incumbent to become, at his own proclamation, President of the “High Authority of Transition.”

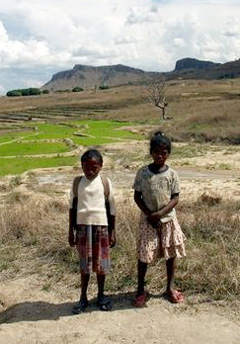

Half of Madagascar’s children under five years of age are malnourished. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

For the country as a whole, the results have not been encouraging. Despite his promises to bring transparency and genuine democracy to Madagascar, Rajoelina has stifled protests, closed opposition media outlets and set elections for October 2010, just four months before they were originally scheduled to take place. The tourism industry has shriveled to a shadow of itself, important donors including the American government and the IMF have suspended non-humanitarian aid, and a power vacuum has set in in remote regions of the island, wreaking havoc on some of its most fragile and prized ecosystems. In response, conservation groups and Western governments have come together to condemn the surge in illegal logging in Madagascar’s northern forests and poaching of endangered species there.

The statement, signed by the US, Norway, France, and the World Bank, among others, is hard not to read cynically. It calls for action on the part of a government which none of the signatories recognizes as legitimate, and whose shoestring budget (which cannot even fund schools and hospitals nationally) is historically comprised of 70% foreign aid, most of which has been suspended since February. What, really, do they expect the government to do? A Malagasy friend of mine who works in agricultural development there joked to me in his office that “Americans won’t work anywhere where there isn’t forest.” His implication was that American development work is clustered around areas of high interest to conservation groups to the exclusion of other places where the need is just as urgent. The damage of the past few months demonstrates that long-term conservation success depends on the overall political stability of a country and in turn on the steady improvement of the lives of its citizens. Even more importantly, it relies on the reduction of consumer demand for ‘forest products’ in wealthy countries, and on the political will to bring this about through tariffs, import bans, and legislation on sourcing and traceability.

One of Ravalomanana’s most widely touted successes as president was to triple the reach of protected areas in Madagascar, to some 10% of the remaining forests on the island, which in turn comprise something like 10% of what once was. Conservationists now say that years, even decades of successful conservation work are being undone by the organized mafia pillaging Marojejy and Masoala national parks for rosewood and ebony. But we mustn’t feign surprise.

Illegal rosewood logging in northeastern Madagascar.

|

Political stability is the sine qua non of environmental preservation; as nobel laureate Wangari Maathai has it, “responsible governance of the environment [is] impossible without democratic space.” Short of totalitarian rule, even stability is not enough without good governance and genuine measures to fight poverty (Zimbabwe is a case in point). Was it premature, then, to congratulate Ravalomanana on his conservation initiatives when all signs showed that this democratically-elected leader was not, in fact, a strong promoter of democracy? His government played host to conservation efforts that slowed the horrible deforestation which characterized the reign of his predecessor, but logging and smuggling by the political elite never stopped, nor did they need to operate far under the radar. Though Madagascar’s economy grew by more than five percent each year Ravalomanana was in power, he did little to reduce poverty, and purchasing power actually slipped. According to Reporters Without Borders, journalistic freedom in Madagascar plummeted from 65th to 95th in the world during Ravalomanana’s tenure. Using the State as a foil, the President expropriated land from peasant farmers for his own business interests, awarded his companies lucrative government contracts, and changed tax laws to import his companies’ equipment tariff-free, losing vital streams of government revenue in a country where the government can barely pay its employees. It was not until January of this year that the IMF began to scrutinize Ravalomanana’s budget and demand an explanation. They wondered whether the purchase of a $60 million presidential jet was in line with development goals in a country where 85% of the population lives on less $2 a day. But this was too little too late: the jet, dubbed “Air Force,” became a focal point for Rajoelina’s opposition.

The irony of the current situation is that despite the tremendous passion and excitement Madagascar’s natural beauty is apt to excite among Westerners, Western institutions are more or less bound to abandon conservation efforts there at a time when they are most vital. At least in part, they do so for good reason: where there is real risk to personnel and uncertain accountability for program funding, how effectively could international organizations remain in operation? Local populations have resisted the current wave of devastation to some extent, but there is little they can do to stand up to armed gangs backed by wealthy businessmen. With their vanilla crop at the mercy of cyclones and the global commodities market, many locals have also gone to work for smugglers identifying or hauling trees. There is a need for enforcement beyond what the locals can provide, and it must come from the port and from the consumers.

Baobab tree in a rice paddy in Madagascar. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

The parquets, musical instruments, and furniture that come from Malagasy forests will end up, in large part, in European and American homes, these majestic trees and vital habitats laundered successfully through Chinese ports and factories. Consumer demand is the ultimate driver of illegal logging. If we refuse to buy untraceable wooden products, if we support only companies with good and verifiable logging practices, we will need to pay more, but we will be paying the true cost of each item rather than passing it off to Madagascar.

At the level of government grants and international organizations, the situation in Madagascar begs us to reconsider how we think of conservation success. Locally, conservation groups are to be commended for doing inclusive grass roots work to preserve ecosystems. Still, there is nothing apolitical about conservation. As long as the American government funds conservation efforts with one hand while patting the back of leaders like Ravalomanana, conservation efforts are bound to fail in the long run. While research and direct investment in programming are both critical to conservation, neither is as important as helping to wrestle Madagascar from the cycle of corrupt governance and tumultuous transitions that has gripped it since independence in 1960. If that is to be accomplished, foreign governments and NGOs need to be serious about applying pressure in the right places–to improve accountability, transparency, and democratic institutions in the countries where they work. Ravalomanana cannot have been a good president to Madagascar’s natural world when he was not a good president to his people.

Rowan Moore Gerety is a writer living in Los Angeles. He was in Madagascar from October-December of 2008. He can be reached at “rowanmg [at] gmail [dot] com”