‘Snow leopard’ of the Andes is one of the world’s most endangered cats

‘Snow leopard’ of the Andes is one of the world’s most endangered cats:

An interview with Mauro Lucherini of the Andean Cat Alliance

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

September 29, 2008

One of the world’s rarest cats is also one of its least known.

The Andean mountain cat, sometimes called the “snow leopard” of the Andes, is an elusive species found only at high elevations of the Andean region in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile and Peru. Little is known about its ecology and behavior. While the species is known to be rare, no one knows how many individuals survive in the wild.

Mauro Lucherini and his colleagues at the Andean Cat Alliance (AGA) are working to change this. The Alliance — which spans the cat's range and involves more than two dozen researchers — is studying the species and carrying on awareness-raising and community participation activities so as to better protect it from the many threats it is believed to face. The work is not easy — studying the Andean mountain cat in its habitat is truly a challenge.

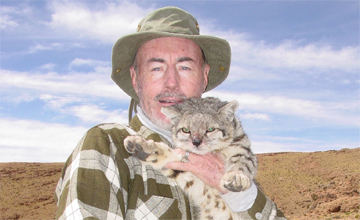

Mauro Lucherini in the Altiplano |

"Rarity is only one of the difficulties that you have to face if you want to track these cats," explained Lucherini in a September 2008 interview with mongabay.com. "In Argentina the Altiplano is huge and, in some cases, to reach the mountain ranges that are inhabited by cats you need a two-day 4×4 drive. Then you need to find a place where drinkable water is enough to set up a campsite. Finally, one needs to be fit enough to withstand the strong solar radiation after a freezing night, the constant winds that may easily turn into storms, and, especially, the lack of oxygen, which usually causes headaches and nausea for the first days."

Nevertheless Lucherini loves his work.

"The true measure of success in conservation field work is that you love being out there," he said. "Scientific curiosity may help and it will help if you enjoy sharing hard work with friends, but you need to be self-motivated and aware that the fruits of the seeds you plant are more likely to be tasted by your children than by yourself."

Andean Cat |

Lucherini and the AGA are partially supported by the Wildlife Conservation Network (WCN), an innovative group that uses a venture capital model to protect some of the world's most endangered species. WCN will be hosting Lucherini at its upcoming Wildlife Conservation Expo in San Francisco, California on October 4th. Expo attendees will be able to meet Lucherini and the Andean Cat Alliance firsthand. The event, which is open to the public at a cost of $25-50 per person, also features 16 other conservationists working to protect wildlife around the world.

AN INTERVIEW WITH MAURO LUCHERINI

Mongabay: What is your background and how did you get interested in working on the Andean cat?

Mauro Lucherini: That's a long story. I have always loved being in the field. And I always wanted to study carnivores, at least since the moment I was face to face with a red fox in Italy. I was an undergraduate student at University of Milan, Italy, then, and I decided to graduate with a final work on red fox ecology that enabled me to stay for one year in field and confirm my passion.

Mauro Lucherini in the Altiplano |

A few years later, while I was working on my PhD, I was offered a chance to take part in a couple of expeditions to the Andes in Argentina. That was the first time I heard of the Andean cat. The huge wilderness areas and the friendly people of Argentina caught my imagination and my curiosity. I moved to Argentina, with the initial idea of living here for 1 or 2 years, but I never left. By then, nobody had ever attempted to study the Andean cat and this looked like the greatest challenge of my life. Thus, as soon as I found someone willing to fund some work on the cat, my team started traveling to the high-altitude deserts of the Andes and found out what the challenge really meant! But this is another story….

Mongabay: How many people are involved with the Andean Cat Alliance?

Andean Cat Alliance |

Mauro Lucherini: AGA is a dynamic organization open to all conservationists, educators and researchers interested in working for the conservation of the High Andes wildlife. At the moment, AGA comprises some 25 South American members, almost equally distributed among Argentina, Bolivia, Chile and Peru, working in 10 teams, plus 3 international members (from USA and UK).

In addition, our activities involve a large number of university students, local teachers, rangers and other staff from Protected Areas, and villagers.

Mongabay: Does anyone know how many Andean cats survive in the wild?

Mauro Lucherini:

The IUCN Cat Specialist Group, based on the expected density of a cat the size of an Andean cat and the area potentially available in the Andes, estimated that less than 10,000 individuals are left. The truth is that in spite of many years of work in the four range countries, nobody has the answer to this question!! It must be clear that when you deal with an elusive, small-sized carnivores this basic question turns out to be also the most difficult to answer. In the case of the Andean cat, the obstacles are made greater by the fact that they mainly live in remote areas where altitude makes working (even moving, in some cases) very difficult!

Andean Cat |

However, my team in Argentina has been conducting the first study on population abundance of the High Andes carnivores through intensive camera trapping. This has a very demanding task that has been close to the limits our team capacities, but we were able to get estimates and conclude that in ideal habitats, density can be higher than expected, but also that high-density areas are probably small patches immersed in wide extensions that have almost with no Andean cats at all.

Mongabay: Why are Andean Cats endangered?

Mauro Lucherini: We cannot discard the possibility that Andean cats have always been rare, but it is probable that the extinction of wild populations of chinchillas (likely the main Andean cat prey) for fur trade has contributed in the past to reduce the Andean cat population numbers. What we do know is that human-induced habitat alterations are acting on top of this “natural” rarity and that the loss of few individuals from an area may drive the species to local extinction.

Constanza Napolitano, Lilian Villalba and Eliseo Delgado with Sombrita, the first Andean cat ever captured. Courtesy of Jim Sanderson. |

Present-day threats identified by AGA vary among countries and also regionally. While in the most productive and most populated areas of northern Bolivia and Peru extensive habitat modification caused by cattle grazing and collection of wood for fuel are thought to be affecting the availability of prey, in central Argentina mining is destroying large extensions of habitat. Throughout most of the range, hunting by man is certainly an important threat, whether it is related to the use of cat skins in traditional ceremonies or to the simple facts that all carnivores are perceived as pests by local people.

Mongabay: How many times have you seen an Andean cat?

Mauro Lucherini: Only once in 10 years of field work and, nevertheless, this entitles me to become part of the very exclusive club of the field biologists who has ever seen an Andean cat. A privilege that I feel I have to pay back, helping this cat to survive. And let me tell you that it was one of those moments that left a mark… I felt I was in the presence of the true Soul of the Andes!

Mongabay: Since it is so difficult to spot them, what keeps you motivated?

The Altiplano |

Mauro Lucherini: I think that there are some rational reasons and some deeper, more difficult to explain, motivations. I am convinced that, although Andean cats have certainly not the charisma of tigers, cheetahs or elephants, they can be used as flagships for the conservation of the whole High Andes ecoregion, a biome which is still little known and still possesses large wilderness areas, but which is in need for conservation because of its fragility and its high rate of endemism (meaning that a great proportion of the species living in the region cannot be found anywhere else). These are the reasons I find as a conservationist and a scientist. But I think that more important than that is the amazement I feel when I walk through the immense landscapes of the Altiplano, or when, in the absolute silence of a quiet morning, I hear a strange sound, I look around and see the huge wings of a condor drawing a sharp shadow on the desert mountain slopes. My true motivation comes from the connection that I was offered to establish with these landscapes.

Mongabay: Given that Andean cats are so rare, how do you track them?

Mauro Lucherini: In fact, rarity is only one of the difficulties that you have to face if you want to track these cats. In Argentina the Altiplano is huge and, in some cases, to reach the mountain ranges that are inhabited by cats you need a two-day 4×4 drive. Then you need to find a place where drinkable water is enough to set up a campsite. Finally, one needs to be fit enough to withstand the strong solar radiation after a freezing night, the constant winds that may easily turn into storms, and, especially, the lack of oxygen, which usually causes headaches and nausea for the first days. The techniques that we use range from the most ancient ones, such as searching for signs of presence of the cats to the most recent methods of camera trapping and DNA-based identification of scats.

Mongabay: Do Andean cats venture into the snow?

Mauro Lucherini: In Argentina they live in a region where it can snow in any season of the year and thus, obviously, Andean cats must be able to move in the snow, something that is also suggested by its ample paws. However, this is a very dry area and precipitations are rare. Thus, no photos of an Andean cat in the snow exist. Furthermore, they do not use the areas of permanent snow of the Andes, because they are too high and almost nothing lives there.

Mongabay: What is the best way to protect Andean cats and their prey?

Andean Cat |

Mauro Lucherini: We are convinced that in such a region, conservation must be placed in the hands of local people. Thus our strategy is mainly based on community awareness raising and participation. We aim to make locals feel proud of sharing their land with such a mysterious and beautiful cat and let them understand that the damage cats make to their domestic stock is likely minimal since the cat is too small to kill a sheep or a lama. Even chicken-killing is rare. In addition, since Andean cats are protected, we also remind people that killing them is against the law. Finally we advocate for the creation of more protected areas in the high Andes and for the development of conservation and management plans that includes the information we produce on the ecological needs of this species.

Mongabay: What do local people think of your efforts to preserve the cat?

Mauro Lucherini: Although most inhabitants of the South American Altiplano share common cultural roots, they occupy a 4000 km long stretch of mountain where villages are frequently quite isolated. So it is difficult to talk about the perceptions of local people as a whole. Initially they tend to be surprised to find out that this cat can be considered an international priority, but they are always quite happy when someone shows interest in their lives and traditional knowledge. And they are usually quite aware of how delicate is the balance of the ecosystems where they live and this makes them sensitive to alternative ideas or alternative sources of income.

Mongabay: How can people in places like the U.S. help Andean cat conservation?

Often overlooked, small wild cats are important and in trouble: An interview with small cat specialist Dr. Jim Sanderson Dr Jim Sanderson, a scientist with the Small Cat Conservation Alliance and Conservation International, is working to save some of the world’s rarest cats, including the Andean cat and Guigna of South America and the bay, flat-headed, and marbled cats of Southeast Asia. |

Mauro Lucherini: Americans are increasingly conservation-friendly and I think that when U.S. citizens decide to support a conservation project, the chances of success for that project increase dramatically. There are many forms of supporting a conservation project in a developing country. Funding is obviously fundamental, and I want to stress here that the total budget of AGA, with conservation actions taking place in 4 countries, is less than $100,000 per year. The development of a foreign tourism in the High Andes that is respectful of local people traditions and natural habitats could also dramatically change the situation we are dealing with. But even if US citizens only decide that Andean cats and their habitat must be saved, I think that we would soon be in a better position to help this wish come true. Public pressure on corporations can do what would appear miracles to our eyes now.

Mongabay: Do you have any tips for aspiring field conservationists?

Mauro Lucherini: Don’t think of field conservation as a job. If you think that you can live nicely by being a field conservationist, forget it. The true measure of success in conservation field work is that you love being out there. Scientific curiosity may help and it will help if you enjoy sharing hard work with friends, but you need to be self-motivated and aware that the fruits of the seeds you plant are more likely to be tasted by your children than by yourself.

Related

Group takes “venture capital” approach to conservation

|

(09/16/2008) An innovative group is using a venture capital model to save some of the world’s most endangered species, while at the same time working to ensure that local communities benefit from conservation efforts. The Wildlife Conservation Network (WCN), an organization based in Los Altos, California, works to protect threatened species by focusing on what it terms “conservation entrepreneurs” — people who are passionate about saving wildlife and have creative ideas for dong so. After a rigorous review process to identify and select projects that will have the greatest impact on conservation in developing countries, WCN provides the conservationist with fund-raising and back-office support, technology, and access to its network of people and resources.