Fish farms are killing wild salmon in British Columbia

Fish farms are killing wild salmon in British Columbia

mongabay.com

December 13, 2007

Parasitic sea lice infestations caused by salmon farms are driving nearby populations of wild salmon toward extinction, reports a study published in the December 14 issue of the journal Science.

The research raises concerns about the sustainability of salmon farming.

Authors Martin Krkosek and colleagues project a 99% collapse in pink salmon populations in four to ten years, or two to four salmon generations, if the sea lice infestations continue.

“The impact is so severe that the viability of the wild salmon populations is threatened,” said lead author Martin Krkosek, a fisheries ecologist from the University of Alberta. Krkosek and his co-authors calculate that sea lice have killed more than 80% of the annual pink salmon returns to British Columbia’s Broughton Archipelago. “If nothing changes, we are going to lose these fish.”

Young pink salmon with sea lice infection. Image courtesy of Alexandra Morton |

According to the researchers, the study raises questions about net pen aquaculture for salmon and other species.

“This paper is really about a lot more than salmon,” Ray Hilborn, a fisheries biologist from the University of Washington who was not involved in the study. “It is about the impacts of net pen aquaculture on wild fish. This is the first study where we can evaluate these interactions and it certainly raises serious concerns about proposed aquaculture for other species such as cod, halibut and sablefish.”

“Salmon farming breaks a natural law,” said co-author Alexandra Morton, director of the Salmon Coast Field Station. “In the natural system, the youngest salmon are not exposed to sea lice because the adult salmon that carry the parasite are offshore. But fish farms cause a deadly collision between the vulnerable young salmon and sea lice. They are not equipped to survive this, and they don’t.”

Grizzly bear with freshly-caught pink salmon. Image courtesy of Alexandra Morton |

“An important finding of this paper is that the impact of the sea lice is so large that it exceeds that of the commercial fishery that used to exist here,” says Jennifer Ford, a co-author and fisheries scientist. “Since the infestations began, the fishery has been closed and the salmon stocks have continued declining.”

“In the Broughton there are just too many farmed fish in the water. If there were only one salmon farm this problem probably wouldn’t exist,” Krkosek says.

“Over the years the number of farmed fish has increased,” said Morton. “There used to be only a few farms, each holding about 125,000 fish. But now we have over 20 farms, some holding 1.3 million fish. The farmed fish are providing a habitat for lice that wasn’t there before.”

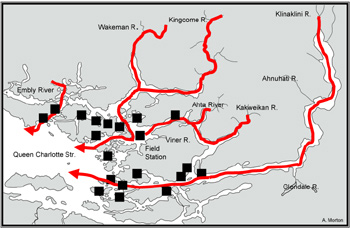

The researchers say it is not too late to take measures to slow the spread of sea lice to wild salmon, such as temporarily shutting down farms along the primary salmon migration route. “Even though they have complicated migration patterns they all have one thing in common — overall, the populations that are declining are the ones that are going past the farms,” said Mark Lewis, a mathematical ecologist at the University of Alberta. “There are two solutions that may work — closed containment, and moving farms away from rivers.”

Wild pink salmon routed in the Broughton archipelago (red), and salmon farms (black). Image courtesy of Alexandra Morton |

“If industry says it’s too expensive to move the fish farms or contain them, they are actually saying the natural system must continue to pay the price,” added Daniel Pauly, Director of the University of British Columbia’s Fisheries Center, who was not involved with the study. “They are, as economists would say, externalizing the costs of fish farming on the wild salmon and the public.”

“Wild salmon are enormously important to the ecosystem, economies, and culture. Now it is clear they are disappearing in place of an industry. People need to know this and make a decision what they want: industry-produced salmon or wild salmon,” concluded Morton.

This article is based on a news release from the University of Alberta.

M. Krkosek et al (2007). “Declining Wild Salmon Populations in Relation to Parasites from Farm Salmon,” Science 14 Dec 2007.