Two palm oil plantations have recently been established in Peru, supplanting primary forest. Satellite imagery analysis shows extent of the massive development, which is led by a group of companies tied to plantation entrepreneur and United Cacao CEO Dennis Melka. Photo courtesy of the Environmental Investigation Agency.

Two palm oil plantations have recently been established in Peru, supplanting primary forest. Satellite imagery analysis shows extent of the massive development, which is led by a group of companies tied to plantation entrepreneur and United Cacao CEO Dennis Melka. Photo courtesy of the Environmental Investigation Agency.

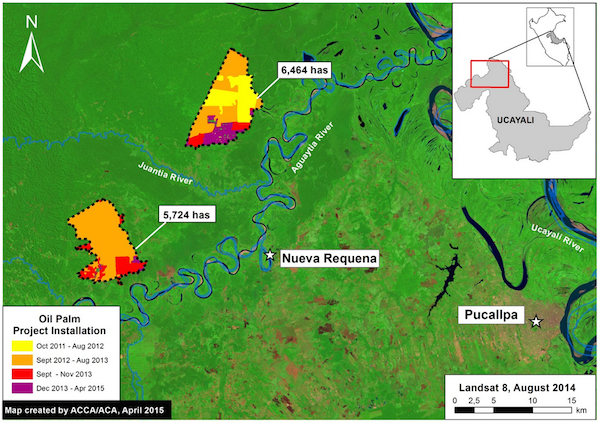

More than 9,400 hectares of closed-canopy Amazonian rainforest has been removed for two oil palm plantations in the Peruvian region of Ucayali since 2011, according to scientists working for MAAP, the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project. The two plantations are linked to Czech entrepreneur Dennis Melka.

Melka is the CEO of United Cacao, a Cayman Islands-based company that has been accused by scientists and NGOs of clearing more than 2,000 hectares of primary forest for a cacao plantation in another part of Peru while claiming to espouse a “sustainable” approach. He is also the founder, director, chairman, and CEO of United Oils, headquartered in the Cayman Islands according to some associates, and is a Singapore-based “palm oil refiner” according to others. Based on the public statements of at least one American investor, it appears that United Oils has also claimed that its operations are also sustainable.

Based on an analysis of satellite images going back to 1990, a total of 12,188 total hectares of standing forest had been leveled through the end of April, MAAP reported on April 27. MAAP is an initiative by a group of scientific and conservation organizations to accessibly present technical information about threats to the Amazon.

Seventy-seven percent of the total deforested area had not been cleared – in other words, it had been primary forest – for at least the last 25 years. Nearly another 20 percent, or around 2,300 hectares, was secondary forest that had been cleared at one time but had since grown back, the analysis showed.

Two large-scale oil palm projects near Nueva Requena in the central Peruvian Amazon began in late 2011 and now cover nearly 12,200 hectares, according to analysis recently released by MAAP. Data indicate that prior to plantation development, much of this area was occupied by primary forest. Image courtesy of MAAP. Click to enlarge.

One of the palm oil plantations. Photo courtesy of the Environmental Investigation Agency.

Oil palm development in Peru has burgeoned since the government decided in 2003 that the production of biofuels, including palm oil, should be a strategic priority. But the country has also made deforestation commitments, including a deal worth up to $300 million with Germany and Norway if it can scale back zero its rate of net deforestation by 2021.

To halt deforestation, scientists and conservationists have advocated the use of “degraded” lands for agriculture rather than forests. Degraded lands are areas that have been cleared and the forest hasn’t grown back, said Matt Finer, an ecologist with the Amazon Conservation Association who worked on the analysis. By that definition, only four percent of the two plantations in question could have been classified as degraded when plantation development began three and a half years go.

“Peru could and should have a future with oil palm,” Finer added, “but it needs to be strategically sited on the abundance of already-deforested lands that exist throughout the region.”

Finer, along with colleagues from Asociación para la Conservación de la Cuenca Amazónica (ACCA) based in Peru, used Landsat satellite images of the area from 2010 to develop a timeline of the deforestation. Between August 2010 and July 2012, crews began clearing the land, Finer said. Workers began planting oil palm before September 2013.

The team also examined images going back as far as 1990, the earliest available for this area, from which they established a baseline. Using a series of images from the next 25 years up until 2015, they demonstrated that the area remained “dense closed canopy” – that is, primary – forest until development of the plantations began in 2011.

Who is responsible?

The two plantations lie near the town of Nueva Requena on the north bank of the Aguaytía River, a tributary of the Ucayali River, which flows north to form the headwaters of the Amazon. Based on mongabay.com’s reporting from Ucayali, several related companies appear to be responsible for the deforestation. Grupo Palmas del Peru, Plantaciones de Ucayali, and Plantaciones de Pucallpa all operate in the area, and each has ties to Dennis Melka.

Data from Global Forest Watch support MAAP’s findings, showing large areas of tree cover loss near Pucallpa between 2012 and 2014 (2013 is the last year for which data are available) Much of that loss occurred within intact forest landscapes (IFLs), which are regions of undisturbed — primary — forest large enough and far enough from human activity to retain their original levels of biodiversity. In all, the area comprising the two plantations lost approximately 1,500 hectares of IFL tree cover in 2012 and 3,100 hectares in 2013. Click to enlarge.

A document obtained from the Ministry of Agriculture demonstrates that Plantaciones de Ucayali operates the southernmost of the two plantations, known as “El Fundo Zanja Seca.” Dated December 9, 2014, the document ordered the cessation of all agricultural activities until Plantaciones de Ucayali could show justification for major land use change as required by Peruvian law.

Local resident and farmer Ivan Flores said that Plantaciones de Pucallpa is developing the northern plantation, which is adjacent to several hundred hectares of forested land that his family owns.

“But it’s the same owners as Plantaciones de Ucayali,” he said when mongabay.com met with him in Pucallpa. Flores said representatives of the company have offered to buy his family’s land, but they have decided not to sell.

Repeated requests for clarification and comment from mongabay.com to Melka’s representatives in London, Pucallpa, Iquitos (where the headquarters of United Cacao’s Peruvian subsidiary is based), and Lima have been refused or gone unanswered.

It’s clear that the companies have significant financial and operational ties to each other. The business address registered for Plantaciones de Pucallpa and Plantaciones de Ucayali is listed as the Ucayali River Hotel in Pucallpa, according to documents from Peru’s tax administration authority, known as SUNAT.

Melka, who, in addition to being a Czech citizen, held an American passport at the time these companies were registered, is listed as a representative of each company, according to research by the Environmental Investigation Agency, an environmental NGO, and published in their report, “Deforestation by Definition.”

Melka is also a director of United Oils, as is his fellow United Cacao executive director Anthony Kozuch. United Oils is also reportedly has an office in Pucallpa, according to an investor’s website. Documents provided to mongabay.com by the Environmental Investigation Agency and obtained from SUNARP, the arm of the national government in charge of registering businesses that operate in Peru, show that United Oils and Grupo Palmas del Peru provided financing to both Plantaciones de Ucayali and Plantaciones de Pucallpa.

Connections between United Cacao and Melka’s oil palm interests exist as well. According to the company’s admission document to the London Stock Exchange’s Alternative Investment Market, United Cacao has also provided loans to, as well as received loans from, Palmas del Peru, Plantaciones de Ucayali, and Plantaciones de Pucallpa.

A question of definitions

Enrique Vasquez Da Silva, the president of the regional chapter of Convención Nacional del Agro-Peruano, an advocacy organization for Peruvian farmers and agricultural associations known as Conveagro, confirmed Melka’s business interests in Ucayali. Vasquez Da Silva told mongabay.com that Melka’s companies had two plantations in the region, on which they intend to plant about 11,000 hectares of oil palm. According to satellite imagery analysis by Sidney Novoa, a scientist with ACCA, which is part of MAAP, about 9,000 hectares of oil palm had been planted on the two sites as of early May.

Aerial imagery of the Nueva Requena region shows heavy machinery at work at a plantation site. Photo courtesy of the Environmental Investigation Agency Click to enlarge.

Newly planted oil palm at one of the plantations. Photo by John Cannon.

Vasquez Da Silva is happy to see oil palm projects injecting cash into the region’s economy. “We’re grateful that private investment has arrived here,” he said. “If it wasn’t for private investment, we wouldn’t grow the way we’re growing now.” To his mind, the influx of agricultural financing is responsible for amenities such as supermarkets in the regional capital of Pucallpa, as well as better roads to connect markets and settlements throughout the region.

He agrees with Finer that degraded land should be the target for plantations and that primary forest should be left alone. But Vasquez Da Silva also has a different definition of what constitutes primary forest. He said that primary forest “…is a forest that humans have never worked,” he said. “The hand of man has never touched it.” High levels of biodiversity, intact resources and valuable hardwood tree species such as mahogany are the hallmarks of primary forests, he added.

Given the intensity of impact humans have had on the Peruvian Amazon, Finer said such a strict definition isn’t practical and ignores the importance that dense forests have, including ones that humans have used.

“The ‘never been touched by the hand of man’ definition is extremely radical and makes no sense in an Amazonian context with indigenous communities living in even the most remote corners,” Finer told mongabay.com in an email.

“Selective, illegal logging of high-value tree species…remains rampant in Peru, thus very few places would be considered primary forest under that definition, including most protected areas,” he said. It’s not possible to define the oil palm developments in Ucayali as sustainable when they’ve come at the expense of so much primary forest, he added.

Plantation de Pucallpa dock in Nueva Requena. Photo by John Cannon.

Yet, Anholt Services, an American investment firm based in Connecticut and an investor in United Oils since 2012, touted the environmental leadership of United Oils in a September 2014 press release announcing the firm’s role in designing “a creative and mutually beneficial structure to enable [United Oils] to continue its development and expansion.”

Anholt managing director Ihab Massoud said in the release that Anholt was “excited” to help United Oils build out its operations because of “the company’s strong commitment to sustainable operations that create positive outcomes for the local community through outreach and assistance programs.” Rudolph Krediet, a partner at the investment firm, implied that the arrangement with United Oils would help Anholt ensure its land holdings achieve “their most sustainable and highest value uses over time.”

Representatives from Anholt did not respond to several requests for comment.

“Here in 2015 clearing any remaining primary Amazon rainforest for large-scale agriculture is unacceptable,” Finer said.

But a recent report on deforestation and oil palm in Peru by the United States Agency for International Development said that until Peru bolsters its enforcement of forestry laws to ensure primary forest isn’t given over to large-scale agricultural developers, “It is unrealistic to expect that large corporate or smallholder actors focus their palm oil development on deforested or degraded lands.” Typically, there aren’t large swaths of degraded land available, making it costly to buy the land from many individual owners and find enough adjacent areas to make for a viable and efficient plantation, the report’s authors write.

They also said that getting oil palm growers to target degraded lands was “highly unlikely” without better direction from the Peruvian government.

Finer echoed that assertion: “Peru can grow its oil palm sector without destroying primary forest, but it will require much better planning than what currently exists.”

Citations:

Suggested citations for data as displayed on GFW:

Greenpeace, University of Maryland, World Resources Institute and Transparent World. 2014. Intact Forest Landscapes: update and reduction in extent from 2000-2013. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on [date]. www.globalforestwatch.org

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland, Google, USGS, and NASA. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on [date]. www.globalforestwatch.org.