The cryptic treehunter lives the in highly threatened Atlantic forest, but researchers hold out hope that more might be found.

The cryptic treehunter (Cichlocolaptes mazarbarnetti). Photoart by Rolf Grantsau.

In October 2002, a team of ornithologists at Murici in northeastern Brazil observed and recorded the call of a bird. At that time, the team believed they had chanced upon a rare bird previously described by other researchers as the Alagaos foliage-gleaner (Philydor novasei).

“But then the bird vocalized!” Dante Renato Corrêa Buzzetti, an independent ornithologist who was a part of the team, told mongabay.com.

The bird’s loud screeching call was very different from what had been described for the Alagaos foliage-gleaner. In fact, it appeared to be similar to the call of another species, the pale-browed treehunter (Cichlocolaptes leucophrus), found in southeastern Brazil, Buzzetti said.

Habitat of the mysterious screecher and Alagaos foliage-gleaner (Philydor novasei) at Frei Caneca Jaqueira. Photo by Dante Buzzetti

So did the Alagaos foliage-gleaner exist at all?

Turns out it did. In 2013, Buzzetti’s colleague, Juan Mazar Barnett, found a bird in the state of Pernambuco that looked and sounded like the description of Alagaos foliage-gleaner.

“So the bird found in Pernambuco was the ‘true’ P. novaesi, and the bird recorded in Murici was a new species,” Buzzetti said.

The new species had a jet-black crown and forehead, its body was cinnamon-brown colored, and its tail was orange-rufous. And its throat and sides of its neck were a pinkish-buff.

Since the new bird species is very difficult to spot, Buzzetti and Barnett christened it “cryptic treehunter” in English. They published their findings in Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia last year.

In Portuguese, the bird was aptly named “gritador-do-nordeste,” with gritador meaning “screamer,” for its loud screeching call. Recordings of its calls can be heard here.

Adult female Alagaos foliage-gleaner (Philydor novaesi), left, and the cryptic treehunter (Cichlocolaptes mazarbarnetti), right. Photo from Barnett and Buzzetti, 2014. |

Buzzetti also dedicated the scientific name of the new species, Cichlocolaptes mazarbarnetti, to his colleague and lead author, Juan Mazar Barnett, who passed away before their manuscript was completed. The dedication, Buzzetti wrote, comes “in recognition of [Barnett’s] important contributions to the conservation of the Atlantic Forest in northeastern Brazil and its declining avifauna.”

The cryptic treehunter differs from the Alagaos foliage-gleaner in a number of ways. It is much larger than the Alagaos foliage-gleaner, and has a darker and more uniform forehead and crown, and a larger, longer bill. The two birds also occur in different parts of the forest, and feed differently. But some of these differences are subtle, Buzzetti said.

“The biggest differences between the two species are in the vocal repertoire,” he added.

So far, both the cryptic treehunter, and the Alagaos foliage-gleaner have been spotted in primary forest fragments in the states of Alagoas and Pernambuco in northeastern Brazil. Together, the intact forest cover in these two places, which is suitable for the birds, covers about 3,000 hectares.

In these forest fragments, the researchers estimate that there might be fewer than 10 individual cryptic treehunters left. So this newly described bird could well be one of the rarest birds in the world.

Given the precarious state of the species, the authors propose that it should be categorized as Critically Endangered at a national and global level. “We consider the situation of its conservation to be critical in that it will require urgent action to avoid its global extinction,” they write in the paper.

The Alagaos foliage-gleaner, too, is listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN Red List. According to the authors, the bird species was first discovered in Frei Caneca in the state of Pernambuco, where it was seen frequently until 2011. Since then, however, there have been no subsequent reports, and its conservations status in the area is considered critical, they write.

Loss of critical habitat

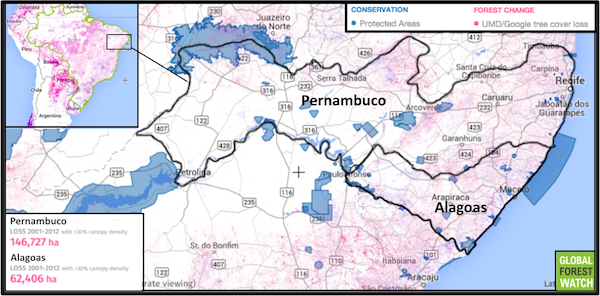

Forest cover in the two states where cryptic treehunters occur – Alagoas and Pernambuco – is rapidly declining. According to Global Forest Watch, between 2001 and 2012, Alagoas lost over 62,000 hectares of tree cover, and Pernambuco lost more than 146,000 hectares.

Map showing where tree cover loss has occurred in Alagoas and Pernambuco from 2001 through 2012. Click to enlarge.

Both Murici in Alagoas and Frei Caneca in Pernambuco, where the Cryptic Treehunters and Alagaos foliage-gleaners have been recorded, lie within a biodiversity hotspot called the Atlantic Forest. The region is a mosaic of diverse habitats, and is home to about 20,000 species of plants, more than 260 species of mammals, 700 species of birds, 200 species of reptiles, and about 280 species of amphibians. Most of these are endemic to the region, and found nowhere else in the world. Many more – like the cryptic treehunter – continue to be discovered and described.

The Atlantic Forest was once massive, spread across 150 million hectares. But unrelenting deforestation, mainly for sugarcane plantations and cattle ranching, quickly disintegrated the forest cover to less than 8 percent of its original area.

Moreover, these forests, which were once continuous, have been diced into 245,000 isolated fragments with little original forest cover, according to a study published in Biological Conservation. Most of these fragments, over 83 percent of them, are tiny – less than 50 hectares in area. Unsurprisingly, the status of many species in the Atlantic Forest today is critical. For instance, over 70 percent of the 199 endemic bird species found here are threatened or endangered, according to the study.

The cryptic treehunter occurs within the Pernambuco Centre of Endemism in the Atlantic Forest, located north of the river São Francisco. This centre includes the coastal forests of the states of Alagoas, Pernambuco, Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte, and is one of the most important centers of biodiversity and endemism in South America.

It harbors some of the most threatened birds of the country, such as the recently discovered Pernambuco pygmy owl. But it is also one of the most severely impacted areas, with only 2 percent of its original forests remaining, and is one of the least-known parts of South America to the scientific world.

%20in%20the%20canopy_%20Photo%20by%20Dante%20Buzzetti.jpg)

Detail of primary forest at Frei Caneca, showing the profusion of epiphytes (and in particular bromeliads) in the canopy. Photo by Dante Buzzetti.

The region of Murici is one of the most important areas of the Pernambuco Centre. Lying within Murici is the Murici Ecological Station (MES), a protected area, created in May 2001.

But the protected area status might not be enough to thwart habitat loss for the rare birds, the authors note. According to them, the bird is rapidly losing its habitat to deforestation.

Will the cryptic treehunter survive?

Every September and October of 2002 to 2007, the researchers detected “troubling levels of small to medium-scale deforestation.” They write that the “most unsettling then was the felling of much of the forest on the entire slope opposite the ravine that holds all recent records of C. mazarbarnetti, with evidence of further logging occurring between visits during the above period.”

In fact, according to the authors, the area being logged appeared to be ideal habitat for the cryptic treehunter.

The researchers stress the need to continue searching for the bird. But their hopes of finding it are low.

“Sadly our expectations for the long-term survival of this species are not high, and we may now be witnessing its passage through the temporal window representing the time-lag between deforestation and extinction,” they write.

From left to right male and female Philydor novaesi, female Cichlocolaptes mazarbarnetti at the center , and two male Philydor novaesi at right, showing the differences in contrast between tail and rump color. Photos from Barnett and Buzzetti, 2014.

“Conservation efforts at Murici have been undermined by political and bureaucratic problems since the ornithological discovery of the area. Without the political will to design and implement environmental policies and the commitment of private interests and stakeholders in Murici, little will be achieved for the conservation of its damaged forests.”

Although there are no recent records of both the birds in the region, it might be premature to declare them extinct, Buzzetti said.

It is necessary to conduct focused searches, Buzzetti added, especially by using information about the specific habitat of these birds, and their vocalizations.

“It is virtually impossible to locate C. mazarbarnetti inside bromeliad clumps in the forest canopy 20 meters high if it is not vocalizing!,” he said.

“In my opinion there is still some hope of finding the species in Murici, if the forest where the bird lives has not been removed, especially in remote areas with difficult access…but it is also necessary to know if there are still primary forests in the mountains at all.”

The authors also note in their paper that with increased interest of birders in Murici, ecotourism could provide a way out to protect the area.

“Murici and Frei Caneca are of maximum priority for the conservation of birds in the Atlantic Forest, and continent-wide, and the presence of this new species is a renewed reason to take actions for their preservation,” they add.

Citations:

Barnett, J. M., & Buzzetti, D. R. C. (2014). A new species of Cichlocolaptes Reichenbach 1853 (Furnariidae), the ‘gritador-do-nordeste’, an undescribed trace of the fading bird life of northeastern Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia-Brazilian Journal of Ornithology, 22(2), 20.

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland, Google, USGS, and NASA. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on [date]. www.globalforestwatch.org.

UNEP-WCMC, UNEP, and IUCN. “World Database on Protected Areas.” Accessed on [date]. www.protectedplanet.net.

Related articles

|

Endangered forests shrink as demand for soy rises

(03/10/2015) As battles over labeling genetically modified foods or displaying calorific breakdowns per serving rage on, it appears that a possibly more significant battle is in its infancy – where do all the ingredients on the package actually come from? |

|

Scientists reintroduce agoutis in rainforest in city of 12 million

(12/17/2014) When one thinks of Rio de Janeiro, one usually doesn’t think: rainforest. However, in the heart of the city sits a massive rainforest sprung over long-gone sugar and coffee plantations. The forest—protected today as the Tijuca National Park—is home to hundreds of threatened species, but no agoutis, a common ground mammal in Latin America. |

|

New endangered bird species discovered in Brazil

(12/04/2014) The Bahian mouse-colored tapaculo (Scytalopus gonzagai) has only just been discovered by scientists in the heavily logged Atlantic Forest of southeast Brazil — and it’s already believed to be endangered. |

|

Forest fragmentation’s carbon bomb: 736 million tonnes C02 annually

(10/09/2014) Scientists have long known that forest fragments are not the same ecologically as intact forest landscapes. When forests are slashed into fragments, winds dry out the edges leading to dying trees and rising temperatures. Biodiversity often drops, while local extinctions rise and big animals vanish. Now, a new study finds another worrisome impact of forest fragmentation: carbon emissions. |

|

Saving the Atlantic Forest would cost less than ‘Titanic’

(08/28/2014) Want to save the world’s most imperiled biodiversity hotspot? You just need a down payment of $198 million. While that may sound like a lot, it’s actually less than it cost to make the film, Titanic. A new study published today in Science finds that paying private landowners to protect the Atlantic Forest would cost Brazil just 6.5 percent of what it currently spends ever year on agricultural subsidies. |

|

Only 15 percent of world’s biodiversity hotspots left intact

(07/14/2014) The world’s 35 biodiversity hotspots—which harbor 75 percent of the planet’s endangered land vertebrates—are in more trouble than expected, according to a sobering new analysis of remaining primary vegetation. In all less than 15 percent of natural intact vegetation is left in the these hotspots, which include well-known jewels such as Madagascar, the tropical Andes, and Sundaland. |