Community-maintained forest in Delang District, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Photo by Revelation Chandra.

“We are treated like criminals caught stealing our own land,” M. Basri told Mongabay-Indonesia. The acting village head of Tompo Bulu in Sinjai Regency of South Sulawesi was referring to a letter by the regency’s government that effectively banned anyone from entering or harvesting food from government-owned forests. The declaration had already led to multiple arrests of farmers tending gardens their families had been managing for as long as anybody can remember.

The residents of the Karampuang region were understandably both upset and frightened. Upset at the violation of what they believe is their right to customary use of the land, and frightened that they would no longer have a means to feed themselves.

Residents of Karampuang still adhere to traditional customs, such as rice-pounding, or “appadekko.” Photo by Revelation Chandra.

Around 3,000 people from 833 households live in Tompo Bulu’s seven sub-villages. Traditional culture and ritual run thick in this area. The residents of Karampuang believe the area is where the cultures from eastern and western Indonesia first met. Local myth holds that the first leader of the area descended from the sky with a mandate that the locals must maintain their traditional way of life.

Long before the Indonesian government even existed, the people of Karampuang have carefully been managing the land to benefit the long-term needs of the community. They have established strict guidelines for when and where timber may be harvested, requiring that traditional rituals be performed before any tree is removed. If a community member is granted permission to cut, they are required to replant ten times the amount taken.

Some areas of the community forest are owned collectively, tended on behalf of less-fortunate community members who may have fallen on hard times, or for leaders who are busy with other responsibilities. Other areas are considered sacred, and nobody is allowed to hunt, harvest or cut anything from them. Anyone caught violating the rules faces harsh penalties, is evicted from the forest, and may be stripped of their standing in the community.

However, none of this was considered by the local government when it declared the land to be property of the state.

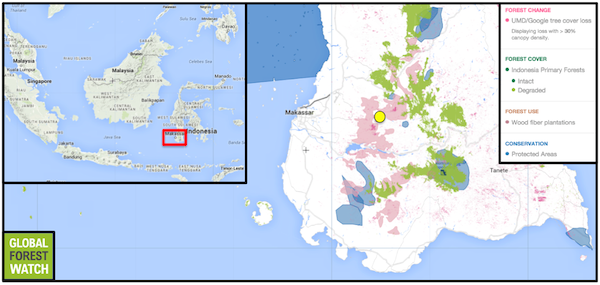

Sulawesi is home to a plethora of unique wildlife, the result of millions of years of separation by the Java Sea. Scientists frequently discover new species within the island’s lush forests – such as a carnivorous water rat. However, while the island has escaped the heavy plantation development of its neighbors like Kalimantan and Sumatra, forests are still being affected by human encroachment. According to Global Forest Watch, West Sulawesi lost approximately 13 percent of its tree cover from 2001 through 2012. South Sulawesi has been somewhat less affected, with about 5 percent of its tree cover lost during the same time (it should be noted that this loss likely does not entirely represent deforestation; some may be from the harvesting of established plantations). Still, South Sulawesi’s forests have been heavily degraded, with no remaining large tracts of intact primary forest. The Karampuang region (indicated by a yellow circle) is partially surrounded by a wood fiber concession. Click to enlarge.

The scramble to define who owns what is a response to ruling number 35 of the 2012 Constitutional Court, which formally recognized the existence of customary-use forests. Although this move was considered a success for indigenous rights, on the ground it resulted in confusion and conflict. In many cases, the burden of proof as to what constituted customary use forest was shifted to the under-resourced native population, who often had no formal documentation of their right to utilize the land.

Desperate to gain recognition of their rights, the residents of Karampuang area began mapping the land that maintains their culture and identity. With training from the national indigenous rights group, AMAN, they take GPS coordinates to mark the extent of their traditional-use land. They will then compile the information into a detailed map and submit it to the government.

“We must create this map so that it is clear where the boundaries of our customary use forest are. Although we already know where the forest is, it is important to create a clear description backed up with GPS waypoints,” said Gella Karampuang, a village elder.

He hopes this map will give his community leverage when dealing with the government, and help secure the right of his village to continue to maintain their ancestral lands.

Karampuang residents examine a map that is the basis for those they’ll create to define their land rights. Photo by Revelation Chandra.

Margono, B. Primary forest cover loss in Indonesia over 2000–2012. Nature Climate Change,doi:10.1038/nclimate2277. Retrieved June 30, 2014, from Nature

“Wood Fiber.” World Resources Institute. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on Jan. 07, 2015. www.globalforestwatch.org.