A tale of two fish: deep challenges ahead for Indonesia’s fishery managers

Part II – Boom but mostly bust: fighting over sardines in Indonesia’s Bali Strait

Part III – Over-depleted and undermanaged: can Indonesia turn around its fisheries?

Part IV – Seafood apartments and other experiments in fixing Indonesia’s fisheries

In spring and summer, after the monsoon storms have passed, the fishing boats set out again from tiny Kodingareng Island in the Spermonde Archipelago off the coast of South Sulawesi. In the afternoon heat, Abdul Wahid joins his fellow fishermen in the narrow shade of the beachfront village houses to check out the daily fish prices.

Three-kilo Spanish mackerel: $3.50. Triggerfish: $2. But the only price that really interests Wahid is for leopard coral grouper: $30/kg here in Sulawesi. The same fish will command $100/kg after it’s been rushed, alive, to Hong Kong by airplane or speedboat.

The trick for Wahid is to capture them alive from reef caves 30-plus feet under the sea. And he’s got to deliver them perfectly intact—no nicks or scratches. Only then will they be table-worthy in high-end East Asian restaurants, their ultimate destination.

Metal trap fishermen prep for a day out at sea, Spermonde Islands, South Sulawesi. Photo copyright (2014) Melati Kaye.

Wahid can manage this just using hook and line, making him something of a local celebrity. Leopard coral grouper (Plectropomus leopardus) fight back; they’re large, long-lived, and wily. In the hands of less skilled fishermen, metal traps or hooks would leave signs of struggle, reducing the value of the fish.

However, the grouper are too tempting a target to pass up, both for their premium price and the predictability of their mating and feeding grounds. So most fishermen resort to a quick and reliable—albeit illegal—shortcut: they temporarily stun the fish with cyanide poison and bring them in alive and intact.

Indonesia is the world’s largest supplier of live reef fish, shipping 2,414 tons of grouper (valued at $ 19,043,534) to Hong Kong in 2012, according to Fisheries Ministry statistics. Some industry experts estimate the actual amount of live fish exports to be orders of magnitude greater, including unrecorded or illegal shipments.

The live fish sell for $30 per kilogram. Dead fish fetch less than a third of that price. Careful hook and line fishermen can sometimes manage to keep their catch alive. But a surer method is to stun the fish with cyanide, an illegal but widespread practice. Photo copyright (2014) Melati Kaye.

The live fish sell for $30 per kilogram. Dead fish fetch less than a third of that price. Careful hook and line fishermen can sometimes manage to keep their catch alive. But a surer method is to stun the fish with cyanide, an illegal but widespread practice. Photo copyright (2014) Melati Kaye.

But this trade comes with unsustainably high costs. Targeting a population of apex predators like the grouper sets off a cascade of disruptions all the way down the ocean food web. With local species declining, fishermen are forced to upgrade their gear and range ever farther, often in the thrall of exploitative lenders.

Meanwhile, dousing reefs with poison destroys corals (of which Indonesia is the world’s leading repository of species diversity). The degraded coral also leaves islands stripped of their reef buffers and therefore prey to erosion and exposed to the full brunt of extreme storms.

The damage starts at the micro-level. Cyanide, a respiratory poison, disrupts the symbiotic relationship between corals and the zooxanthellae algae that grows in their skin. The corals protect the algae and provide the nutrient components for photosynthesis. In turn, the algae supply the oxygen and carbohydrate building blocks for the coral’s fats and calcium carbonate skeleton.

Suppressing photosynthesis, cyanide causes the algae to disassociate from its host coral, leaving the reef bleached. In a 1999 experiment, Sydney University researchers found that coral exposed for ten minutes to a cyanide solution less than half as strong as what these fishermen use die within 24 hours.

Cyanide bleaching proved to be the final coup de grace for Kodingareng’s reef. Just beyond the beachfront village, says Wahid’s neighbor, Faizal Wahab, there used to be an offshore forest of coral teeming with fish. But then dynamiters targeting schools of fish broke off chunks of the reef and cyaniders bleached much of the rest. Finally villagers, looking to shore up what was left of their beachfront, mined the dead coral to create breakwaters.

Now, when storms come through, there is nothing left offshore to buffer the waves, which rise up to ten feet high, slamming right into the houses, Wahid relates. During the monsoon “we had to sweep wave-borne sand off our second story balconies,” he laughs ruefully.

Leopard Coral Trout getting packed to be flown to Hong Kong from a warehouse in Makassar. Conversations with fishermen, buyers, warehouse owners revealed that a fish caught in Spermonde could arrive in Hong Kong in as little as two days. Photo copyright (2014) Melati Kaye. |

Such storm surges rapidly eat away the land, too. Wahid peers about 20 yards out to sea: “our beach used to extend all the way out to there.” Satellite analysis confirms that Kodingareng has lost 23 percent of its landmass since 2005, as recorded by local Universitas Hasanuddin Professor Dewi Badawing.

But if cyanide is hard on reefs, it’s hell on the groupers themselves. Napoleon Wrasse, high-finned grouper, and giant grouper—the most prized species—are all too easy for fishermen to locate, according to Hong Kong University biologist Yvonne Sadovy, because they live longer than other reef fish and have predictable feeding and spawning cycles.

“Large groupers prey on smaller groupers, who in turn control the numbers further down the line,” she adds. “So removing larger groupers has a knockdown effect within the food web.”

What’s more, by targeting the biggest of the big fish, cyaniders are messing up the groupers’ complicated sex life. Co-authoring the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s endangered listing for groupers and wrasses, Sadovy says these fish are euphoniously called “protogynous hermaphrodites.” That means they change gender part way through their life cycle. They spend their first two years spawning as a female and then switch to being males. So targeting the larger fish within a population skews the sex ratio, hastening depletion.

As Spermonde’s grouper populations implode, fishermen need to range farther afield. They sign up for three-to-four-month-long fishing expeditions that can carry them to the edges of Eastern Indonesia, greatly expanding their ambit of environmental damage. Because such a venture is beyond the means of most local captains, they seek funding from remote “bosses” as far afield as Thailand or Hong Kong.

One cyanide-using fisherman (who withheld his name to spare himself a third prison term) related how he was recruited into the trade when fish brokers first came to his island in 2007. Like any modern company, they tested their new hire with a trial internship. After teaching him techniques, they returned three months later to check on the quality of the groupers he caught.

Leopard Coral Trout getting packed to be flown to Hong Kong from a warehouse in Makassar. Conversations with fishermen, buyers, warehouse owners revealed that a fish caught in Spermonde could arrive in Hong Kong in as little as two days. Photo copyright (2014) Melati Kaye.

The cyanide fishery bosses ape modern corporations in another respect: undercapitalization. Irendra Radjawali, an Indonesian researcher at the Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Ecology in Bremen, Germany, has made a study of the patronage networks in the grouper trade. One “big boss” told Radjawali that he deliberately gives fishermen “limited money and petrol so that they can’t get home to Spermonde easily; they don’t have any choice other than to keep on fishing.”

Not that they’d have much choice anyway, thanks to climate change. The fishermen might as well go on months-long cruises, as there’s no point in staying home between November and March. Storms are expected to become more violent and the storm season longer in the Spermondes as a result of rising ocean temperatures. Household interviews by the Leibniz Center found that villagers are stranded at home during storm season, unable even to make the one-hour boat ride to Makassar in Sulawesi for supplies.

This raises the question: is there any future at all for the Spermonde fishing community? With the fish depleted, storms worsening, and storm-buffering reefs destroyed, will fishermen eventually be forced to migrate off the islands?

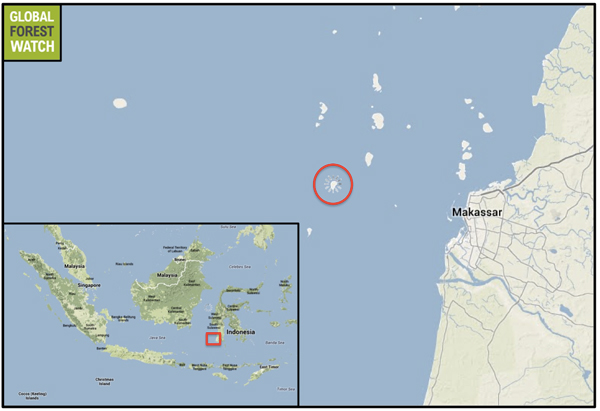

Kodingareng Island in Indonesia. Map courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

To prevent such a prospect, fisheries will need far better regulation. Government and local communities will have to enforce bans against bombing and cyaniding. While plenty of fishermen end up in jail for these crimes, they rarely make it to court. Instead, they get bailed out by their “bosses” and head right back to the reefs.

A better-monitored catch would shed more light on the value added at each stage of the live fish market, from reef to wok. This would provide fishermen and their governmental or NGO advocates with leverage to demand a fairer cut of the profits.

Better monitoring would also provide the basis for a more scientific fishery management regime. The same life-cycle predictability that makes the grouper so easy to catch could also be used to set up a system of no-take zones and seasonal restrictions to halt and eventually reverse depletion.

If that were to happen, though, the Spermonde fishing fleet would have to be reduced to a relative handful of highly skilled, artisanal Abdul Wahids. The rest of the grouper fishermen, including most of the cyaniders, would have to be redeployed to other trades.

But this process is already underway, with many younger fishermen switching of their own accord away from grouper fishing to hunt instead for sea cucumbers along the ocean border between Australia and Indonesia. Others are trying their hand at more sustainable aquaculture, sponsored by universities and corporate responsibility initiatives.

Related articles

Dying for Fiji’s Sea Cucumbers

(06/23/2014) Redfish, Greenfish, Blackfish. Pinkfish, Curryfish, Lollyfish. They sound like Dr. Seuss characters and certainly look like they should be. Yet these sausage-shaped, rubbery animals stippled in fleshy bumps are not fish at all, but an invertebrate in the group that includes sea stars, sea urchins and sand dollars. Sea cucumbers, referred to as ‘bêche-de-mer’ or ‘trepang’ when sold as dried food have a high value – an individual in Fiji can fetch about $80 US.

U.S. raises $800 million for oceans, including $7 million from Leonardo DiCaprio

(06/19/2014) A U.S. State Department conference on the oceans raised an impressive $800 million for marine conservation this week. The conference was also notable for the announcement by President Obama of an intent to significantly expand the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

Trawling: destructive fishing method is turning seafloors to ‘deserts’

(05/28/2014) Previous research has linked trawling to significant environmental impacts, such as the harvest of large numbers of non-target species, collectively termed “bycatch,” as well as destruction of shallow seabeds. Now, a new study finds this method is also resulting in long-term, far-reaching consequences in the deeper ocean and beyond.

Former Miss South Pacific steps into new conservation role

(05/15/2014) Alisi Rabukawaqa, an articulate, vibrant, 26-year-old Fijian known in Oceania as Miss South Pacific 2011, has set her sights on a novel conservation program in Fiji. The Conservation Officer program, created in 2013, supports natural resource management within villages in Fiji and links them with the government arm overseeing the needs of indigenous Fijians. Mongabay.org Special Reporting Initiative Fellow Amy West sits down for an interview.