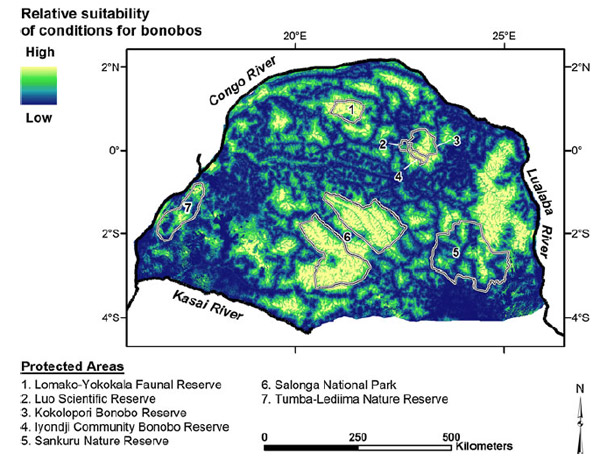

Only 27.5 percent of potential bonobo habitat is still suitable for the African great ape, according to the most comprehensive study of species’ range yet appearing in Biodiversity Conservation.

“Bonobos are only found in lowland rainforest south of the sweeping arch of the Congo River, west of the Lualaba River, and north of the Kasai River,” lead author Jena Hickey with Cornell told mongabay.com. “Our model identified 28 percent of that range as suitable for bonobos. This species of ape could use much more of its range if it weren’t for the habitat loss and forest fragmentation that gives poachers easier access to illegally hunt bonobos.”

The paper, involving over 30 scientists, analyzes the world’s bonobo population using nest counts, remote sensing imagery, and computer modeling. The researchers found that bonobo presence was mostly correlated with human absence.

“Distance from agriculture and forest edge density best predicted bonobo occurrence […] These results suggest that bonobos either avoid areas of higher human activity, fragmented forests, or both, and that humans reduce the effective habitat of bonobos,” the scientists write.

Not identified as a separate species from the more well-known chimpanzee until the Twentieth Century, bonobos (Pan paniscus) have been little studied compared to their more widespread cousins. Bonobos are only found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), separated from chimpanzees by the Congo River. Smaller than chimps, bonobos are most known for their matriarchal society and their tendency to solve conflict through sexual behavior, which has given them the moniker of the “make love, not war” apes.

“For bonobos to survive over the next 100 years or longer, it is extremely important that we understand the extent of their range, their distribution, and drivers of that distribution so that conservation actions can be targeted in the most effective way,” said co-author Ashley Vosper with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). “Bonobos are probably the least understood great ape in Africa, so this paper is pivotal in increasing our knowledge and understanding of this beautiful and charismatic animal.”

The bonobo was once known as the ‘pygmy chimpanzee.’ Photo by: Crispin Mahamba/Wildlife Conservation Society-DRC Program.

Compiling data from 2003-2010, the scientists identified 2,364 “nest blocks,” i.e. a one hectare area containing bonobo nests. Researchers have yet to estimate the total population of bonobos, but in the past they have speculated somewhere between 30,000 and 50,000.

The scientists believe that bonobos largely avoid human areas because of rampant bushmeat hunting.

“Areas closer to agriculture and roads are closer to human populations who tend to hunt in the surrounding forest,” they write. “Roads and navigable rivers provide human access to areas that would otherwise likely be less vulnerable to hunting.”

Although the research shows that bonobos have potentially lost a lot of territory as human populations have expanded and swelled in the DRC, it also points to new opportunities. Of the remaining bonobo range, only 27.5 percent was found in protected areas.

“The fact that only a quarter of the bonobo range that is currently suitable for bonobos is located within protected areas is a finding that decision-makers can use to improve management of existing protected areas, and expand the country’s parks and reserves in order to save vital habitat for this great ape,” noted co-author Innocent Liengola, WCS’s Project Director for the Bonobo Conservation Project.

One of the major challenges facing bonobos is the instability of the DRC, which after decades of civil war, currently faces armed rebels, rampant poaching, an HIV crisis, and one of the world’s highest poverty rates. Meanwhile, the population is steadily increasing at about 2.7 percent annually.

Predicted range of the bonobo. Map from Hickey et al.

Bonobo. Map from Hickey et al.

Citations:

- Hickey et al. (2013) Human proximity and habitat fragmentation are key

drivers of the rangewide bonobo distribution. Biodiversity Conservation. DOI 10.1007/s10531-013-0572-7Related articles

Remarkable new monkey discovered in remote Congo rainforest

(09/12/2012) In a massive, wildlife-rich, and largely unexplored rainforest of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), researchers have made an astounding discovery: a new monkey species, known to locals as the ‘lesula’. The new primate, which is described in a paper in the open access PLoS ONE journal, was first noticed by scientist and explorer, John Hart, in 2007. John, along with his wife Terese, run the TL2 project, so named for its aim to create a park within three river systems: the Tshuapa, Lomami and the Lualaba (i.e. TL2), a region home to bonobos, okapi, forest elephants, Congo peacock, as well as the newly-described lesula.

Innovative conservation: bandanas to promote new park in the Congo

(07/16/2012) American artist, Roger Peet—a member of the art cooperative, Justseeds, and known for his print images of vanishing species—is headed off to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to help survey a new protected area, Lomami National Park. With him, he’ll be bringing 400 bandanas sporting beautifully-crafted images of the park’s endangered fauna. Peet hopes the bandanas, which he’ll be handing out freely to locals, will not only create support and awareness for the fledgling park, but also help local people recognize threatened species.

Without data, fate of great apes unknown

(03/12/2012) Our closest nonhuman relatives, the great apes, are in mortal danger. Every one of the six great ape species is endangered, and without more effective conservation measures, they may be extinct in the wild within a human generation. The four African great ape species (bonobos, chimpanzees and two species of gorilla) inhabit a broad swath of land across the middle of Africa, and two species of orangutans live in rainforests on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra in Southeast Asia.

Unsung heroes: the life of a wildlife ranger in the Congo

(11/01/2011) The effort to save wildlife from destruction worldwide has many heroes. Some receive accolades for their work, but others live in obscurity, doing good—sometimes even dangerous—work everyday with little recognition. These are not scientists or big-name conservationists, but wildlife rangers, NGO staff members, and low level officials. One of these conservation heroes is Bunda Bokitsi, chief guard of the Etate Patrol Post for Salonga National Park in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In a nation known for a prolonged civil war, desperate poverty, and corruption—as well as an astounding natural heritage—Bunda Bokitsi works everyday to secure Salonga National Park from poachers, bushmeat hunters, and trappers.