Madagascar’s first people may not have driven the island’s largest animals to extinction, suggests new study.

New research indicates that Madagascar was occupied some 2,500 years earlier than previously established. The findings, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests a more complex view of the human role in the extinction of the island’s mega-fauna.

A large body of research holds that village communities began to appear in Madagascar around 500 AD. These were established by people of Indonesian and East African heritage, according to past studies that found linguistic similarities between the Malagasy languages of southeastern Borneo as well as genetic markers tying modern-day Malagasy people to both Indonesia and East Africa. But there have been plenty of hints that people came to the world’s third largest island well before 500 AD. For example, pollen and charcoal disposition have found evidence of fires and vegetation change linked to human activity around 0 AD, while cut-marks on prehistoric animal bones date to at least 400 BC, and possibly as far back as 2200 BC. But until now there were few artifacts that could be used to establish a presence of humans on Madagascar.

The new study looks at a site in northeastern Madagascar: specifically “a rock shelter” overlooking the Bay of Iharana near Vohémar. Researchers, led by the late Robert E. Dewar of Yale University, unearthed scores of flaked stone items made from materials brought from some distance away.

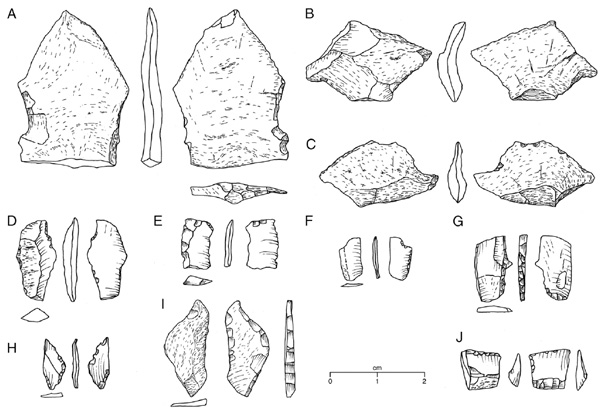

The chipped stone items from Lakaton’i Anja. Courtesy of the authors.

“Flaked stone items recovered primarily from washing and sorting are very small, a majority from a range of crypto-crystalline silicates, which we term ‘chert,’ and a minority of a volcanic glass which we term ‘obsidian’,” the authors write, noting that there are no known sources of obsidian in northern Madagascar. “Some of the fragments and flakes have pot-lid scars attributable to either deliberate heating, which improves flaking, or accidental burning.”

Using carbon dating, the researchers estimate the age of the stone tools — which are similar to ones found in Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia — at 3,500 to 4,400 years, corresponding to “roughly 1460-2370 BC.” The researchers say the results provide evidence of “intermittent occupation by small groups engaged in foraging” at the site.

Comparing egg size between a chicken, an ostrich, and an extinct elephant bird (Aepyornis maximus).

The findings also suggest the need for a more nuanced understanding of the extinction of large-bodied animals — like gorilla-sized lemurs, giant tortoises, hippos, and elephant birds — from Madagascar. Conventional wisdom holds that Madagascar’s largest wildlife was rapidly wiped out once man established a foothold on the island, hunting the meatiest animals and slashing and burning forests for rice and cattle grazing. The new study however shows that humans—albeit in small and perhaps staggered groups—may have been exploiting resources on Madagascar for a much longer period of time than traditionally thought.

“Many have viewed the Holocene extinctions as catastrophic and quick following human settlement of Madagascar, by analogy with well-known cases in Pacific islands. However, many now-extinct species in Madagascar have been dated after A.D. 1, and extinctions continued until at least A.D. 1500,” the authors write.

-

“Our unique evidence shows that extinctions occurred long after human arrival on the island. Although human activities were involved, including hunting, the specific causes and pattern remain to be determined. More generally, the view that Madagascar’s history can be sharply divided by the arrival of humans between an undisturbed Eden and anthropogenic chaos is no longer tenable. The activities of foraging populations have environmental consequences that differ in both degree and nature from those of Iron Age farmers and pastoralists, and changes in paleoenvironmental proxies interpreted as signaling ‘human arrival’ may in fact be signals of a change in human economy. Fire is used differently as a tool by foragers, farmers, and pastoralists. Interpreting Holocene histories of distinguishing not only between ‘natural’ and ‘anthropogenic,’ but also among different, historically distinct, patterns of fire use by people.”

The researchers conclude by urging more archeological research to locate and excavate more forager sites to understand “the chronology, origins, geographic spread, and environmental impacts of the human occupation of Madagascar.”

Note: Lead author Robert E. Dewar died in April 2013

CITATION: Robert E. Dewar et al (2013). Stone tools and foraging in northern Madagascar challenge Holocene extinction models. Published online before print July 15, 2013, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306100110 PNAS July 15, 2013

Related articles