An adult common midwife toad. Photo by: Gonçalo M. Rosa.

The chytrid fungus—responsible for millions of amphibian deaths worldwide—is now believed to be behind a sudden decline in the common midwife toad (Alytes obstetricans), according to a new paper in Animal Conservation. Researchers have detected the presence of the deadly fungus in the Serra da Estrela, north-central Portugal, home to a population of the midwife toad.

“Our findings point to an outbreak of [the disease] chytridiomycosis likely being responsible for the population decline and observed disappearance of this species,” lead author Gonçalo M. Rosa told mongabay.com.

Microscopic fungi, namely Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), which live in aquatic conditions, are responsible for the disease. The disease compromises the osmotic properties of amphibian skin, as well as an individual’s electrolyte blood levels, eventually leading to cardiac arrest.

The IUCN describes chytridiomycosis as “the worst infectious disease ever recorded among vertebrates in terms of the number of species impacted, and its propensity to drive them to extinction.” It has the potential to cause massive population declines in a matter of weeks while also disproportionately eliminating species that are rare, specialized and endemic.

Midwife toad tadpole. Photo by: Gonçalo M. Rosa. |

In 2009, scientists in north-eastern Portugal found a number of dead common midwife toads; tests soon uncovered the presence of Bd. The extent of the outbreak was still unknown. Only recent have studies revealed the full effects.

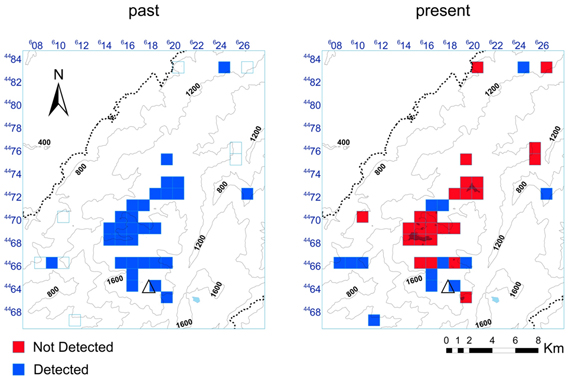

“This was one of the most abundant amphibian species at the park and shockingly our study shows that it has disappeared from almost 70% of the areas where it was recorded in the past,” explains Rosa, adding that “signs of breeding activity were limited to 16% of the confirmed breeding sites in the past, and larvae are now less abundant: in sites where we have records of thousands of tadpoles, we now find a dozen.”

Such losses set alarm bells ringing for biodiversity within the region. Like any substantial loss of any one species, the knock-on effects could be far reaching.

Rosa describes the common midwife toad as playing an “essential role in terms of the ecosystem, sitting right in the middle of the food chain.”

He then goes on to explain that “thousands of over-winter large and fat tadpoles in a pond represent a considerable part of biomass and act as a nutritional prey item for many species, from invertebrates to snakes and birds.”

Interestingly however, not all populations of common midwife toads are at risk. Many factors have been known to govern Bd’s effects including temperature, infection dose, age, life-stage, species and even altitude. Disease-resistant species such as the American bullfrog are a major concern as they act as carriers, potentially exposing new populations to it.

“In Serra da Estrela, while some populations seem to have disappeared following Bd outbreaks, others (particularly in lower altitude sites) persist without being (apparently) affected, despite high levels of infection,” explains Rosa.

Bd’s presence is nevertheless significant, since its infectious properties pose a potential life-threatening risk to other amphibians in the region.

Species occupying similar altitude levels include the common toad (Bufo bufo), the Natterjack (Epidalea calamita), and urodeles (salamanders and similar amphibians) like the fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra), the Bosca’s newt (Lissotriton boscai) and the marbled newt (Triturus marmoratus).

Since the diseases’ discovery in 1938, an effective treatment has not yet been formulated for wild amphibians and its future is still largely unknown.

“Several treatments have been tested (successfully) to clear Bd in infected frogs in controlled captive conditions,” says Rosa but “the applicability and success of such methods in natural populations is a totally different story.”

“Complete eradication of the disease from the environment has been shown to be virtually impossible,” he stresses.

Rosa goes on to highlight the importance of disease mitigation, insisting it is one of the key components in population management. He also states that major awareness of the problem in general populations is key to preventing the spread of diseases such as chytridiomycosis.

The IUCN currently recognizes 6000+ species of amphibians. Around 41% of these are believed to be threatened with extinction. While habitat loss remains the main protagonist behind depleting amphibian numbers, its combined effect with climate change and diseases such as chytridiomycosis could spell disaster for an essential group of organisms.

Individual common midwife toad found dead in a pond in Serra da Estrela Natural Park in Portugal. Photo by: Gonçalo M. Rosa.

Presence/absence data of post-tadpole stage common midwife toad at Serra da Estrela Natural Park. Past map summarize data prior to 2009, and present map show the result of surveys carried out during 2010/2011. Axes show 1 x 1 km UTM coordinates. Map by: Gonçalo M. Rosa.

Big pond is called ‘Lagoa dos Cântaros’ and it is one of the sites were massive decline have been recorded. Photo by: Madalena Madeira.

Common midwife toad still sporting a tail shortly after emerging from the tadpole stage. Photo by: Gonçalo M. Rosa.

CITATION: Rosa, G. M., Anza, I., Moreira, P. L., Conde, J., Martins, F., Fisher, M. C., Bosch, J. (2012), Evidence of chytrid-mediated population declines in common midwife toad in Serra da Estrela, Portugal. Animal Conservation. DOI: 10.11 11/j.1469-1795.2012.00602.

Related articles

Meet Cape Town’s volunteer ‘toad shepherds’

(11/08/2012) August marks the last month of winter in South Africa, and, as temperatures begin to rise, activists in Cape Town prepare for a truly unique conservation event. Every year at this time western leopard toads (Amietophrynus pantherinus) endemic to the region and Critically Endangered, embark on a night-time migration through Cape Town from their homes in the city’s gardens to the ponds they use as breeding sites—as far as three kilometers away. This season over one hundred volunteers took to the streets, flashlights in hand, to assist the toads in navigating the increasing number of man-made obstacles in their path. Among them was life-long resident and mother, Hanniki Pieterse, who serves as an organizer for volunteers in her area.

Artificial ‘misting system’ allows vanished toad to be released back into the wild

(11/01/2012) In 1996 scientists discovered a new species of dwarf toad: the Kihansi spray toad (Nectophrynoides asperginis). Although surviving on only two hectares near the Kihansi Gorge in Tanzania, the toads proved populous: around 17,000 individuals crowded the smallest known habitat of any vertebrate, living happily off the moist micro-habitat created by spray from adjacent waterfalls. Eight years later and the Kihansi spray toad was gone. Disease combined with the construction of a hydroelectric dam ended the toads’ limited, but fecund, reign.

Climate change may be worsening impacts of killer frog disease

(08/13/2012) Climate change, which is spawning more extreme temperatures variations worldwide, may be worsening the effects of a devastating fungal disease on the world’s amphibians, according to new research published in Nature Climate Change. Researchers found that frogs infected with the disease, known as chytridiomycosis, perished more rapidly when temperatures swung wildly. However scientists told the BBC that more research is needed before any definitive link between climate change and chytridiomycosis mortalities could be made.

3000 new species of amphibians discovered in 25 years

(07/31/2012) The number of amphibians described by scientists now exceeds 7,000, or roughly 3,000 more than were known just 25 years ago, report researchers in Berkeley.