The Department of Energy last week announced nearly $6 million in research grants for projects seeking to exploit methane hydrates as a new source of energy.

Gas hydrates are solid methane ice deposits typically found at the bottom of the ocean and in terrestrial permafrost. They are stable only under low temperature and relatively high pressure. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that some 200,000 trillion cubic feet methane hydrates lie within U.S. coastal waters — enough potential energy to fuel the country for centuries.

|

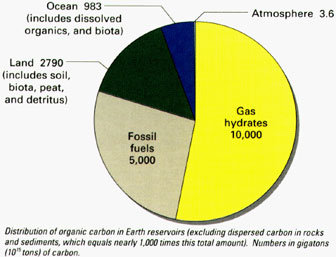

But frozen methane deposits raise environmental concerns. Methane is 21 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas and development of hydrates could trigger methane release into the atmosphere. Furthermore, the worldwide amount of carbon presently locked in gas hydrates is conservatively estimated to be twice the amount of carbon to be found in all the world’s known oil, gas, and coal deposits. Burning these deposits would therefore generate substantial greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to another potential worry: the stability of hydrates. Some scientists believe that destabilization of hydrate deposits may have played an important role in past episodes of rapid climate change by causing fluctuations in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases.

The rapid decomposition of frozen methane hydrate deposits may have been responsible for the sharp spike in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases during the Palaeocene/Eocene thermal maximum (PETM) — a period of rapid, extreme global warming about 55 million years ago. The methane released during melting would have reacted with oxygen to produce huge amounts of carbon dioxide, also a potent greenhouse gas. The warming caused a mass extinction among marine animals and helped usher in the “Age of Mammals.”

The new Department of Energy grants are geared toward evaluating methane hydrates’ potential as a future energy supply as well as their environmental performance, according to the agency.

Related articles