Belo Monte protest. Photo credit: Atossa Soltani/ Amazon Watch / Spectral Q.

The Brazilian government is putting its global environmental leadership at risk by ignoring scientific concern on large infrastructure projects and changes in the country’s forest laws, warned an association of more than 1,200 tropical scientists gathering last week in Bonito, Brazil on the heels of the disappointing Rio+20 Earth Summit.

While world leaders convened in Rio de Janeiro for the U.N. Conference on Sustainable Development scientists from 48 countries met at the 49th annual meeting of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC).

At the conclusion of the meeting, ATBC issued a declaration [PDF] urging the Brazil government maintain its leadership position on environmental conservation and sustainable development, by continuing to utilize scientific input and invest in science and education.

“Brazil’s success in advancing science and conservation, while achieving impressive economic growth and significant improvements in human welfare are being watched by the world as a potential model for environmentally sustainable development,” said John Kress, a botanist at the Smithsonian Institution who serves as ATBC Executive Director, in a statement. “But recent developments raise concerns.”

These concerns include infrastructure projects like the controversial Belo Monte dam; changes in the Forest Code, which stipulates how much forest a landowner must preserve on their property; and a proposal to change how protected areas and indigenous lands are allocated.

“Brazil was on a good track on environmental issues over past 10-20 years,” said Carlos Fonseca, a botanist at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte. “We saw real changes in how society perceives and values the environment. Recently this changed drastically mostly due to Congress, which is changing the laws to go against popular opinion and the advice of scientists. This is threatening a lot of the achievements we’ve had in the past two decades.”

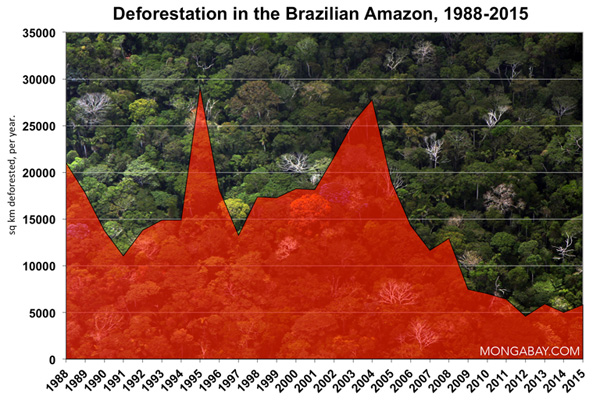

The declaration highlighted two lesser-known issues — indigenous land allocation and the Tapajós River dam — to illustrate threats to Brazil’s environmental image, which has been bolstered in recent years by a nearly 80 percent drop in the deforestation rate in the Amazon during a time of strong economic growth. In the past economic growth was often associated with a rise in deforestation.

The proposed change in how indigenous lands and protected areas are designated would give more power to Brazilian Congress, which recently passed the weakened Forest Code, and industrial development agencies in determining what lands are set aside as indigenous territories and parks.

“We are concerned about a push in Congress to start reviewing the tenure of the indigenous lands, which is something that is unique to Brazil,” said José Manuel Fragoso, an ecologist at Stanford University. “Indigenous peoples depend on these lands for their livelihoods and are also very important partners for biodiversity conservation.”

“We feel that Brazil has been in a leadership position with regard to the environment so we’re disappointed to see the government failing to address concerns raised by the scientific community on some of these large-scale industrial development projects like the Belo Monte dam and the proposed project on the Tapajós River,” said Fragoso.

The scientists also noted the apparent neglect of ecosystems outside the Amazon rainforest, including the Mata Atlantic forest, cerrado, caatinga, pantanal, and pampas grasslands.

“But other important ecosystems… have not received the same level of attention,” said Kirsten Silvius of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. “Indeed, the cerrado is being converted at a more than twice the rate of the Amazon and is at extreme risk from synergistic interactions between fragmentation, climate change and fire.”

The declaration called on the Brazilian government to “rigorously and transparently consider and utilize scientific information” in decision-making processes to ensure projects and legislative changes don’t undermine Brazil’s progress on “green growth.”

“Brazil has the once in a lifetime opportunity to lead the world on the environment. It has a wealth of scientific capacity and resources available to develop evidence-based policy,” said Toby Gardner. “It shouldn’t pass up this opportunity.”

Related articles