Long seen as a pariah for its high rate of deforestation, the world is starting to look to the Brazilian state of Pará for ideas to protect rainforests.

Brazil can reduce Amazon deforestation to zero by 2020 while boosting rural livelihoods and maintaining healthy economic growth, the governor of Pará told mongabay.com on the sidelines of the Skoll World Forum, a major conference on social entrepreneurship, last week.

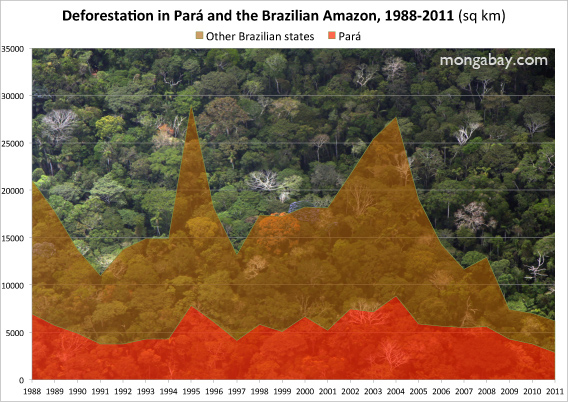

Governor Simao Jatene is hopeful that a revolution in land management and governance can turn the tide in Pará, a state that is three times the size of California and has lost more Amazon forest — 90,000 sq km of Amazon forest since 1996 — over the past decade-and-a-half than any other in Brazil.

The governor is no treehugger. His motivation comes from a wide-ranging constituency that demands an end to deforestation.

“There is no longer any question that we need to stop deforestation,” he said. “The big question is how.”

The state of Para, in red

According to the governor, the recipe for success involves shifting from top-down approaches to bottom-up innovations based on multi-stakeholder participation.

“The historical approach was top-down, but top-down has very limited chance for success in Pará, which is 1.25 million square kilometers and has everything from intensive agriculture to the forest frontier to remote areas of pristine forest.”

Jatene believes command-and-control efforts have contributed significantly to the 78 percent drop in deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon in recent years, but going further means turning more control over to municipalities, which can adopt policies specific to local conditions within the framework of broader government deforestation-reduction targets.

Jatene sees Pará’s CAR (Cadastro Ambiental Rural) as providing the structure under which local initiatives operate. The cadastro is a system that requires ranchers and farmers to register their holdings. Participation in CAR has grown exponentially since it launched in 2009, from 400 in its first year to 40,000 in 2011. The reason is simple: producers can’t get credit or sell to mainstream buyers if they aren’t registered.

Jatene says Pará aims to have 100,000 producers — about 50 percent of the total in the state — registered by 2013.

“A lot of deforestation happened in the Amazon because of a belief on the part of the perpetrators that they wouldn’t be punished,” Jatene said. “With CAR, land ownership is no longer anonymous.”

CAR is a first step for a landowner to get an environmental license. Under CAR, a landowner must have a long-term plan to restore any illegally cleared forestland to required levels.

Governor Simão Jatene at a rally. Courtesy of Jatene. |

“If a landowner does not come into compliance, they are punished. The point of CAR is to stop new deforestation.”

CAR is good for enforcement and incentives, which Jatene argues are needed to encourage good practices, especially among smallholders, who account for a growing proportion of deforestation as overall clearing declines.

“The challenge is getting smallholders in the cadastro,” he said. “We started with big ones that are 80 percent of the problem.”

“The carrot for smallholders is infrastructure — that brings them into CAR.”

Jatene asserts that infrastructure includes improved roads, rather than new roads, which decades of research have shown drive deforestation.

“Better roads improve livelihoods because product reaches market faster and in better condition,” he said.

Health and education are further carrots.

When the right mix of governance and incentives come together, the transformation can be surprising. Take the case of Parágominas, a municipality in Pará whose deforestation rate was so high it landed on a federal blacklist, restricting its access to credit and markets.

Parágominas turned itself into a “green city”, nearly eliminating illegal deforestation by adopting new forest management practices, establishing a local environmental police force, and offering training to ranchers and farmers to increase yields by better utilizing already deforested lands. It was removed from the blacklist last year, becoming a model for other jurisdictions as far away as the Congo and Indonesia.

A campaign poster for Governor Simão Robison Oliveira Jatene |

“Municipalities that are pushing the agenda are seeing the benefits already,” he said. “They are trying to replicate Parágominas model.”

But the period of transition from a deforestation-driven model to low carbon development can be painful initially.

“The initial transition triggers job loss because the local economy is deforestation-based,” Jatene said. “Bridging that transition is the critical moment for government.”

“That’s why a green education program is important.”

Jatene sees the need for substantial investments in education at the municipality level to shift livelihoods away from activities that destroy forests.

“Universal access to education is almost there in Pará,” Jatene explained. “The question is quality of the education.”

“Low skill jobs tend to be in deforestation industries. That’s why they need education.”

New industries and innovation require education and training. Jatene says that Pará could triple its agricultural output by making more productive use of poorly utilized and already deforested land. Technology could boost yields even further. But Jatene also sees potential beyond agriculture.

“We need a knowledge revolution,” he said. “[We] can generate ground-up knowledge in terms of forest use, including non-wood forest products like açaí and medicinal plants.”

Governor Jatene says the mechanism for REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) isn’t clear yet for governors, noting that it excludes protected areas. This ends up being a disincentive for setting up new conservation areas. The governor is active in the Governors’ Climate and Forests Task Force (GCF), an initiative pushing for state-to-state REDD pilot projects and agreements. |

The Amazon has great wealth in the form of its biodiversity, which could become the basis of new indigenous industries.

The governor also sees the potential for capitalizing on the value of ecosystem services, like carbon and water.

“The sharp reduction in deforestation in Brazil the last few years was as big a contribution as the Kyoto Protocol,” he said. “This was done without international payments for environmental services — Brazil wasn’t paid. This could be a very powerful tool for further reduction.”

But locals will need to see direct benefits from reducing deforestation to make such programs effective.

“Additional reduction in deforestation is going to be very difficult,” he said. “Locals have to really feel they are part of the solution.”

The governor added that social issues are highly variable across different parts of Pará, so “solutions won’t be the same in all areas.”

“We need to reduce inequality and poverty,” he said. “Poor people will need to increase their footprint, while rich people must reduce their footprint.”

“And this applies globally,” he added, noting the consumption patterns of people in the United States which are many times higher than those in Pará.

Still, he reiterated, there is widespread support in Pará for curbing deforestation.

“The zero net deforestation goal for 2020 goal is not an idea from outside, it’s a demand from society. Most are in favor of reducing deforestation. There are some groups that want to continue deforesting but they are in the minority.”

He said proposed changes to Brazil’s Forest Code wouldn’t affect Pará’s 2020 commitment.

Jatene also highlighted an overlooked motivation for ending deforestation: an open frontier is expensive for governments.

“It makes sense for the government to push for a closed frontier,” he said. “When the frontier is open, the government has to extend services and infrastructure without getting the tax benefits because of illegality.”

“There are strong reasons for Pará to commit to zero net deforestation,” he said. “Pará can be an example for the rest of the world.”

Related articles