A team of scientists has created the first high resolution maps of remote forests in Madagascar. The effort, which is written up in the journal Carbon Balance and Management, will help more accurately register the amount of carbon stored in Madagascar’s forests, potentially giving the impoverished country access to carbon-based finance under the proposed REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) program.

The research was led by Greg Asner of the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology, whose team has developed advanced sensors that provide data on carbon and biodiversity from thousands of feet above the forest canopy. The GoodPlanet Foundation and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) also participated in the project, which mapped some 2.4 million hectares (9,160 square miles) using a combination of field data, airplane-based sensors, and satellite imagery.

To test the range of the technology, the scientists mapped two radically different regions: the humid tropical rainforests of the northern part of the country and an area which included desert-like “spiny” forest in the south. They were able to quantify carbon stocks across multiple ecosystems and vegetation types.

Madagascar with the 659,592 ha northern and 1,713,088 ha southern study regions. Courtesy of Asner et al. |

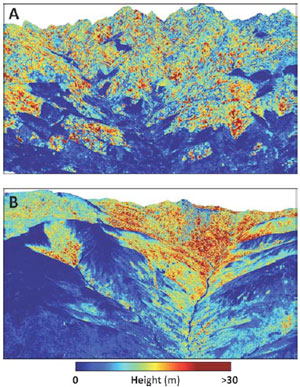

Example LiDAR-based maps of aboveground carbon stocks highlighting: (A) effects of deforestation on humid, low elevation forests in the northern region, and (B) a natural gradient in elevation and plant available water, from dry forests with low canopy height in the lowlands to humid forests in the uplands. |

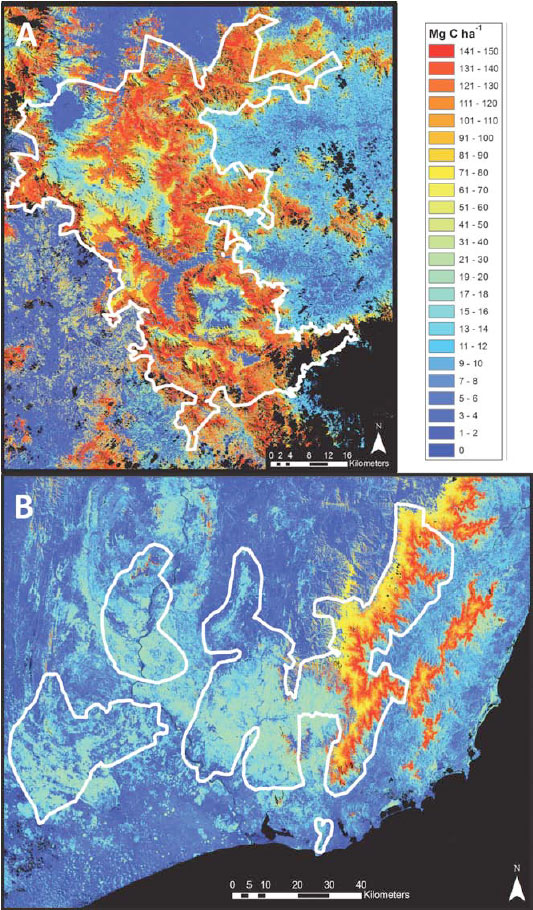

“We found that humid mountain forests had the highest carbon densities, while there was less carbon in dry forests and in the lowlands with more human activity,” said Asner in a prepared statement. “Despite widespread human activity, we found that large-scale natural controls over carbon stocks were heavily driven by the type of terrain and vegetation cover.”

Unsurprisingly the study found the highest levels of carbon in old-growth forests, which have lately been targeted by illegal loggers seeking precious hardwood timber like ebony and rosewood. Regrowing forests stored variable amounts of carbon.

Asner says the results show that carbon stocks can be accurately and rapidly quantified remotely once calibrated with on-the-ground fieldwork.

“These results show that we can obtain verifiable carbon assessments in remote tropical regions, which will be a boon not only to science and conservation, but to potential carbon-offset programs,” he added.

Madagascar presently has several REDD pilot projects, which aim to provide economic incentives for leaving forests standing. One project is run by GoodPlanet and WWF Madagascar in partnership with Air France.

Aboveground carbon density (ACD) across the (A) northern and (B) southern region of Madagascar. Median ACD reflects the median value for a habitat class as measured within the LiDAR coverage for that class. Black areas are unobserved or water bodies. |

CITATION: Asner et al.: Human and environmental controls over aboveground carbon storage in Madagascar. Carbon Balance and Management 2012 7:2.

Related articles

Laser-based forest mapping as accurate for carbon as on-the-ground plot sampling

(11/02/2011) Two new research papers show that an advanced laser-based system for forest monitoring is at least as accurate as traditional plot-based assessments when it comes to measuring carbon in tropical forests.

Breakthrough technology enables 3D mapping of rainforests, tree by tree

(10/24/2011) High above the Amazon rainforest in Peru, a team of scientists and technicians is conducting an ambitious experiment: a biological survey of a never-before-explored tract of remote and inaccessible cloud forest. They are doing so using an advanced system that enables them to map the three-dimensional physical structure of the forest as well as its chemical and optical properties. The scientists hope to determine not only what species may lie below but also how the ecosystem is responding to last year’s drought—the worst ever recorded in the Amazon—as well as help Peru develop a better mechanism for monitoring deforestation and degradation.