It took a custom-made submarine, billionaire Paul Allen, and a tenacious desire lasting well beyond two decades to unveil enigmatic details about the life of the coelacanth—the primitive fish that invariably hooks researchers.

A study published earlier this year in the journal Marine Biology summarizes 21 years of coelacanth population research by one team, led by Hans Fricke of the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, Germany. Working in the Indian Ocean off the African island nation of Comoros, Fricke documented a stable population of Latimeria chalumnae. However, his study notes that deep-set fishing nets could threaten these unique animals.

Hans Fricke with a caught coelacanth. Photo by: Raphael Plante

|

The last living relative of the coelacanth (“SEE-la-kanth”) disappeared 70 million years ago. The fish “returned” from its presumed extinction after fishermen captured one in 1938. This “living fossil” retains characteristics unlike those found in modern fish: hollow tail spines, fleshy fin bases, unique fin coordination, hinged skull, electroreceptor organ, and armored scales. Like some sharks, coelacanths bear live young.

Adult coelacanths can reach two meters long, but they are slowpokes; they hide in caves during the day and subsist on 12 grams of food daily. Because of their elusive behavior and depth range (150 to 700 meters), long periods pass between individual coelacanth sightings.

Fricke started the first long-term population assessment of coelacanths in 1986. During the survey, he identified 145 individuals by their unique spotting. By encountering the same colecanths throughout the study, he derived they lived far beyond previous age estimations, with an average lifespan of 103 years.

Fricke never observed reproduction, predation or juveniles, but believes the total Comoros population holds 300 to 400 individuals—a number he regards as viable.

“There are no data anywhere else on their population densities,” said Fricke in an interview with mongabay.com. “You need this if you want to gain insight into a population’s well-being.”

Using Fricke’s customized submersible JAGO for 115 dives, the team laboriously surveyed just 10 percent of potential habitat along 90 km of coastline. “This study will probably never be done again because of the cost,” Fricke said, noting the expense of shipping a submarine and hiring a surface vessel in an area rife with pirates.

“This is the magnum opus of their work done, and as such it’s a valuable summary,” said ecologist Mark Erdmann of Conservation International, who was not involved with the study. “It’s hard to get observations on these animals,” Erdmann told mongabay.com.

Though Fricke was surprised at never seeing juveniles during the study to date, Erdmann was not. Manned subs have fundamental restraints, notably observation time and maneuvering in tight spaces, that make it difficult to “look in small cracks and caves.” Japanese researchers discovered the first juvenile using a smaller remotely operated vehicle (ROV).

To explore potential juvenile and adult habitat deeper than Fricke’s census area, Paul Allen—the cofounder of Microsoft—lent his ROV to Fricke for three dives.

A coelacanth caught as by-catch in 1989 by local fishermen off the fishing village of Dzahadjou, Grande Comore. Photo by: Juergen Schauer / JAGO-Team |

With less fishing from traditional fishing galawas, coelacanth by-catches in Comoros are at their lowest: three to four per year. However, Erdmann and Fricke both fear that future fishing expansion may imperil these long-lived creatures. Nearshore fisheries are seriously depleted, and moving gill nets to deeper waters means potentially “wiping out the entire population within a short time,” Fricke said.

Though large chunks of the fish’s life history are still missing, Fricke said witnessing rare events such as reproduction would involve a stroke of luck. Instead, with Paul Allen’s help, he hopes to locate the original home of the coelacanth. “It is definitely not the Comoros,” he said. “It’s probably in the western Pacific, north of New Guinea.”

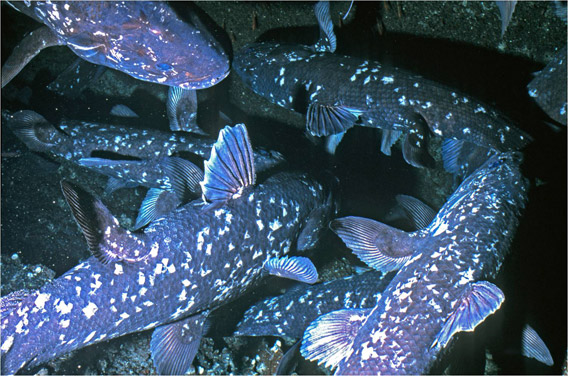

Underwater footage of adult coelacanths, taken by a team led by German marine biologist

Hans Fricke.

CITATION: Fricke H, Hissmann K, Froese R, Schauer J, Plante R, Fricke S (2011) The population biology of the living coelacanth studied over 21 years. Marine Biology 158 (7), pp. 1511-1522. DOI: 10.1007/s00227-011-1667-x

Amy E. West is a graduate student in the Science Communication Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz.