Forest loss along the edge of Mount Dongotomea in South Sudan is visible from Google Earth.

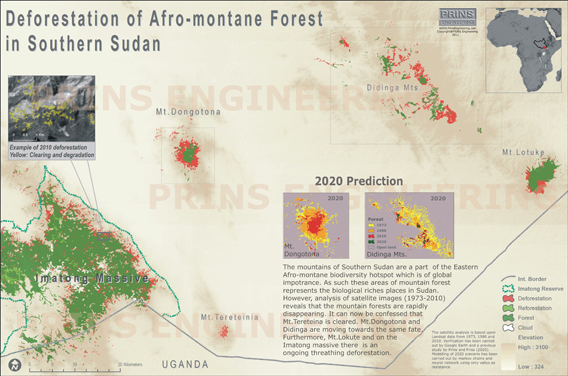

South Sudan’s tropical montane forests are fast disappearing according to new analysis by PRINS Engineering. At current rates, Mount Dongotomea, located in South Sudan’s most biodiverse ecosystem, could be completely stripped of tree cover by 2020.

The forests of the Imatong Mountains, rising to 10,456 feet (3,187 meters), i in southern South Sudan are part of the Eastern Afro-montane ecosystem, rated by scientists as one of Africa’s biodiversity hotspots. Although the afro-montane forests reach only into limited areas of South Sudan, they offer the soon-to-be new country an estimated half of its plant biodiversity. These forests are home to many endemic and possibly unique species, but scientists have yet to study the region’s species.

The Imatong forests have been heavily degraded and deforested, and Mount Dongotomea is now bearing the brunt of clearing that threatens to fragment the ecosystem further. The mountain’s tree cover has been reduced by two-thirds since 1986, and, if deforestation in the area continues, the forests of Mount Dongotomea will also disappear before the end of the decade.

Northeast of Mount Dongotomea, the Didinga hills were largely cleared by 1986, and in 2010 small farmers continued deforesting the eastern side of Mount Dongotomea.

The Imatong Mountains are critical to Africa’s biodiversity, yet also crucial to the economic development of South Sudan. Deforestation in Sudan is mainly driven by the harvesting of woodfuels and other subsistence needs, and people’s survival will be jeopardized further should the region’s forests be cleared and its resources entirely lost.

PRINS relates that the new Minister of Wildlife of Eastern Equatoria state, South Sudan, is interested in local conservation, but needs more funding. In addition, for the government to protect forests and manage natural resources sustainably, detailed maps of land use patterns and botanical habitats will be needed to create a management plan to protect these forest islands.

Map of deforestation in the South Sudan tropical mountain forests. Click to enlarge.

Related articles

Foreign big agriculture threatens world’s second largest wildlife migration

(03/07/2011) As the world’s largest migration in the Serengeti plains—including two million wildebeest, zebra, and Thomson’s gazelles—has come under unprecedented threat due to plans for a road that would sever the migration route, a far lesser famous, but nearly as large migration, is being silently eroded just 1,370 miles (2,200 kilometers) north in Ethiopia’s Gambela National Park. The migration of over one million white-eared kob, tiang, and Mongalla gazelle starts in the southern Sudan but crosses the border into Ethiopia and Gambela where Fred Pearce at Yale360 reports it is running into the rapid expansion of big agribusiness. While providing habitat for the millions of migrants, Gambela National Park’s land is also incredibly fertile enticing foreign investment.

South Sudan’s choice: resource curse or wild wonder?

(02/11/2011) After the people of South Sudan have voted overwhelmingly for independence, the work of building a nation begins. Set to become the world’s newest country on July 9th of this year, one of many tasks facing the nation’s nascent leaders is the conservation of its stunning wildlife. In 2007, following two decades of brutal civil war, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) surveyed South Sudan. What they found surprised everyone: 1.3 million white-eared kob, tiang (or topi) antelope and Mongalla gazelle still roamed the plains, making up the world’s second largest migration after the Serengeti. The civil war had not, as expected, largely diminished the Sudan’s great wildernesses, which are also inhabited by buffalo, giraffe, lion, bongo, chimpanzee, and some 8,000 elephants. However, with new nationhood comes tough decisions and new pressures. Multi-national companies seeking to exploit the nation’s vast natural resources are expected to arrive in South Sudan, tempting them with promises of development and economic growth, promises that have proven uneven at best across Africa.

‘Land grab’ fears in Africa legitimate

(01/31/2011) A new report by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) has found that recent large-scale land deals in Africa are likely to provide scant benefit to some of the world’s poorest and most famine-prone nations and will probably create new social and environmental problems. Analyzing 12 recent land leasing contracts investigators found a number of concerns, including contracts that are only a few pages long, exclusion of local people, and in one case actually give land away for free. Many of the contracts last for 100 years, threatening to separate local communities from the land they live on. “Most contracts for large-scale land deals in Africa are negotiated in secret,” explains report author Lorenzo Cotula in a press release. “Only rarely do local landholders have a say in those negotiations and few contracts are publicly available after they have been signed.”