The proposed revision of Brazil’s Forest Code could prevent the country from meeting its lower emissions target and is unlikely to ease rural poverty, concludes a new study by the Brazil-based Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA).

BR>

Last month Brazil’s lower parliamentary house approved, by a 410-63 vote, a bill to revise the Forest Code, one of the country’s strongest pieces of environmental legislation. The legislation is currently being debated in Brazil’s Senate. Should it pass there, President Dilma Rousseff would then decide whether to sign the bill into law.

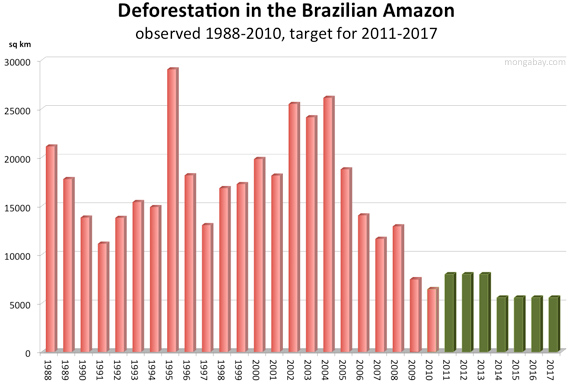

As it currently stands, the bill would reduce the percentage of land a private landowner is required to maintain as forest. Landowners who deforested before July 2008 would be absolved of the need to reforest illegally cleared land. These provisions could undermine Brazil’s 2009 vow to reduce deforestation 80 percent and greenhouse gas emissions 39 percent from a projected baseline by 2020. To meet these emissions targets, Brazil must cut 1 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent annually. But two-thirds of these emissions cuts are supposed to come from reduced deforestation, which is now jeopardized by Forest Code revisions.

Undercutting climate and deforestation commitments

A recent study by Brazil’s Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA) finds that if the Forest Code revisions are passed, Brazil’s emissions and deforestation targets will go unmet.

Farmers and responsible for illegally clearing nearly 30 million hectares (74 million acres) of Amazon rainforest would be granted amnesty and, in addition, would no longer have to reforest cleared lands. But Fabio Alves, an expert with IPEA, told Bloomberg News that Brazilian ranchers have cleared 159 million hectares of legally protected forest. If this area were replanted, he estimates 18.6 billion tons of carbon dioxide would be sequestered, and Brazil could meet its Copenhagen commitments for the next 18 years.

Legal reserves—preserved areas on private lands—are key components of Brazil’s conservation system. However, the changes to the Forest Code threaten these privately-held reserves. Combined, legal reserves comprise more forested land than state and local conservation units (largely equivalent to national parks and forests in the US). According to the IPEA study, not enough unclaimed land exists in the Amazon for the creation of new conservation units, making the legal reserves essential for the conservation of biodiversity because they serve as habitat corridors connecting large tracts of government-protected forests.

Expectations that Forest Code revisions will pass the Senate, along with the anticipation of amnesty for illegal clearcutting, already has resulted in a sudden spike in deforestation. Illegal logging has quadrupled in the Amazonian state of Mato Grosso, and is “out of control” in the southern Amazon according to Marina Silva, a former Green Party presidential candidate and environmental minister, who was interviewed by Bloomberg News.

Silva, a personal friend of assassinated environmentalist Chico Mendes, also told Bloomberg News that the revised Forest Code would make Brazil’s commitments to reduce deforestation “fragile.” She asserted that Brazil must commit to sustainable development to secure an international leadership role.

“We can’t permit the national environmental system to be deconstructed,” warned Silva, who grew up tapping rubber in the Amazon, “Today we have state and municipalities wanting to transfer a good part of the responsibility to protect forests to the state and municipalities, and in my opinion this would weaken (environmental protection) completely.”

Reducing deforestation in the Amazon 80 percent by 2020 would prevent 564 million tons of CO2 from being released, according to the IPEA.

But will the proposals successfully fight rural poverty?

Politicians who support the changes argue that the new Forest Code would better combat rural poverty in the Amazon. Rural poverty is a significant issue in the region due in part to extreme land inequality. Brazil’s National Rural Registration System (SNCR), which measures landholdings using “fiscal models,” reports that small farms represent 90 percent of Brazil’s rural properties, but occupy only 24 percent of rural land area. minifúndios, which the IPEA defines as farms small enough that they are highly unlikely to be able to support a family, comprise 65 percent of rural properties in Brazil, yet represent only 8 percent of rural land area. In contrast, while Brazil’s large properties account for only 3 percent of rural owners, they occupy 56 percent of rural land area.

A 2006 agricultural census conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) revealed a Gini index for land distribution of .872, the Gini coefficient measures inequality of distribution and is a number between 0 and 1, with 1 representing complete inequality.

Aldo Rebelo, the senator who has led the charge to weaken the country’s 1965 Forest Code, claims that the current Forest Code prevents small farmers from expanding their farming activities enough to lift themselves out of poverty. The IPEA study disagrees. It finds that the 3.4 million minifúndios, which comprise 48.3 million hectares, would need an additional 76 million additional hectares to lift their occupants out of poverty and guarantee minimal economical security. But the study found that clearing the legal reserves on minifúndios –permissible under proposed Forest Code revisions—would free up only 17 million hectares, or less than a quarter of what would be required. Instead of revising the Forestry Code, development experts Michael Todaro and Stephen Smith say extensive land reform will be needed to tackle rural poverty effectively.

Marina Silva argues that the government can aid those in poverty through a number of ways more effective than legalizing deforestation. “Family farmers want the government to have policies to help them comply with the law, because the majority want to comply with the law, and so they need technical assistance, incentives, credit, so they can…use fewer and fewer natural resources,” she told Bloomberg News.

The IPEA study points out that legal reserves offer benefits to farmers: forests prevent soil erosion, offer opportunities for the extraction of forest resources to supplement food or income, and host pollinators crucial to crop reproduction.

In addition, the revised Forest Code would punish those who have followed the letter of the law, according to IPEA, and reward those who have not. For example, if current legislation were better enforced, a potential buyer would prefer to purchase a farm 80 percent forested (in compliance with the 1965 Forest Code) in order to avoid the costs of reforesting the land to comply with the law. However, if the Forest Code revisions pass, buyers would likely tilt toward purchasing already-cleared landholdings to avoid having to clear the land themselves.. Farmers with forested land would then be at a disadvantage, and perhaps deforest their lands.

“We’re in the 21st century. Today we know that we have to protect natural resources bases for our development, and we know that we have to protect those who are the true guardians of these natural resources bases—the Indians, rubber tappers, and in the reality of Brazil, the traditional populations….It’s fundamental that we create an equality of opportunity, a place for all in the development of Brazil,” said Silva.

CITATION: Todaro, Michael and Stephen Smith. Economic Development. Boston: Pearson Addison Wesley, 2009.

Related articles