Oil palm plantations, peatland, and forest in Sarawak. Courtsy of Google Earth.

Peatlands and rainforests in Malaysia’s Sarawak state on the island of Borneo are being rapidly destroyed for oil palm plantations, according to new studies by environmental group Wetlands International and remote sensing institute Sarvision.

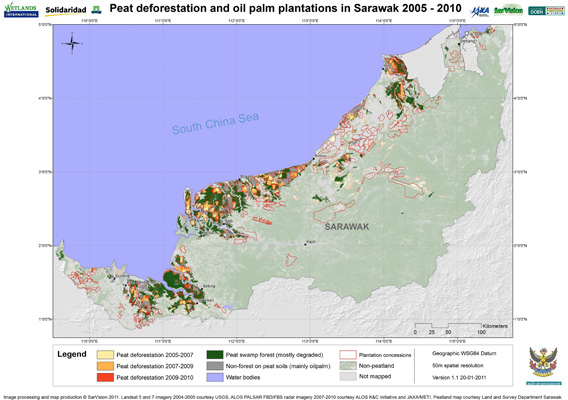

The analysis shows that more than one third (353,000 hectares or 872,000 acres) of Sarawak’s peatswamp forests and ten percent of the state’s rainforests were cleared between 2005 and 2010. About 65 percent of the area was converted for oil palm, which is replacing logging as timber stocks have been exhausted by unsustainable harvesting practices.

“As the timber resource has been depleted the timber companies are now engaging in the oil palm business, completing the annihilation of Sarawak’s peat swamp forests,” said Marcel Silvius, a senior scientist at Wetlands International.

The research, based on field surveys and satellite data, found that 20 percent of all Malaysian palm oil is produced on drained peatlands. In Sarawak, the rate is 44 percent.

Wetlands International says the studies are important because Malaysia does not provide “verifiable information on land use in relation to soil type or deforestation.”

“Official Malaysian government figures now appear to have given a far too optimistic picture; stating that only 8-13% of Malaysia’s palm oil plantations were situated on carbon rich peat soils; 20% for Sarawak,” the group said in a press release.

“This is the first time that detailed and verified figures on deforestation and peatswamp conversion come available for Sarawak,” added Niels Wielaard of Sarvision. “Free availability of satellite imagery and tools such as Google Earth are revolutionizing forest monitoring.”

Click here for a large version of this map

The results come three months after Sarawak announced it would double its oil palm estate over the next decade. Speaking to The Star last November, James Masing, State Land Development Minister, said Sarawak is targeting 2 million hectares by 2020, which would make it the country’s largest palm oil producer. Sarawak presently has around 920,000 hectares of oil palm plantations.

But expansion raises a number of social and environmental concerns. New plantings have sparked conflict between developers and traditional forest users like the Penan, an indigenous group comprised of a number of sub-groups, a handful of which may remain nomadic. The Sarawak government says it intends to specific target lands claimed by native people, chiefly because native customary rights land cover an estimated 1.5 million hectares of the state.

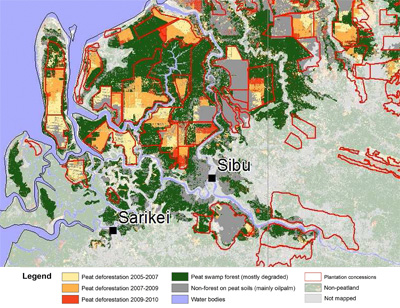

Close up on the Wetlands International/Sarvision map |

Conversion of peatlands for palm oil production worries environmentalists because the process triggers large greenhouse gas emissions through both deforestation and drainage of the carbon-dense peat. Degraded peatlands are also more vulnerable to fire. Wetlands estimates that Malaysia’s palm oil industry is responsible for a minimum of 20 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually.

“However, twice this amount is more likely,” said the group.

Peat forests lands are also a refuge for some of Malaysia’s most threatened species including the Borneo Pygmy elephant (Elephas maximus borneensis), the Sumatran Rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), the Bornean Clouded Leopard (Neofelis diardi borneensis), the Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus), the Proboscis Monkey (Nasalis larvatus), the Storm’s Stork (Ciconia stormi), the False Gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii) and the Painted terrapin (Batagur borneoensis).

Despite these concerns, planned expansion may be difficult to slow. Malaysia’s federal system means that Sarawak can largely ignore mandates issued in the capital. Meanwhile, logging and plantations companies enjoy close ties with the state’s chief minister Abdul Taib Mahmud, who has ruled since 1981 and has accumulated great wealth despite a earning a civil servant’s wage. Recent investigations have linked tens of millions of dollars’ worth property holdings in the United States and Canada to Taib’s family.

Wetlands International believes pressure can be applied from the consumption side. It says consumers should question the origin of palm oil used in the products they buy and policy makers in Europe should include strong safeguards for sourcing of biofuels to ensure they do not drive deforestation and peatlands destruction.

Sensing the risks, some Malaysian palm oil producers have joined the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a body that sets environmental and social certification criteria. The RSPO aims to distinguish ostensibly responsible producers, but especially egregious transgressions by bad actors have tended to tarnish the image of the whole sector in the eyes of international consumers.

Related articles

Greening the world with palm oil?

(01/26/2011) The commercial shows a typical office setting. A worker sits drearily at a desk, shredding papers and watching minutes tick by on the clock. When his break comes, he takes out a Nestle KitKat bar. As he tears into the package, the viewer, but not the office worker, notices something is amiss—what should be chocolate has been replaced by the dark hairy finger of an orangutan. With the jarring crunch of teeth breaking through bone, the worker bites into the “bar.” Drops of blood fall on the keyboard and run down his face. His officemates stare, horrified. The advertisement cuts to a solitary tree standing amid a deforested landscape. A chainsaw whines. The message: Palm oil—an ingredient in many Nestle products—is killing orangutans by destroying their habitat, the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra.

Orangutans vs palm oil in Malaysia: setting the record straight

(01/16/2010) The Malaysian palm oil industry has been broadly accused of contributing to the dramatic decline in orangutan populations in Sabah, a state in northern Borneo, over the past 30 years. The industry has staunchly denied these charges and responded with marketing campaigns claiming the opposite: that oil palm plantations can support and nourish the great red apes. The issue came to a head last October at the Orangutan Colloquium held in Kota Kinabalu. There, confronted by orangutan biologists, the palm oil industry pledged to support restoring forest corridors along rivers in order to help facilitate movement of orangutans between remaining forest reserves across seas of oil palm plantations. Attending NGOs agreed that they would need to work with industry to find a balance that would allow the ongoing survival of orangutans in the wild. Nevertheless the conference was still marked by much of the same rhetoric that has characterized most of these meetings — chief palm oil industry officials again made dubious claims about the environmental stewardship of the industry. However this time there was at least acknowledgment that palm oil needs to play an active role in conservation.

Consumers should help pay the bill for ‘greener’ palm oil

(01/12/2010) Palm oil is one of the world’s most traded and versatile agricultural commodities. It can be used as edible vegetable oil, industrial lubricant, raw material in cosmetic and skincare products and feedstock for biofuel production. Growing global demand for palm oil and the ensuing cropland expansion has been blamed for a wide range of environmental ills, including tropical deforestation, peatland degradation, biodiversity loss and CO2 emissions. In response to these concerns, a group of stakeholders—including activists, investors, producers and retailers—formed the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to develop a certification scheme for palm oil produced through environmentally- and socially-responsible ways. It is widely anticipated that the creation of a premium market for RSPO-certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) would incentivize palm oil producers to improve their management practices.

Misleading claims from a palm oil lobbyist

(10/23/2010) In an editorial published October 9th in the New Straits Times (“Why does World Bank hate palm oil?”), Alan Oxley, a former Australian diplomat who now serves as a lobbyist for logging and plantation companies, makes erroneous claims in his case against the World Bank and the International Finance Corp (IFC) for establishing stronger social and environmental criteria for lending to palm oil companies. It is important to put Mr. Oxley’s editorial in the context of his broader efforts to reduce protections for rural communities and the environment.