Oil palm and logged over rainforest in Sabah, Malaysia. Photo by Rhett A. Butler 2008.

One of the world’s highest profile and most controversial palm oil companies, Golden Agri-Resources Limited (GAR), has signed an agreement committing it to protect tropical forests and peatlands in Indonesia. The deal—signed with The Forest Trust, an environmental group that works with companies to improve their supply chains—could have significant ramifications for how palm oil is produced in the country, which is the world’s largest producer of palm oil.

GAR owns PT Sinar Mas Agro Resources and Technology (SMART), a firm that has been aggressively targeted by Greenpeace and other environmental activists for destruction of rainforests and peatlands in Borneo. The campaigns cost SMART dearly, with the company suffering a wave of customer defections, including Unilever, Kraft, Nestle, Burger King, and General Mills, among others. SMART exacerbated its woes by misrepresenting the results of an independent audit of its operations and hiring marketing firms and lobby groups to make dubious claims about its environmental performance. SMART was subsequently threatened with expulsion from the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, a body that sets social and environmental criteria for palm oil production.

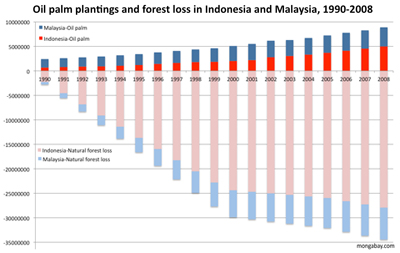

Expansion of the oil palm estate and natural forest loss in Indonesia and Malaysia, 1990-2008. Click image to enlarge |

The new agreement offers SMART and GAR a path toward redemption. GAR will establish a forest conservation policy that bans development of peatlands and high carbon stock and high conservation value (HCV) forests. The policy also includes social safeguards including free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) for indigenous and local communities as well as compliance with Indonesian laws and RSPO Principles and Criteria. The policy will apply for all plantations GAR owns, manages, or invests in.

GAR, which has 433,000 hectares of oil palm plantations and is the world’s second largest producer of palm oil, said it will promote the policy across the palm oil industry.

“We will leverage our leadership position and advocate this policy in partnership with the Indonesian and global community,” the company said in a statement.

GAR’s partner in developing and monitoring the policy said the agreement could have global implications for the world’s forests, which are increasingly at risk from commodity production, rather than subsistence farming, as was once the case.

“Today’s agreement represents a revolutionary moment in the drive to conserve forests,” said Scott Poynton, TFT’s executive director, in a statement. “It’s about going to the root causes of deforestation; we have shown that the destruction of forests is anchored deeply in the supply chains of the products we consume in industrialized nations and we are showing we can do something about that.”

TFT’s engagement with GAR arose out of uproar generated by a Greenpeace campaign over Nestle’s use of palm oil in its KitKat bar. The campaign included a video showing an office worker biting into the finger of an orangutan, implying that Nestle’s palm oil—which came from SMART—was contributing to destruction of orangutan habitat. After some critical misteps, Nestle announced it would implement a new sourcing policy for palm oil. |

Franky Wijaya, Chairman and CEO of GAR, said the deal would help put Indonesia on a more sustainable development path for growing its economy.

“As a leading player in the palm oil industry, we are committed to playing our role in conserving Indonesia’s forests and look forward to working with all stakeholders including the Government of Indonesia, other key players in the palm oil industry, NGOs and the local communities, to find the common ground for sustainable palm oil production,” Wijaya said in a statement. “Our partnership with TFT allows us to grow palm oil in ways that conserve forests and that also respond to Indonesia’s development needs; creating much needed employment while building shareholder value.”

Even GAR’s fiercest critic, Greenpeace Indonesia, is cautiously optimistic about the announcement.

“Leadership of GAR is important to make other player’s believe this is good for Indonesia’s economy and business,” Bustar Maitar, Forest campaigner for Greenpeace Southeast Asia, told mongabay.com. “There no choice for other producers but to move toward higher standards of palm oil production. Producers can no longer say ‘no’ to saving Indonesian forests. GAR is already committed to making a profit without destroying forest, so I believe other companies can also do it.”

Ensuring GAR abides by its commitment

The Forest Trust (TFT) says it will working closely with a range of stakeholders to ensure GAR upholds its commitment.

|

|

“We all know that this agreement counts for nothing if it’s not now implemented,” Poynton said in a statement. “The process has begun already with TFT experts visiting GAR plantations, and we have funding from the company and a clear action plan for making sure this agreement sticks. We have worked with other companies to clean up their supply chains successfully, and it is our intention to do so again. We are confident we will be able to overcome any concerns about whether this agreement will lead to substantive change.”

Poynton told mongabay.com that local NGOs, including rights’ groups and environmental organizations, will be the “eyes and ears” to help ensure GAR’s pledges are implemented. He also noted that TFT will conduct site visits on an ongoing basis.

Greenpeace’s Maitar said the government would have a role to play as well.

“Participation of other stakeholders is important,” he told mongabay. “Government should play a key role in law enforcement and for sure civil society is important to monitor, together with the local community, what is going on the ground.”

“The partnership is good signal for moving forward to address deforestation, but this is still on paper,” he continued. “Greenpeace wants to see this commitment implemented on the ground, but so far we are seeing there is a serious effort by GAR to move forward with this.”

The palm oil paradox

Palm oil is now found in up to half of packaged processed foods in some markets. By virtue of its high yield, palm oil is a cheaper substitute than other vegetable oils. In an effort to reduce costs, some candymakers are using palm oil in place of cocoa butter in their milk chocolate products. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

Palm oil is used widely in processed foods, cosmetics, and soaps — WWF estimates that palm oil is found in roughly half of packaged supermarket products. It is also increasingly used as a biofuel.

Over the past twenty years, palm oil has emerged as a economic juggernaut in Indonesia and Malaysia. With its high yield, oil palm is an astoundingly profitable crop and accordingly, plantations have spread across Sumatra, Borneo, New Guinea, and other islands, taking a heavy toll on forests. By some estimates, more than half of oil palm expansion since 1990 occurred at the expense of forests, spurring strong backlash from environmentalists concerned about greenhouse gas emissions and loss of habitat for endangered wildlife—including orangutans, pygmy elephants, Sumatran rhinos and tigers. Oil palm plantation development has also exacerbated social conflict in some areas.

Related articles

Greening the world with palm oil?

(01/26/2011) The commercial shows a typical office setting. A worker sits drearily at a desk, shredding papers and watching minutes tick by on the clock. When his break comes, he takes out a Nestle KitKat bar. As he tears into the package, the viewer, but not the office worker, notices something is amiss—what should be chocolate has been replaced by the dark hairy finger of an orangutan. With the jarring crunch of teeth breaking through bone, the worker bites into the “bar.” Drops of blood fall on the keyboard and run down his face. His officemates stare, horrified. The advertisement cuts to a solitary tree standing amid a deforested landscape. A chainsaw whines. The message: Palm oil—an ingredient in many Nestle products—is killing orangutans by destroying their habitat, the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra.

Consumers should help pay the bill for ‘greener’ palm oil

(01/12/2010) Palm oil is one of the world’s most traded and versatile agricultural commodities. It can be used as edible vegetable oil, industrial lubricant, raw material in cosmetic and skincare products and feedstock for biofuel production. Growing global demand for palm oil and the ensuing cropland expansion has been blamed for a wide range of environmental ills, including tropical deforestation, peatland degradation, biodiversity loss and CO2 emissions. In response to these concerns, a group of stakeholders—including activists, investors, producers and retailers—formed the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to develop a certification scheme for palm oil produced through environmentally- and socially-responsible ways. It is widely anticipated that the creation of a premium market for RSPO-certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) would incentivize palm oil producers to improve their management practices.

Indonesian climate official: palm oil lobbyist is misleading the public

(12/29/2010) Alan Oxley, a lobbyist for industrial forestry companies in the palm oil and pulp and paper sectors, is deliberately misleading the public on deforestation and associated greenhouse gas emissions, said a top Indonesian climate official.

Will Indonesia’s big REDD rainforest deal work?

(12/28/2010) Flying in a plane over the Indonesian half of the island of New Guinea, rainforest stretches like a sea of green, broken only by rugged mountain ranges and winding rivers. The broccoli-like canopy shows little sign of human influence. But as you near Jayapura, the provincial capital of Papua, the tree cover becomes patchier—a sign of logging—and red scars from mining appear before giving way to the monotonous dark green of oil palm plantations and finally grasslands and urban areas. The scene is not unique to Indonesian New Guinea; it has been repeated across the world’s largest archipelago for decades, partly a consequence of agricultural expansion by small farmers, but increasingly a product of extractive industries, especially the logging, plantation, and mining sectors. Papua, in fact, is Indonesia’s last frontier and therefore represents two diverging options for the country’s development path: continued deforestation and degradation of forests under a business-as-usual approach or a shift toward a fundamentally different and unproven model based on greater transparency and careful stewardship of its forest resources.

Logging, palm oil giant hires U.S. ambassador as lobbyist

(12/09/2010) Sinar Mas Group, the sprawling Indonesian conglomerate that has interests in coal mining, logging and wood-pulp production, palm oil plantations, real estate, and other industries, has hired Cameron Hume, the former U.S. ambassador to Indonesia, as an adviser, according to Detik.com. Ambassador Hume stepped down from his post at the embassy in August.

Nobel Prize winner, anti-poverty group, scientists fire back at logging lobbyist

(11/01/2010) An industrial lobbyist is facing mounting criticism for his campaign to reduce social and environmental safeguards in Indonesia.

Scientists blast greenwashing by front groups

(10/27/2010) A group of prominent scientists has published an open letter challenging the objectivity of World Growth International, an NGO that claims to operate on behalf of the world’s poor, and its leader Alan Oxley, a former trade diplomat who also chairs ITS Global, a marketing firm. The letter, published online in several forums, slams World Growth and ITS Global as a front groups for forestry companies. The scientists note that while the groups have not disclosed their sources of funding, they assert ITS receives funding from Sinar Mas, an Indonesian conglomerate that controls Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), a forest products brand, and Sinar Mas Agro Resources & Technology, a palm oil firm, among other companies.

Misleading claims from a palm oil lobbyist

(10/23/2010) In an editorial published October 9th in the New Straits Times (“Why does World Bank hate palm oil?”), Alan Oxley, a former Australian diplomat who now serves as a lobbyist for logging and plantation companies, makes erroneous claims in his case against the World Bank and the International Finance Corp (IFC) for establishing stronger social and environmental criteria for lending to palm oil companies. It is important to put Mr. Oxley’s editorial in the context of his broader efforts to reduce protections for rural communities and the environment.

Corporations, conservation, and the green movement

(10/21/2010) The image of rainforests being torn down by giant bulldozers, felled by chainsaw-wielding loggers, and torched by large-scale developers has never been more poignant. Corporations have today replaced small-scale farmers as the prime drivers of deforestation, a shift that has critical implications for conservation. Until recently deforestation has been driven mostly by poverty—poor people in developing countries clearing forests or depleting other natural resources as they struggle to feed their families. Government policies in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s had a multiplier effect, subsidizing agricultural expansion through low-interest loans, infrastructure projects, and ambitious colonization schemes, especially in the Amazon and Indonesia. But over the past two decades, this has changed in many countries due to rural depopulation, a decline in state-sponsored development projects, the rise of globalized financial markets, and a worldwide commodity boom. Deforestation, overfishing, and other forms of environmental degradation are now primarily the result of corporations feeding demand from international consumers. While industrial actors exploit resources more efficiently and cause widespread environmental damage, they also are more sensitive to pressure from consumers and environmental groups. Thus in recent years, it has become easier—and more ethical—for green groups to go after corporations than after poor farmers.

Malaysia/Indonesia partnership proposed to counter environmental complaints over palm oil

(10/18/2010) Malaysia and Indonesia should establish “a joint council based in Europe and the United States” to boost the image of palm oil and counter criticism from environmental and human rights groups, a Malaysian minister told Malaysia state press.

The Nestlé example: how responsible companies could end deforestation

(10/06/2010) The NGO, The Forest Trust (TFT), made international headlines this year after food giant Nestlé chose them to monitor their sustainability efforts. Nestlé’s move followed a Greenpeace campaign that blew-up into a blistering free-for-all on social media sites. For months Nestle was dogged online not just for sourcing palm oil connected to deforestation in Southeast Asia—the focus of Greenpeace’s campaign—but for a litany of perceived social and environmental abuses and Nestlé’s reactions, which veered from draconian to clumsy to stonily silent. The announcement on May 17th that Nestlé was bending to demands to rid its products of deforestation quickly quelled the storm. Behind the scenes, Nestlé and TFT had been meeting for a number of weeks before the partnership was made official. But can TFT ensure consumers that Nestlé is truly moving forward on cutting deforestation from all of its products?

Compliance with national law not enough to meet int’l market demands

(10/05/2010) A UK-based cosmetics firm is severing ties with its palm oil supplier after a story in The Observer reported the Colombia-based company sought the eviction of peasant farmer families to develop a new oil palm plantation, reports the Guardian.

(08/19/2010) Sinar Mas, an Indonesian conglomerate whose holdings include Asia Pulp and Paper, a paper products brand, and PT Smart, a palm oil producer, was sharply rebuked Wednesday over a recent report where it claimed not to have engaged in destruction of forests and peatlands. At least one of its companies, Golden Agri Resources, may now face an investigation for deliberately misleading shareholders in its corporate filings.

How Greenpeace changes big business

(07/22/2010) Tropical deforestation claimed roughly 13 million hectares of forest per year during the first half of this decade, about the same rate of loss as the 1990s. But while the overall numbers have remained relatively constant, they mask a transition of great significance: a shift from poverty-driven to industry-driven deforestation and geographic consolidation of where deforestation occurs. These changes have important implications for efforts to protect the world’s remaining tropical forests in that environmental groups now have identifiable targets that may be more responsive to pressure on environmental concerns than tens of millions of impoverished rural farmers. In other words, activists have more leverage than ever to impact corporate behavior as it relates to deforestation. A prime example of this power is evident in a string of successful Greenpeace campaigns, which have targeted some of the largest drivers of deforestation, including the palm oil industry in Indonesia and Malaysia and the soy and cattle industries in the Brazilian Amazon. The campaigns have shared a common approach: target large, conspicuous consumer-facing companies that sell in western markets.

Nestle caves to activist pressure on palm oil

(05/17/2010) After a two month campaign against Nestle for its use of palm oil linked to rainforest destruction spearheaded by Greenpeace, the food giant has given in to activists’ demands. The Swiss-based company announced today in Malaysia that it will partner with the Forest Trust, an international non-profit organization, to rid its supply chain of any sources involved in the destruction of rainforests. “Nestle’s actions will focus on the systematic identification and exclusion of companies owning or managing high risk plantations or farms linked to deforestation,” a press release from the company reads, adding that “Nestle wants to ensure that its products have no deforestation footprint.”

Nestle’s palm oil debacle highlights current limitations of certification scheme

(03/26/2010) Last week Nestle, the world’s largest food processor, was caught in a firestorm when it attempted to censor a Greenpeace campaign that targeted its use of palm oil sourced from a supplier accused of environmentally-damaging practices. The incident brought the increasingly raucous debate over palm oil into the spotlight and renewed questions over an industry-backed certification scheme that aims to improve the crop’s environmental performance.

A new world?: Social media protest against Nestle may have longstanding ramifications

(03/20/2010) The online protest over Nestle’s use of palm oil linked to deforestation in Indonesia continues unabated over the weekend. One only needed to check-in on the Nestle’s Facebook fan page to see that anger and frustration over the company’s palm oil sourcing policies, as well as its attempts to censor a Greenpeace video (and comments online), has sparked a social media protest that is noteworthy for its vehemence, its length, and its bringing to light the issue of palm oil and deforestation to a broader public.

Blackwashing by NGOs, greenwashing by corporations, threatens environmental progress

(11/12/2009) Misinformation campaigns by both corporations and environmental groups threaten to undermine efforts to conserve biodiversity and reduce environmental degradation, argues a new paper published in the journal Biotropica. Growing concerns over climate change and unsustainable resource extraction have put companies that exploit the environment in the spotlight. Some firms have responded by taking measures to reduce their environmental impact. Others have alternatively engaged in sophisticated marketing campaigns intended to mislead consumers on their environmental performance, maintaining that environmentally-destructive practices are instead benign. At the same time some activist groups have been guilty of exaggerating claims of environmental misconduct in order to boost support for their campaigns and therefore their fundraising efforts.