Many credit Brazil’s 75-year old Forest Code with helping to slow destruction of the Amazon Rainforest, but an unlikely amalgamation of right-wing and left-wing politicians are trying to gut the law. In this first of two articles, Ecosystem Marketplace examines the state of the debate. In the second part, Ecosystem Marketplace takes a look at the law’s implications for the Amazon – and for the forest-carbon marketplace in Brazil.

“Farms Here, Forests There!”

It’s a catchphrase that was recently rolled out by Avoided Deforestation Partners (ADP) to drum up support for carbon payments that reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) in the now-sidelined American Power Act.

We can help to stop deforestation in the Amazon, the campaign argued, while bettering the situation for farmers here in the US.

Click to enlarge |

That same sloganeering recently found its way to Brazil, where people like Communist Party federal deputy Aldo Rebelo picked it up. For Rebelo and his allies, however, “Farms Here, Forests There” has an altogether different meaning: to them, the phrase means “rainforest conservation at the expense of Brazilian farmers.”

In fact, Rebelo and his allies in the ruralista bloc are determined to weaken the Código Florestal, Brazil’s environmentally progressive Forest Code. Ironically, Rebelo and his supporters have used ADP’s pro-conservation slogan to whip up support for their anti-conservation campaign.

And their efforts have paid off: By recasting their attack on the Forest Code as a nationalist response to unfair international pressures for conservation in Brazil, the opponents of the Forest Code have been winning the public relations war. In July, they managed to push a far-reaching reform proposal through the Special Committee on the Forest Code in the Chamber of Deputies.

Forest Code Under Fire

Passage of the amendment caused an uproar among both environmentalists and scientists in Brazil. First passed in 1934, Brazil’s Forest Code has been strengthened in recent years and is considered one of the world’s most progressive forest policies. Supporters of the Forest Code say it has played a major role in the rapid deceleration of deforestation rates in the Amazon over the last decade.

In a letter in the July 16 issue of Science, six Brazilian scientists wrote that the new rules “will benefit sectors that depend on expanding frontiers by clear-cutting forests and savannas and will reduce mandatory restoration of native vegetation illegally cleared since 1965.”

Farms Here, Forests There |

The scientists warn that carbon CO2 emissions “may increase substantially,” and as many as 100,000 species might be put at risk of extinction if the proposal becomes law. “Under the new Forest Act,” the scientists said, “Brazil risks suffering its worst environmental setback in half a century, with critical and irreversible consequences beyond its borders.”

Will the Reform Bill Become Law?

Advocates for reducing deforestation say the proposed changes run counter to Brazil’s recent successes and officially promulgated goals for reducing Brazil’s green house gas emissions. But the reform bill still has some way to go before it actually becomes law.

First, the full Chamber of Deputies would need to pass it. After that, the Senate, which is the second body in Brazil’s bicameral legislature, would also need to vote on it.

If passed in the legislature, however, the bill would then move forward to President Lula, who is constitutionally barred from seeking a third term in this October’s presidential and national elections. The post-election lame-duck session would make it difficult for Lula to oppose the reform bill, especially if opponents of the Forest Code gain seats in the legislature. If not vetoed, Lula’s successor could then implement the bill.

Opponents of the Forest Code

Behind the current proposal for Forest Code reform is an unlikely but imposing alliance: leftist politicians like Rebelo, the rapporteur who led the bill through committee, and the traditionally conservative ruralista coalition, which has close ties to traditional agriculture.

Moreover, the combination of an election season followed by a lame-duck session may create a perfect storm in which the Forest Code reform bill might actually pass.

Raul do Valle Silva Telles, Lawyer and Forest Code Expert at Brazil’s Socio-Environmental Institute, points out this is not just public relations: “This does have a chance of passing, and this is serious, ” Silva Telles says.

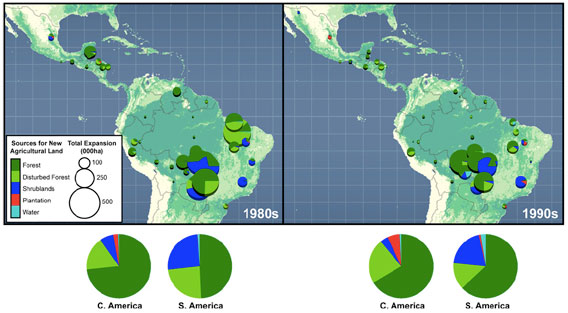

Sources for newly expanded agricultural land in tropical America during the 1980s and 1990s. Caption and image courtesy of Gibbs et al 2010. |

The Forest Code: Reducing Deforestation

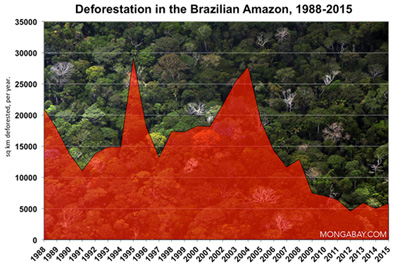

In the last decade, deforestation rates have fallen dramatically in Brazil. From a ten-year high of 2.7 million hectares in 2004, the rate dropped to 0.70 million hectares by 2009.

“Deforestation in Brazil has dropped by two-thirds in the last few years,” explains William Laurence, conservation and tropical biologist at James Cook University in Australia. “We are not sure if this is a permanent reduction, but it is good news.”

Laurence, who worked on the Amazon for fifteen years on behalf of the Smithsonian Institution, points to various factors for this reduction, including improved satellite monitoring and, more significantly, a drop in commodity prices that reduced the incentive to convert forests and other areas of biodiversity into agricultural lands.

But the recent strengthened enforcement of the Forest Code is certainly another factor, according to Laurence. “When commodity prices go back up, there’s concern that deforestation rates will rise too; the strength of the Forest Code will certainly figure in the answer here.”

Raul do Valle Silva Telles also highlights the central role of the Forest Code.

“It is a very modern law,” Telles says. “Since the 1930s, it has told farmers that they have to respect some protected areas inside their own land.” In particular, the Forest Code has provisions for both legal reserves (Reserva Legal (RLs)), which stipulate conservation measures within private property, and protected areas (Área de Preservação Permamente (APPs)), which also directly affect privately owned land and expansion opportunities.

For many years, the Forest Code simply was not respected, according to Telles. In 1988, however, the New Constitution bolstered federal and state environmental agencies, enabling them to put the law in the field—and to give some effectiveness to the law.

The Crux: Recent Changes to the Code

But it is the most recent measures strengthening the Forest Code that have proven to be very effective. And it is these same measures that have galvanized its opponents.

“In 2008,” Valles explains, “new policies were put in place to strengthen the Forest Code. For example, the government limited state bank credits to farmers who didn’t respect the Code in the Amazon. Second, there was a change in a decree and for the first time since 1965, landowners who didn’t have the legal reserve could be fined.”

Valles calls the pressure to reform the Forest Code a predictable conservative backlash to recent enforcement efforts.

What’s in the Package?

The proposed Forest Code reforms would change Brazil’s forest, conservation, and land-use policies in many significant ways. For one thing, there would be a reduction in hectares for mandated legal reserves in privately owned land in the Amazon, Atlantic Forest and Cerrado (mixed-Savanna type) biomes. In addition, larger areas could be designated for small landholdings, which are subject to less stringent conservation requirements.

Under the current Forest Code, APPs include riverbanks, steep slopes and hill tops. The proposed reforms, however, would move APP jurisdiction from the federal to the state level, effectively allowing states to cut them in half.

Other changes include expanded public interest definitions that allow for land utilization; reduced areas of conserved riparian buffer zones; increased states’ prerogatives in protected areas policies; and a retroactive amnesty for deforestation that is linked to eliminating restoration directives.

In the Atlantic Forest, a small landholding with minimal conservation requirements consists of about 30 hectares. Under the proposed reforms, this would be increased to approximately 80 hectares. The legal reserve requirement for forested areas would decline from 80 to 50 percent in the Amazon and from 35 to 20 percent in the Cerrado. Spurred on by these changes, many landowners might also re-demarcate or re-divide their land in order to fall under the small landholder provisions. The amnesty and riparian buffer changes would also have a major impact.

Farmer Amnesty Provisions

“Worst of all, from my point of view, are the amnesty provisions to farmers that haven’t respected the protected areas inside their lands,” Valles says. “Under the current Forest Code, someone that doesn’t have the legal reserve or the fragile areas protected has the obligation to restore them, even if he wasn’t the one who cut the forest—if it was a former owner, for example. In the reform proposal, they can be exempted from this obligation.”

|

To Valles, this is very bad social policy. “First of all, there are huge areas all around the country needing restoration, areas where some environmental services have to be restored,” Valles says. “In the Atlantic Forest, for example, only seven percent of the original forest cover remains, and because of it every year people face floods and landslides in the wet season and water shortage in the dry season. The Forest Code is the only law that could lead to restoration.”

Valles adds that if the amnesty were approved, respect for the law would deteriorate. “Everybody will know that if they broke the law, there will be another amnesty some day forgiving all the irregularities,” he says.

Riverbank Vegetation Conservation

For Laurence, the changes to the riparian provisions are especially ominous for keeping the Amazon biome intact. The proposed reforms would, among other allowances, reduce mandated riverbank vegetation conservation from 30 to 15 meters.

“The riparian provisions of the current Forest Code greatly reduce ecosystem fragmentation—when it is enforced,” Laurence explains. “In the Amazon, you have a complex system of river and streams, and when forest is retained along these, it forms a network of corridors that helps to link forests together and greatly reduces forest fragmentation.”

When forests are fragmented, plant and animal species disappear. “They become locally extinct,” Laurence says, “because the fragment is too small to sustain their populations.”

Laurence also underscores the importance of current riparian criteria that protect against ediment loads falling into streams. In addition, they guard against the destabilization of aquatic oxygen levels that result from excess sunlight falling on waters. This occurs due to the loss of riverside forest cover. This is, as Laurence puts it, a “lethal combination” for the many endemic fish and aquatic species in the Amazon that need cool, highly oxygenated water.

“There are lots of reasons to favor riparian protection,” Laurence says.

Domestic and International Leadership

Both Brazilians and non-Brazilians also feel that the proposed changes would undercut the nation’s constructive leadership in climate change talks, especially among tropical and heavily forested nations.

Prior to the December 2009 Copenhagen UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), President Lula declared that Brazil would aim for a greenhouse gas emissions reduction just shy of 40 percent from expected 2020 levels. Shortly after the negotiations were completed on December 29, 2009, the goal became policy, with Lula signing into law Brazil’s goal of reducing emissions by 36 to 39 percent of expected 2020 levels.

“The proposed reforms would have great bearing on Brazil’s international stature,”

Valles says. “In Copenhagen, Brazil presented its national policy on climate change. It was one of the best things to come out of Copenhagen. Now, 80 percent of our goal for reducing emissions is from avoided deforestation. If this reform is passed, we have no chance to meet the goal. If the reform is passed, deforestation will not decrease.”

The next UNFCCC talks will take place in Cancun, Mexico, at the end of 2010. Before that, however, the Convention on Biological Diversity will hold its 10th Conference of the Parties in Nagoya, Japan in October. Some are hoping that the Nagoya Conference will be the site of a major declaration by Brazil on reducing deforestation. Moreover, the buzz building around the 2012 Rio + 10 Conference in Rio de Janeiro is just one more example of how the rest of the world is looking to Brazil for leadership on the greatest sustainable development challenge of this generation.

The proposed reforms to the Forest Code have created a certain uneasiness. They have also raised questions as to how commitments, responses and common positions will be forged in the next two years.

Change – But Which Change?

Valles does see a need for Forest Code reform, but not the type currently proposed by Rebelo and his partners.

“We know we have to have some changes in the policy,” Valles explains. “The law did not have enough enforcement. We know more than 70 to 80 percent of farmers have some problems with the Forest Code. We need other tools, economic tools, and other supportive policies, such as ecosystem service payments.”

Offering an example of what should change, Valles says, “More than 50 percent of the credit that goes to agriculture is from state banks, from public money. We should have a distinction in the credit policies for those who respect the Forest Code and those who don’t.”

Others who are concerned over the proposed changes to the Forest Code also express the desire for new policies that promote prosperous agriculture as well as effective

conservation. Addressing this, the Brazilian scientists who wrote to Science asked, “Is it possible to combine modern tropical agriculture with environmental conservation? Brazilian agriculture offers encouraging examples that achieve high production together with adequate environmental protection.”

In a similar vein, Bill Laurence points to the possibility of moving away from an expansion model that is marked by cheap land prices and inefficiency to more intensive and higher yielding practices on land that has already been cleared. In the Amazon, farmers often burn and clear forests for inefficient livestock farming. Tree plantations and fruit crops are two good examples of how farmers can “invest in more intensive and sustainable types of farming,” Laurence says.

If both sustainable farming and forest conservation manage to not only coexist but thrive, the next slogan to hit the rainforest might just be “Farms and Forests Here.”

Richard Blaustein is a free-lance journalist based in Washington, DC.

Chris Santiago is a freelance writer and editor who frequently blogs for Change.org. He most recently worked at McGraw-Hill and “got green” at Oberlin College.

Related articles

Controversial changes to Brazilian forest law passes first barrier

(07/08/2010) An amendment to undermine protections in Brazil’s 1965 forestry code has passed it first legislative barrier, reports the World Wide Fund for Nature-Brasil (WWF). Yesterday the amendment passed a special vote in the Congress’s Special Committee on Forest Law Changes.

Amazon and Atlantic Forest under threat: politicians press to dilute Brazil’s forestry law

(07/01/2010) A group of Brazilian legislatures, known as the ‘ruralistas’, are working to change important aspects of the Brazil’s landmark 1965 forestry code, undermining forest protection in the Amazon and the Mata Atlantica (also known as the Atlantic Forest) and perhaps heralding a new era of booming deforestation. The ruralistas, linked to big agribusiness and landowners, are taking aim at the part of the forestry code that requires landowners in the Amazon to retain 80 percent of their land area as legal reserves, arguing that the law threatens agricultural development.

Ending deforestation could boost Brazilian agriculture

(06/26/2010) Ending Amazon deforestation could boost the fortunes of the Brazilian agricultural sector by $145-306 billion, estimates a new analysis issued by Avoided Deforestation Partners, a group pushing for U.S. climate legislation that includes a strong role for forest conservation. The analysis, which follows on the heels of a report that forecast large gains for U.S. farmers from progress in gradually stopping overseas deforestation by 2030, estimates that existing Brazilian farmers could see around $100 billion from higher commodity prices and improved access to markets. Meanwhile landholders in the Brazilian Amazon—including ranchers and farmers—could see $50-202 billion from carbon payments for forest protection.

(06/24/2010) Not surprisingly, a US report released last week which argued that saving forests abroad will help US agricultural producers by reducing international competition has raised hackles in tropical forest counties. The report, commissioned by Avoided Deforestation Partners, a US group pushing for including tropical forest conservation in US climate policy, and the National Farmers Union, a lobbying firm, has threatened to erode support for stopping deforestation in places like Brazil. However, two rebuttals have been issued, one from international environmental organizations and the other from Brazilian NGOs, that counter findings in the US report and urge unity in stopping deforestation, not for the economic betterment of US producers, but for everyone.

How to save the Amazon rainforest

(01/04/2009) Environmentalists have long voiced concern over the vanishing Amazon rainforest, but they haven’t been particularly effective at slowing forest loss. In fact, despite the hundreds of millions of dollars in donor funds that have flowed into the region since 2000 and the establishment of more than 100 million hectares of protected areas since 2002, average annual deforestation rates have increased since the 1990s, peaking at 73,785 square kilometers (28,488 square miles) of forest loss between 2002 and 2004. With land prices fast appreciating, cattle ranching and industrial soy farms expanding, and billions of dollars’ worth of new infrastructure projects in the works, development pressure on the Amazon is expected to accelerate. Given these trends, it is apparent that conservation efforts alone will not determine the fate of the Amazon or other rainforests. Some argue that market measures, which value forests for the ecosystem services they provide as well as reward developers for environmental performance, will be the key to saving the Amazon from large-scale destruction. In the end it may be the very markets currently driving deforestation that save forests.

Future threats to the Amazon rainforest

(07/31/2008) Between June 2000 and June 2008, more than 150,000 square kilometers of rainforest were cleared in the Brazilian Amazon. While deforestation rates have slowed since 2004, forest loss is expected to continue for the foreseeable future. This is a look at past, current and potential future drivers of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon.