The decision last week by the Brazilian government to move forward on the $17 billion Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu river will set in motion a plan to build more than 100 dams across the Amazon basin, potentially turning tributaries of the world’s largest river into ‘an endless series of stagnant reservoirs’, says a new short film released by Amazon Watch and International Rivers.

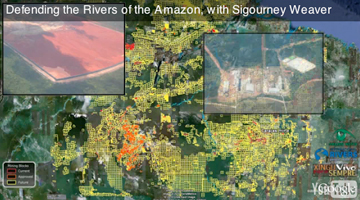

The film, narrated by Sigourney Weaver, uses a Google Earth 3-D tour to illustrate the potential impact of the dam. Belo Monte’s reservoirs will flood 668 square kilometers, including parts of the city of Altamira, displacing more than 20,000 people. It will reduce the flow of the mighty Xingu to a trickle during parts of the year, reducing water supplies for downstream indigenous populations, blocking fish migration thereby disrupting local fisheries, and likely condemning several aquatic species to extinction. Flooding of forest areas will generate massive amounts of methane, a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent that CO2, and increase the risk of malaria in surrounding areas. Furthermore, if earlier dam projects in the Amazon are any model, Belo Monte will contribute to large-scale deforestation by local people who can no longer earn income from fishing or traditional livelihoods. Electricity grids, transmission lines, and access roads will put further pressure on the rainforest.

|

The Belo Monte Dam would be “a disaster for the Xingu River, for the rainforest, and certainly for all the indigenous people and families living along the river,” said Weaver, an actress who starred in last year’s blockbuster Avatar. “Their way of life will disappear.”

Belo Monte has faced fierce opposition from indigenous people, activists, and even celebrities like Weaver and James Cameron, the director of Avatar, Titanic, and the Terminator series of movies. But the project is backed by powerful interests, including the mining sector: Belo Monte is being built to supply electricity for new mines in the Amazon. The video includes a “flyover” via Google Earth showing the nearby Carajas mine, one of the largest iron ore mines on the planet.

The 10-minute video, created by Amazon Watch and International Rivers with technical assistance from Google Earth Outreach, comes as part of the Altamira-based Movimento Xingu Vivo Para Sempre (Xingu River Forever Alive Movement) campaign against the dam.

Antonia Melo, a leader and spokesperson of the Xingu River Forever Alive Movement, said the video will help people better understand the impacts of the project.

“Even for people who live along the Xingu River itself, the impacts of damming the river are difficult to understand. This animation can help the local population visualize the potential damage caused by Belo Monte, and can encourage them to take action,” Melo said in a statement.

|

Rebecca Moore of Google Earth Outreach said she hoped the video would lead to more engagement on the issue.

“Because Google Earth provides such a realistic model of the real earth, it can allow both ordinary people and decision makers to visualize and understand complex environmental and social issues more easily and deeply,” she said in a statement. “Ideally, this can lead to a more informed and constructive dialogue, especially for controversial issues such as the Belo Monte Dam.”

A Google Earth version of the video can be downloaded at Belo Monte Tour.

Belo Monte is among the most controversial of some 146 major dams planned in the Amazon basin over the next two to three decades. Earlier this month International Rivers launched a new website, Dams in Amazonia, outlining the sites and impacts of these dams with an interactive map.

|

Related articles

146 dams threaten Amazon basin

(08/19/2010) Although developers and government often tout dams as environmentally-friendly energy sources, this is not always the case. Dams impact river flows, changing ecosystems indefinitely; they may flood large areas forcing people and wildlife to move; and in the tropics they can also become massive source of greenhouse gases due to emissions of methane. Despite these concerns, the Amazon basin—the world’s largest tropical rainforest—is being seen as prime development for hydropower projects. Currently five nations—Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru—are planning over 146 big dams in the Amazon Basin. Some of these dams would flood pristine rainforests, others threaten indigenous people, and all would change the Amazonian ecosystem. Now a new website, Dams in Amazonia, outlines the sites and impacts of these dams with an interactive map.

Indigenous tribes occupy dam in Brazil, demand reparations

(07/27/2010) An indigenous group in Brazil has taken over a hydroelectric dam, which they state has polluted vital fishing grounds and destroyed sacred burial ground. They are demanding reparations for the damage done and that no more dams are built in the region without their prior consent.

Environmentalists and indigenous groups condemn plan for six dams in Peruvian Amazon

(06/21/2010) Environmentalists and indigenous groups have come together to condemn a 15 million US dollar plan for six hydroelectric dams in the Peruvian Amazon, signed last week by Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Peruvian President, Alan Garcia. While the six dams would produce over 6,000 megawatts, mostly for Brazil, critics say the dams will flood tens of thousands of hectares of rainforest, devastate the lifestyles of a number of indigenous groups, and only serve big Brazilian corporations.

‘Prepare for war’: tensions rising over Brazil’s controversial Belo Monte dam

(05/25/2010) Tensions are flaring after Brazil’s approval of the Belo Monte dam project last month to divert the flow of the Xingu River. The dam, which will be the world’s third larges, will flood 500 square miles of rainforest, lead to the removal of at least 12,000 people in the region, and upturn the lives of 45,000 indigenous people who depend on the Xingu. After fighting the construction of the dam for nearly thirty years, indigenous groups are beginning to talk of a last stand.

(04/01/2010) After creating a hugely successful science-fiction film about a mega-corporation destroying the indigenous culture of another planet, James Cameron has become a surprisingly noteworthy voice on environmental issues, especially those dealing with the very non-fantastical situation of indigenous cultures fighting exploitation. This week Cameron traveled to Brazil for a three-day visit to the Big Bend (Volta Grande) region of the Xingu River to see the people and rainforests that would be affected by the construction of the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Dam. Long-condemned by environmentalists and indigenous-rights groups, the dam would destroy 500 square kilometers of pristine rainforest and force the relocation of some 12,000 people.

Google’s Earth Engine to help tropical countries monitor forests

(12/16/2009) A powerful forest monitoring application unveiled last week by Google will be made freely available to developing countries as a means to build the capacity to quality for compensation under REDD, a proposed climate change mitigation mechanism that would pay tropical countries for protecting forests, according to a senior Google engineer presenting at a side event at COP15 in Copenhagen.

How satellites are used in conservation

(04/13/2009) In October 2008 scientists with the Royal Botanical Garden at Kew discovered a host of previously unknown species in a remote highland forest in Mozambique. The find was no accident: three years earlier, conservationist Julian Bayliss identified the site—Mount Mabu—using Google Earth, a tool that’s rapidly becoming a critical part of conservation efforts around the world. As the discovery in Mozambique suggests, remote sensing is being used for a bewildering array of applications, from monitoring sea ice to detecting deforestation to tracking wildlife. The number of uses grows as the technology matures and becomes more widely available. Google Earth may represent a critical point, bringing the power of remote sensing to the masses and allowing anyone with an Internet connection to attach data to a geographic representation of Earth.

Development of Google Earth a watershed moment for the environment

(03/31/2009) Satellites have long been used to detect and monitor environmental change, but capabilities have vastly improved since the early 1970s when Landsat images were first revealed to the public. Today Google Earth has democratized the availability of satellite imagery, putting high resolution images of the planet within reach of anyone with access to the Internet. In the process, Google Earth has emerged as potent tool for conservation, allowing scientists, activists, and even the general public to create compelling presentations that reach and engage the masses. One of the more prolific developers of Google Earth conservation applications is David Tryse. Neither a scientist nor a formal conservationist, Tryse’s concern for the welfare of the planet led him develop a KML for the Zoological Society of London’s EDGE of Existence program, an initiative to promote awareness of and generating conservation funding for 100 of the world’s rarest species. The KML allows people to surf the planet to see photos of endangered species, information about their habitat, and the threats they face. Tryse has since developed a deforestation tracking application, a KML that highlights hydroelectric threats to Borneo’s rivers, and oil spills and is working on a new tool that will make it even easier for people to create visualizations on Google Earth. Tryse believes the development of Google Earth is a watershed moment for conservation and the environmental movement.

Photos: Google Earth used to find new species

(12/22/2008) Scientists have used Google Earth to find a previously unknown trove of biological diversity in Mozambique, reports the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew. Scouring satellite images via Google Earth for potential conservation sites at elevations of 1600 meters or more, Julian Bayliss a locally-based conservationist, in 2005 spotted a 7,000-hectare tract of forest on Mount Mabu. The scientifically unexplored forest had previously only been known to villagers. Subsequent expeditions in October and November this year turned up hundreds of species of plants and animals, including some that are new to science.