As climate change negotiations continue full force in the Danish city of Copenhagen, Latin American countries are hoping the Global North will commit to its “climate debt” by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and providing resources to poor nations. It’s certainly an understandable aspiration: Latin America only produces five per cent of global emissions of carbon dioxide, a chief greenhouse gas, yet the region has borne the brunt of extreme weather ranging from droughts to flooding.

One key figure pressuring the Global North to live up to its responsibilities is Rafael Correa, firebrand president of the small Andean nation of Ecuador. A popular leader recently elected to a second presidential term, Correa has allied himself to Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez and the so-called leftist “Pink Tide” sweeping through South America. He’s the first leftist to win the presidency in Ecuador since the country returned to civilian rule in 1979. Indignantly, Correa blames rich nations for disastrous floods which destroyed hundreds of millions of dollars worth of crops in his country last year.

Oil pipeline in the Amazon rainforest of Ecuador |

While it’s still unclear whether Correa will put in a personal appearance in Copenhagen, Ecuadoran officials will certainly be raising an issue of key importance to their countrymen: the fate of the Amazon jungle. While the largest swathe of the Amazon lies in Brazil, Ecuador also has its share of rainforest in the so-called Oriente region.

Unfortunately however, U.S. oil company Texaco despoiled the Oriente over the course of many years which resulted in an environmental and public health emergency for local indigenous peoples in the area [to learn more about Texaco’s black history in Ecuador, read my recent online review of the documentary film Crude].

To his credit, Correa has voiced support for Indians who have launched an environmental lawsuit against Texaco — now Chevron. Ambitiously however the combative Ecuadoran president has gone yet further in pushing for environmental protection in the Amazon. Under his Yasuní-ITT initiative, Ecuador would forgo oil exploitation in an Amazon nature reserve in exchange for billions of dollars in aid from wealthy nations.

Located in the Ecuadoran Amazon, Yasuní national park is home to the largest number of tree species per hectare on the planet and also contains endangered monkeys, pumas and jaguars. The Ecuadoran government has stated that it would not extract oil within the so-called Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini (or ITT) oil fields located in Yasuní if the Global North provided the Andean nation with necessary funding.

In addition to rare animals Yasuní is home to the Taromenane, one of the world’s last uncontacted indigenous tribes. As oil presence has grown in the vicinity these hunter gatherers have come under threat: in 2003 unknown assailants killed 26 Taromenane in an ambush. The Indians have hit back and are thought to be the authors of a recent spear attack upon a settler family. One victim of the attack, a 12-year old girl, told oil workers shortly before she died that her attackers were almost entirely naked.

Not only would Correa’s ingenious plan take pressure off the Taromenane but also help to ameliorate climate change. Indeed, the President says that if Ecuador were to avoid burning Yasuní oil — and logging the rainforest to get it — the world might avoid the creation of 547 million tons of carbon dioxide going into the atmosphere. It’s a fabulous idea and best of all the Correa government would use proceeds from the ITT-Yasuní trust to prevent further deforestation.

For a country like Ecuador, getting at Yasuní’s oil is a tempting target: currently the Andean nation derives a whopping 35% of its public spending budget from petroleum exports. Correa could well use the added money: currently half the Ecuadoran population lives in poverty.

|

Related articles

Will Ecuador’s plan to raise money for not drilling oil in the Amazon succeed? (10/27/2009) Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park is full of wealth: it is one of the richest places on earth in terms of biodiversity; it is home to the indigenous Waorani people, as well as several uncontacted tribes; and the park’s forest and soil provides a massive carbon sink. However, Yasuni National Park also sits on wealth of a different kind: one billion barrels of oil remain locked under the pristine rainforest. Oil road transforms indigenous nomadic hunters into commercial poachers in the Ecuadorian Amazon (09/13/2009) The documentary Crude opened this weekend in New York, while the film shows the direct impact of the oil industry on indigenous groups a new study proves that the presence of oil companies can have subtler, but still major impacts, on indigenous groups and the ecosystems in which they live. In Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park—comprising 982,000 hectares of what the researchers call “one of the most species diverse forests in the world”—the presence of an oil company has disrupted the lives of the Waorani and the Kichwa peoples, and the rich abundance of wildlife living within the forest. Amazon tribes have long fought bloody battles against big oil in Ecuador (09/03/2009) The promotional efforts ahead of the upcoming release of the film Crude have helped raise awareness of the plight of thousands of Ecuadorians who have suffered from environmental damages wrought by oil companies. But while Crude focuses on the relatively recent history of oil development in the Ecuadorean Amazon (specifically the fallout from Texaco’s operations during 1968-1992), conflict between oil companies and indigenous forest dwellers dates back to the 1940s. |

But Correa, who issued lime-green posters emblazoned with the slogan “citizen revolution” during his first run for the presidency, and who has renamed the oil ministry the “ministry of non-renewable resources,” is busily pitching ITT-Yasuní to European governments instead of moving ahead with sensitive oil exploration. In exchange for preserving Yasuní, Correa wants $350 million a year from the Global North for the next ten years.

In the run-up to the climate conference in Copenhagen, Correa and Ecuadoran officials have been circling the globe to attract support for ITT-Yasuní. So far Spain, France and Italy have expressed interest in canceling Ecuador’s debts. But when Correa sought to set up a meeting with British MP’s about Yasuní-ITT, he was rebuffed and told that parliamentarians were too busy with other matters. To date, only Germany has agreed to pay Ecuador $50 million annually for 13 years.

Inaction in the Global North has allowed Correa to take the moral high ground. In London he declared that rich countries were primarily responsible for climate change and it was they who should pay Ecuador not to release carbon into the atmosphere as “compensation for the damages caused by the out-of-proportion amount of historical and current emissions of greenhouse gases.” But while Correa’s fiery denunciations are certainly on target it would be a mistake to view the controversy over Amazonian resources as a simple struggle between the Ecuadoran government and wealthier, more polluting countries.

According to Alberto Acosta, Ecuador’s former Minister of Energy and Mines, the President has been an ambivalent environmentalist. An economist, Acosta left his post due to disagreements with other government officials about oil development in Yasuní. When I was in Quito doing research for my book Revolution! South America and the Rise of the New Left (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2008), I spoke with Acosta and he struck me as a dynamic and principled man. During our discussion he animatedly quoted Bertolt Brecht at length on the need for greater citizen engagement in politics.

In an interesting interview posted on the website Rebelión Acosta remarked that it was civil society and not Rafael Correa which originally pushed the ITT-Yasuní idea. For years, he says, Indians who witnessed the destruction wreaked by Texaco had called for a moratorium on oil exploration in the Amazon. Indigenous peoples were joined by a group of dedicated activists working with a non-governmental organization (or NGO) called Acción Ecológica.

When I was in Ecuador in the 1990s researching some stories about oil exploration in the Amazon I recall interviewing environmentalists working with Acción Ecológica including an insightful woman named Esperanza Martínez. Even before Acosta arrived in his post, Martínez pushed hard for ITT-Yasuní and held discussions with the economist. Later, Acosta took up the idea of ITT-Yasuní with other government officials, a development which provoked a “confrontation” within the Correa regime.

Acosta’s colleagues could not understand why the Minister of Energy and Mines no less would want to keep Amazonian oil in the ground. In particular, Acosta encountered resistance from the state oil company Petroecuador which sought to actually accelerate petroleum development in the rainforest. In addition to serving as minister, Acosta was president of Petroecuador’s board of directors during this time. However, little did Acosta know that behind his back the company’s executive president was seeking to seal deals with the Brazilian and Venezuelan state energy companies amongst others in an effort to move forward with controversial oil exploration.

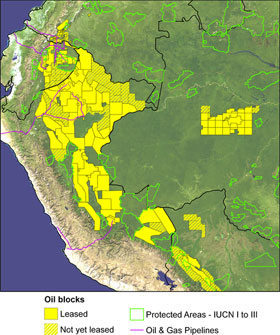

Oil and gas blocks in the western Amazon. Solid yellow indicates blocks already leased out to companies. Hashed yellow indicates proposed blocks or blocks still in the negotiation phase. Protected areas shown are those considered strictly protected by the IUCN (categories I to III). Image courtesy of PLoS ONE |

At one tense Petroecuador board meeting, Correa himself showed up and heard the arguments both for and against oil exploration in the Amazon. At long last, the president agreed to leave the oil in the ground as long as Ecuador could acquire some sort of international financial compensation. Today in Copenhagen Ecuador is proud of its ITT-Yasuní plan but according to Acosta the president has been a reluctant environmentalist, at times raising objections to the scheme and at others moving to slow down momentum and crucial progress.

More significantly, in early 2009 the Ecuadoran authorities moved to shut down Acción Ecológíca — the very same organization which had proven so crucial in pushing the ITT-Yasuní proposal in the first place. Claiming that the group had “not complied with the aims for which it [the NGO] was created,” the government withdrew Acción Ecológíca’s legal charter. Speaking to the Ecuadoran media, Esperanza Martínez expressed shock and dismay at the move. The Correa government, she declared, was simply trying to silence its environmental critics.

The government vehemently denied the charges but in light of the timing it’s possible the environmentalists were correct in their suspicions. Indeed, the government acted to shut down Acción Ecológica shortly after the NGO called for sanctions against a consortium operating an environmentally problematic oil pipeline.

For a year before that Acción Ecológica had furthermore opposed Correa’s new mining law which in the NGO’s view solely benefited transnational mining companies at the expense of local communities. Though the authorities later moved to reestablish Acción Ecológica’s legal status, the heavy handed government decision came as a shock to some foreign and progressive Ecuadorans who had otherwise been heartened by Correa’s ecologically friendly proposals like ITT-Yasuní.

If the Accíon Ecológica affair was not enough of a big, black blot on Correa’s environmental record consider the president’s retrograde attitude towards natural resources. Though Indians backed Correa’s initial election they later grew leery of the government when authorities pushed for a new law regulating water. The proposed law, they said, would lead to an eventual privatization of water resources. Concerned about mining and water, and apprehensive about oil development proceeding on their lands, Indians recently protested the Correa regime by blocking Amazonian roads.

Condescendingly, Correa called Indians “infantile” for objecting to legislation which would deny them consultation on mining and oil drilling projects. “We do not accept that a government that says it is in favor of marginalized people should not take their views into account when it makes laws,” countered indigenous leader Humberto Cholango. “It’s inconceivable that laws as important as those on mining…should be passed without public debate, or that they should contain articles that run counter to the constitution itself, which enshrines the rights of nature,” he added.

Tragically, protests along the blocked roads led to violence. The Indians claimed that 500 police attacked them which resulted in two deaths and nine wounded by gunshots. The Correa government, the Indians declared, had “blood on its hands” and pledged to carry out international legal action over violations of their collective and human rights. The government denies the police ever fired their guns and reports that some security forces were also wounded in the battle.

In the short run the Indians may have won this round against the Correa government: in the wake of the battle the President sat down with indigenous leaders in Quito and agreed to reconsider mining and water laws. In the long term however Correa must take on the mounting political contradictions which characterize his regime.

Even as he rails against the Global North for causing climate change and seeks to secure vital funding to save Yasuní, Correa seems unable or unwilling to make a fundamental break with the age old extractive economy. For their part, the Indians believe they don’t have enough control over their ancestral lands and natural resources.

How can Ecuador get out of this polarized and vicious cycle? Early on during his first administration, Correa visited the ugly Amazonian oil boom town of Coca and remarked “I think oil has brought us more bad than good. We need to do something about it.” Despite his rhetoric however Correa has not done enough to put tiny Ecuador on an alternative path. Yet economist Acosta argues that Ecuador must try to create a “post-petroleum” economy. “Extracting natural resources doesn’t develop us,” he says.

Nikolas Kozloff is the author of the forthcoming No Rain in the Amazon: How South America’s Climate Change Affects the Entire Planet (Palgrave Macmillan, April 2010). Visit his website, senorchichero.