The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the largest private funder of Amazon rainforest conservation, is playing an unheralded but integral role in the development of the Earth Engine platform, a system that combines the computing power of Google with advanced monitoring and analysis technologies developed by leading environmental scientists. The platform, which was officially unveiled at climate talks in in Copenhagen, promises to enable near real-time monitoring of the world’s forests and carbon at high resolution at selected sites before COP-16 in Mexico.

This CLASlite image of the Amazon Basin shows deforested regions in pink and blue, and intact forests in green. |

The Earth Engine builds upon decades of research by scientists at a range of institutions, including NASA, the Woods Hole Research Center, Brazil’s Imazon, and the Carnegie Institute. While it is so far only available for the Amazon and the Andes region in South America, the model is highly scalable and could eventually be applied virtually anywhere on Earth, enabling three-dimensional mapping of ecosystems and rapid reporting of land cover change, including alerting of deforestation and incidence of fire. The tool could play a critical role in helping countries win compensation under REDD, a mechanism that rewards countries for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. REDD is seen by many as perhaps the best way to generate funds for protection and sustainable use of forests.

In an interview with mongabay.com, Dr. Luis Solórzano, Director of the Environmental Science Program at the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, discussed the development of the Earth Engine as well as the Moore Foundation’s broader support of Amazon conservation initiatives.

AN INTERVIEW WITH DR. LUIS SOLORZANO

Mongabay: The Moore Foundation is the largest single private funder of Amazon conservation and research initiatives since 2000, and perhaps in history. What is the foundation’s objective?

Luis Solórzano: The goal of the Moore Foundation’s Environmental Conservation Program is to change the ways in which people use important terrestrial and coastal marine ecosystems to conserve critical ecological systems and functions, while allowing sustainable use. In order to achieve that overarching goal, we ought not only to set aside ecologically important terrestrial and coastal marine ecosystems but also transform the ways in which we perceive and interact with them today.

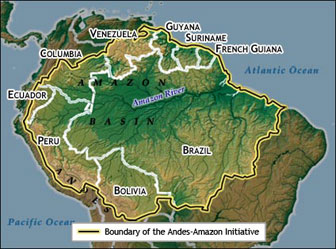

Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s Andes-Amazon Initiative |

The goal for the Andes Amazon Initiative (AAI) is to maintain the hydrological and climatic function of the basin as well as its representative biodiversity –you can’t have one without the other.

For the first 7 years the AAI has focused much of its strategy on helping governments and civil society place forested lands under protection (i.e., creating protected areas). The objective has been to contribute to the long-term preservation of the ecological functions (climate and hydrology) and evolutionary process (e.g., dispersal, adaptation, etc) necessary to maintain the remarkable biodiversity found across the basin.

Mongabay: The Moore Foundation is working with a number of innovative organizations ranging from projects run by indigenous groups to community-based programs to the Brazilian government to NASA. How does the foundation select its partners?

|

Ethnographic maps built using cutting-edge technology may help Amazon tribes win forest carbon payments

(11/29/2009) A new handbook lays out the methodology for cultural mapping, providing indigenous groups with a powerful tool for defending their land and culture, while enabling them to benefit from some 21st century advancements. Cultural mapping may also facilitate indigenous efforts to win recognition and compensation under a proposed scheme to mitigate climate change through forest conservation. The scheme—known as REDD for reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation—will be a central topic of discussion at next month’s climate talks in Copenhagen, but concerns remain that it could fail to deliver benefits to forest dwellers. |

Luis Solórzano: The GBMF is organized by programs with initiatives within each program. Initiatives are major efforts to effect large-scale, long-term change.

Our initiative teams develop plans that explain the context and baseline conditions of the “conservation target” and then propose comprehensive solutions that are articulated in a theory of change (TOC). The TOC is a coherent explanation of a set of strategies, tactics and interrelated interventions most likely to cause positive change against the baseline conditions of the conservation target – we basically take a systems-based approach. Strategic planning results in roadmaps that identify the set of prioritized interventions (grants, convening, facilitating, etc.) for the greatest impact. This process is iterative – and internally reviewed every year – to make sure we incorporate contextual changes and manage our interventions adaptively.

In our grantmaking, we scan the stakeholder landscape, searching for potential collaborators whose work aligns with the Initiative’s goals and strategies. As a result, we don’t accept unsolicited proposals, and when we engage with grantees, we build grant plans in a collaborative way.

Mongabay: The Moore Foundation has done a lot of work building capacity to support ecosystem services payments systems like the REDD mechanism?

Luis Solórzano: Evidence has shown us that a protected area-based approach to large-scale conservation does not, by itself, yield the greatest results for conserving critical ecological systems and functions across the Andes Amazon landscapes.

To achieve a deep and transformative change to the current trajectory of ecosystems’ degradation and losses, we require additional, novel approaches and mechanisms. REDD has been one of those emerging opportunities and we have been actively supporting REDD-related activities since last year.

Mongabay: As part of the effort to track deforestation, the Moore Foundation has coordinated an ambitious satellite monitoring system involving cutting-edge technology and multiple partners. Can you tell us a little about this project and how it could help boost efforts to protect the environment?

Luis Solórzano: Yes, for the last 3 years we have partnered with Google.org and the Google Earth team in an effort to enable global, accessible and transparent capability to monitor forests: the “Earth Engine” platform. Our partnership builds primarily on a shared belief that by making use of the best science and technology tools, society can turn the tide of human induced destruction of our planet’s life support systems toward sustainable use. We have been collaborating with scientists, private sector, governments and philanthropies—all motivated and united by our collective commitment to halt some of the most severe threats to our global environment.

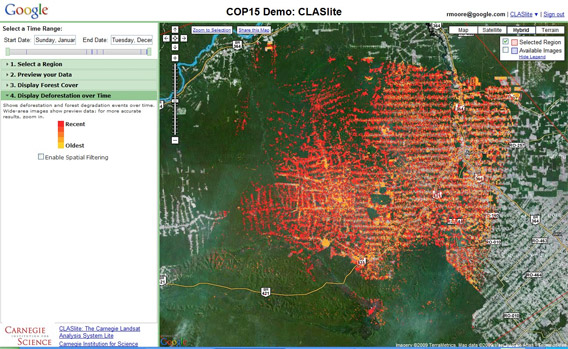

Google Earth to monitor deforestation |

Our short term goal was to create the enabling conditions to deploy an accessible web-based platform, capable of distributing massive amounts of critical data and information, together with the capacity to employ state-of-the-art analysis tools that will enable the global community to monitor transparently and improve the way in which we manage the Earth’s environment.

An important milestone has just been achieved and announced this week in Copenhagen. The new prototype system enables forest monitoring by an indigenous group in the Amazon, a small or large NGO, or a municipality, state, or national government.

This platform has built on decades of previous scientific research by Dr Greg Asner at the Carnegie Institute, Dr Carlos Souza at Imazon, and Dr Josef Kellndorfer at the Woods Hole Research Center, and it is now supported by some of Google’s best engineering, scientific talent – Noel Gorelick and Matt Hanker are scientists who went to Google after working for NASA – and computing power.

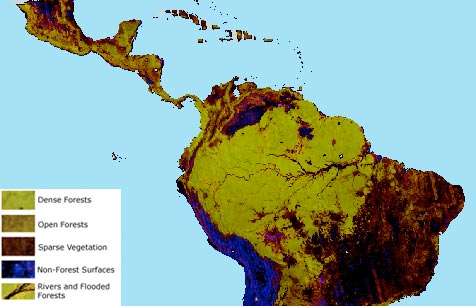

The Woods Hole Research Institute is working to classify the pan-tropical ALOS image mosaic

data into forest cover information.

We first co-funded Josef Kellndorfer (together with Google and the Packard Foundation) at the Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC) to produce spatially consistent pan-tropical data sets to help monitor forest cover and associated carbon stocks stored in above-ground forest biomass. WHRC has been working with products from the Japanese ALOS satellite, LANDSAT and MODIS; this was also achieved thanks to the generosity of the Japanese Space Agency Ajax and NASA which donated their data. This project has already made important progress processing the ALOS data for all the tropical forest of the planet. WHRC has also initiated the training of technical technicians from governments in Latin America and some African and South East Asia countries. The capacity building work will continue over the next years by training technicians in Woods Hole, and carrying out collaborative fieldwork in several selected countries. The goal is to make sure that the technical capacity will be built and remains in the countries after our funding and activities are completed –that’s when we will be done.

CLASlite online: This shows deforestation and degradation in Rondonia, Brazil

from 1986-2008, with the red indicating recent activity.

We have also supported Greg Asner at the Carnegie Institution for Science to transform CLASS, a very sophisticated image analysis software that required substantial computing power, into “CLASlite”, a simpler to use tool that operates in a modern laptop. This software has now been incorporated in the Earth Engine prototype that enables online, global-scale observation and measurement of changes in the Earth’s forests. Since the beginning of this year the Carnegie Institute has been advancing capacity building work across six eight Andes Amazon region countries. As part of that capacity building work technical staff from government and local NGOs and universities have already been trained in the use of the CLASlite desktop version. A similar process occurred with Carlos Souza’s Sistema de Alerta de Deforestation (SAD) to analyze forest cover change.

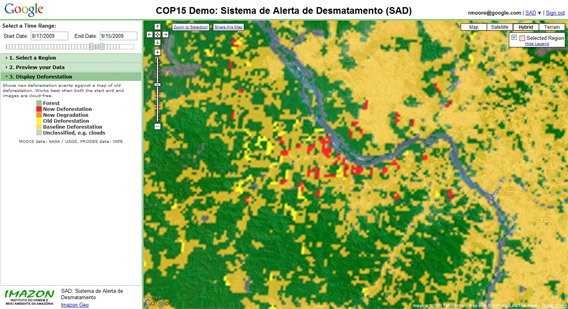

SAD online: The red “hotspots” indicate deforestation that has happened within the last 30 days. The result of running SAD in a region of recent deforestation pressure in Mato Grosso, Brazil.

>BR?

Mongabay: The Moore Foundation has embraced technology as a means to leverage efforts to protect the Amazon on a basin-wide scale. Is the hope that these technologies will be scalable to the entire planet?

Luis Solórzano: Yes, “scalable” is precisely the key notion and our goal in partnership with a group of committed scientists and Google. The Earth Engine platform is fully scalable to the globe and capable of distributing massive amounts of critical data and information, together with the computing power to make use of innovative scientific analysis tools like those developed by Carnegie and Imazon.

At the Copenhagen Climate Conference COP-15, during a Avoided Deforestation Partners high level event, on December 16 Brian McClendon – Vice President, Google, Inc., and Co-Founder, Google Earth announced the launching of “Earth Engine” and U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack a $1 billion U.S. contribution to forest conservation. Right to Left: Jane Goodall, DBE, Founder – The Jane Goodall Institute and UN Messenger of Peace; Brian McClendon – Vice President, Google, Inc., and Co-Founder, Google Earth; Hon. Eduardo Braga, – Governor, Amazonas, Brazil; Julia Marton-Lefèvre – Director General, IUCN; Mark Tercek – President and CEO,The Nature Conservancy; Frances Beinecke – President, National Resources Defense Council; Carter Roberts – President,World Wildlife Fund, U.S. Peter Seligmann – Chairman and CEO, Conservation International; and U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack |

We recognize that science and technology solutions cannot solve our global environmental challenges alone. Instead, a fundamental element of our vision is that the Earth Engine platform will open spaces for the collaborative, resourceful creation of knowledge, and that it will be driven by the particular demands of communities, governments, and civil society.

We see tremendous potential for delivering significant and transformative results to help overcome our current global environmental predicament. We will only succeed as the dynamic creativity, resourcefulness, and diverse views of multiple stakeholders, come together to “own” the Earth Engine platform and use it to craft solutions.

Information technology can be a vehicle for bringing global society — empowered by broad and transparent access to the best available science and technological capacity — together.

Mongabay:

Despite its monumental contributions to conservation, the Moore Foundation has largely stayed out of the limelight. Is there a reason for this humility?

It is part of our culture, and it derives from the vision and values of our founders, Gordon and Betty Moore. As they have said, and as we believe, the credit belongs to our grantees.

Luis Solórzano: It is part of our culture, and it derives from the vision and values of our founders, Gordon and Betty Moore. As they have said, and as we believe, the credit belongs to our grantees.