As hunting wolves is legal again in two American states, Montana and Idaho, researchers have discovered an important role these large predators play in creating nutrient hotspots in forest environments.

Researchers from Michigan Technological University found that when wolves take down their prey—in this case moose—they do more than simply keep a check on herbivore populations. The corpses of wolf-hunted moose create hotspots of forest fertility by enriching the soil with biochemicals. Due to this sudden up-tick in nutrients, microbial and fungal growth explodes, in turn providing extra nutrients for plants near the kill.

“This study demonstrates an unforeseen link between the hunting behavior of a top predator—the wolf—and biochemical hot spots on the landscape,” said Joseph Bump, an assistant professor in Michigan Tech’s School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science and first author of the research paper. “It’s important because it illuminates another contribution large predators make to the ecosystem they live in and illustrates what can be protected or lost when predators are preserved or exterminated.”

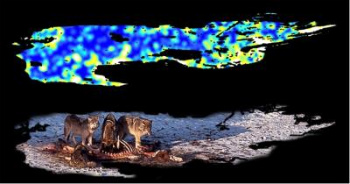

The coastline of Isle Royale National Park is represented in two maps. Moose carcasses, like the ones on which wolves are feeding in lower map, produce pulses of nutrients that affect soil fertility, decomposition and the nutrition of nearby plants. Clustered hotspots of biogeochemical activity are seen in the yellow to white zones in upper map. Credit: Michigan Technological University. |

To discover the importance of wolf kills to forest ecosystems, the researchers studied a 50 year record of more than 3,600 moose carcasses in the Isle Royale National Park. Isle Royale—an island on Lake Superior—is famous for its well-researched relationship between wolves and moose trapped on an island.

To uncover the connection between wolf-hunting and biodiversity hotspots, the researchers measured nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium levels at sites of wolf-kills and measured that against control sites. They also surveyed the microbes and fungi near the kills and analyzed leaf tissue of the large-leaf aster, a favorite food for moose.

The contrasts between kill sites and control sites were stark: soils at kill sites had 100 to 600 percent more inorganic nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium. They also had an average of 38 percent more bacterial and fungal fatty acids, which researchers say is proof of increased growth of bacteria and fungi in the area, while nitrogen levels in plants at kill sites were 25 to 47 percent higher than control.

These kill sites soon become foraging sites for moose attracted to the rich level of nitrogen in the plants. The foraging moose then add more nutrients due to their urine and feces.

Canis lupus or the gray wolf. Photo courtesy of the USGS. |

“I was initially skeptical that it would be possible to detect something as diffuse in the forest floor as nutrients from dead animals,” said Rolf Peterson also of Michigan Technological University, who has been studying the wolves and moose of Isle Royale for decades. “It was gratifying to see Joseph [Bump] succeed in following animal-derived nutrients back into plants to enrich them in protein, ready to be eaten again.”

Other studies have confirmed the importance of top level predators to nutrient richness. In the Arctic tundra researchers have observed that muskox carcass sites affect vegetation dramatically even a decade after they are killed.

“Predation and nutrient cycling are two of the most important of all ecological processes, but they seem just about completely unrelated to one another,” John Vucetich said, also from Michigan Tech’s School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science. “Bump has led us to understand how these two seemingly disparate processes—predation and nutrient cycling—are in fact connected and connected in a most interesting way.”

Bump suggests that the new discovery of how wolves create nutrient hotspots should be apart of policy decisions.

Although human hunters are, like wolves, top-level predators, presumably they do not facilitate nutrient growth since they remove the carcasses from the environment.

Citation: Bump, J.K., Peterson, R.O., & Vucetich, J.A. 2009. Wolves modulate soil nutrient heterogeneity and foliar nitrogen by configuring the distribution of ungulate carcasses. Ecology. Vol 90, Issue 11.

Related articles

Idaho to allow 25 percent of its wolf population to be killed in one season

(08/19/2009) The state of Idaho has set a quota of 220 individuals for the wolf hunting season which begins on September 1st. If the quota a quarter of Idaho’s estimated 880 wolves will be killed.

As wolves face the gun, flawed science taints decision to remove species from ESA

(05/07/2009) On Monday the gray wolf was removed from the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in Idaho and Montana, two states that have protected the wolf for decades. According to the federal government the decision to remove those wolf populations was based on sound conservation science—a fact greatly disputed in conservation circles. For unlike the bald eagle, whose population is still rising after being delisted in 1995, when the wolf is removed from the ESA it will face guns blazing and an inevitable decline.

When in season, wolves choose salmon over deer

(09/02/2008) The popular image of hunting wolves is a pack bearing down on a deer, working in concert to make the kill. However, new research has discovered that when available, wolves largely forgo hoofed mammals for salmon.

Fewer wolves may mean fewer pronghorn in Yellowstone

(03/03/2008) As western states debate removing the gray wolf from protection under the Endangered Species Act, a new study by the Wildlife conservation Society cautions that doing so may result in an unintended decline in another species: the pronghorn, a uniquely North American animal that resembles an African antelope.

Arctic wolves caught on tape displaying new hunting behvaior

(01/31/2008) The BBC Natural History unit has captured footage of the Artic wolf swimming for its meal. The camera crew were filming a documentary entitled White Falcon, White Wolf on Ellesmere Island, a part of the Canadian territory of Nunavut, when they spotted this never-before-seen behvaior.

Wolves push out coyotes in wilderness areas

(09/11/2007) Coyote densities are more than 30 percent lower in areas they share with wolves, according to a paper published in the most recent edition of the Journal of Animal Ecology. The results show that wolves limit the range and number of coyotes in an area.