Physician Christopher Herndon explores how Amazon shamans diagnose and treat disease.

Ethnobotanists, people who study the relationship between plants and people, have long documented the extensive use of medicinal plants by indigenous shamans in places around the world, including the Amazon. But few have reported on the actual process by which traditional healers diagnose and treat disease.

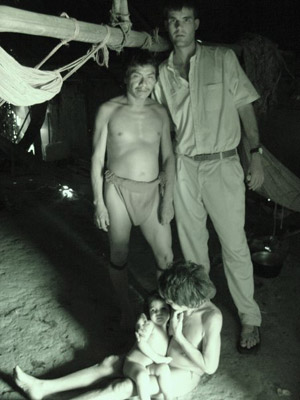

Christopher Herndon with Eñepa healer and family, Venezuela |

A new paper, published in the Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, moves beyond the cataloging of plant use to examine the diseases and conditions treated in two indigenous villages deep in the rainforests of Suriname. The research, which based on data on more than 20,000 patient visits to traditional clinics over a four-year period, finds that shamans in the Trio tribe have a complex understanding of disease concepts, one that is comparable to Western medical science. Trio medicine men recognize at least 75 distinct disease conditions—ranging from common ailments like fever [këike] to specific and rare medical conditions like Bell’s palsy [ehpijanejan] and distinguish between old (endemic) and new (introduced since contact with the outside world) illnesses.

The knowledge and treatments of shamans is the product of their own scientific method, accumulated from a progressive cycle of trial, experiment and observation repeated over countless generations. It may not be transmitted in Science or Nature but in many ways is fundamentally based on the very same empirical and pragmatic principles as Western science.

Lead author Christopher Herndon, currently a reproductive medicine physician at the University of California, San Francisco, says the findings are a testament to the under-appreciated healing prowess of indigenous shamans.

“Our paper contests a prevailing view in the medical establishment that we, as scientists, have nothing left to learn from so-called ‘primitive’ societies,” he told mongabay.com. “Our ‘Western’ medical system is itself but a compendium of knowledge, wisdom and therapeutics accumulated from past cultures and societies from around the world. We should be justifiably proud of the accomplishments of medical science, but at the same time not lose perspective that these advancements, in many cases, emerged only in the past half-century. My point is that we should not be so quick to sever the umbilical cord of our medical system from the womb of the last remaining cultures that helped gave it birth. We do so at our great loss.”

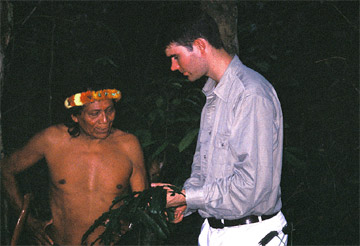

Amasina, a Trio shaman in Suriname and co-author on the Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine paper. Photo courtesy of the Amazon Conservation Team. |

Shamanism is a product of accumulated knowledge of past generations as well as deep ties—spiritual and physical—to the natural environment. But in a world where forests are being rapidly destroyed and profound cultural transformation is occurring among younger generations in traditional societies, the healing knowledge of shaman is disappearing. Among the Trio, the trajectory was accelerated by the missionaries who initially demonized shamanic practices, ostracizing healers from their communities and leaving an entire generation without the traditional apprentice/mentor relationship that is the basis for passing on knowledge from tribal elders to youths.

But the situation is changing for the Trio, thanks in part to the pioneering efforts of the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT), a “biocultural” conservation group that collaborated with Herndon (together with a Trio shaman named Amasina and the Suriname Ministry of Health) on the research. ACT has established a system of traditional health clinics to improve healthcare and promote medicinal plant knowledge among younger members of the tribe by bridging the gap between youths and healers (the average age of shaman in the study was 68, an approximate age as all were born prior to contact).

“One cannot ‘save’ the medical systems of indigenous tribes alone through written inventories of their medical plant knowledge,” Herndon explained. “Trio ethnomedicine, not unlike our healing tradition, is a complex art of diagnosis, examination, communication, ritual and treatment that can only be transmitted through active practice. The disintegration of traditional systems of health is most devastating to indigenous peoples, who at the same time often have very limited access to extrinsic medical resources. The adoption by organizations of programs that strengthen and retain tribal peoples’ self-sufficiency is critical for their health as well as to enable the transmission of these remarkable medical systems for the benefit of future generations.”

In a November 2009 interview with mongabay.com, Herndon discussed his research, the diagnostic practices and healing power of shamans, and the importance of biocultural conservation in the Amazon.

AN INTERVIEW WITH CHRIS HERNDON

Mongabay: What is your background and how did you become interested in healing practices of indigenous shamans?

Paramount shaman of the Sikiyana tribe in Suriname rainforest teaching Herndon treatment for kidney infections |

Christopher Herndon: My background as a physician in studying indigenous shamans was uncommon. Since early childhood, I have been fascinated by the rainforest, its botany and natural history. I have grown orchids since I was eight years old and spent much of my time at that age trying to convert various parts of my parents’ house into a jungle. When I was twelve years old, my great aunt, herself half American Indian and a former backwoods guide, would take me on treks through the swamps and hammocks of Southern Florida teaching me the names of plants and their historical uses. In college, these interests began to connect with my path in medicine as I became aware of how many important pharmaceuticals had been discovered through the study of the medicinal plants of tribal cultures and how rapidly this accumulated knowledge was being lost with acculturation.

Mongabay: How did you come to work with the Trio in a remote part of the Amazon?

Christopher Herndon: No region captured my fascination more than Amazonia, the world’s greatest expanse of rainforest and repository of botanical diversity. In medical school, I became involved with the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT), an organization based in Arlington, Virginia, founded by Mark Plotkin and a small handful of leading conservationists. Plotkin was a student of the great ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes and had worked for over twenty years with the Trio, a tribe inhabiting the remote headwaters of the Suriname Amazon.

|

Mark Plotkin with Amasina. Photo courtesy of the Amazon Conservation Team.

|

Following the tradition of his mentor, Plotkin had devoted the focus of his life toward the cultural and environmental protection of the indigenous peoples he studied. I had the opportunity to meet him when he was lecturing at Harvard. I waited afterwards until the crowds had thinned to talk with him. We discussed a potential project that would build upon ACT’s existing conservation initiatives in the Trio villages. The project involved establishment of traditional medicine clinics – operated and directed by tribal shamans – where the elder shamans could formally practice their medicine and apprentices could learn to enable transmission of that knowledge.

I spent my first summer of medical school deep in the Suriname rainforest working closely with the Trio shamans developing this project, at the same time learning about their medical practices and use of medicinal plants. It was the start of a journey that would carry through a decade.

Mongabay: How were you treated by the Trio? Did the shamans find it strange to be observed by a Westerner?

Christopher Herndon: I think from Plotkin’s earlier work, the Trio had become accustomed to outside interest in their botanical knowledge. They seemed quite surprised, however, to find a pananakiri (foreigner) interested in their understanding of disease and diagnostic techniques as healers. The shamans responded at first to my eagerness to learn with more of a skeptical curiosity than anything else. Over time, our relationship deepened and we would spend hours each day discussing diagnosis and management of disease conditions. They shared with me their approaches to the evaluation and examination of patients. On treks in the rainforests, they taught me not only their use of medicinal plants, but also their chants and rituals, which had long been suppressed by the missionaries.

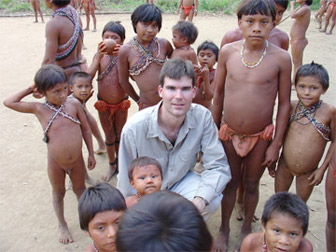

Christopher Herndon with Hoti children, Venezuela |

At the same time, they recognized my own knowledge and experience as a training physician and began to ask me about certain conditions that they had encountered. For example, a shaman related one afternoon that he noted a pulsating mass, described as “beating like a heart”, in the abdomen of an elderly woman. He commented that he had only seen it a couple times before in the past and gestured with his finger in the figure of a small cross over the umbilicus to indicate its distribution. I had a pretty good idea what condition he was referring to but, on examination of the patient in the shaman’s hut the following morning, the finding was subtle and I did not immediately appreciate it. The elder shaman guided my hand to a deeper palpation and a small pulsating aortic aneurysm was detected. The patient was examined a short time later by the circulating physician visiting in the village and he missed it also the first time!

I always approached the shamans – whom I referred to as tamo (grandfather) – with the respect and humility of a student, an apprentice. I think our paper is a testament to the trust and close partnership we maintained with our indigenous colleagues from the start of the project.

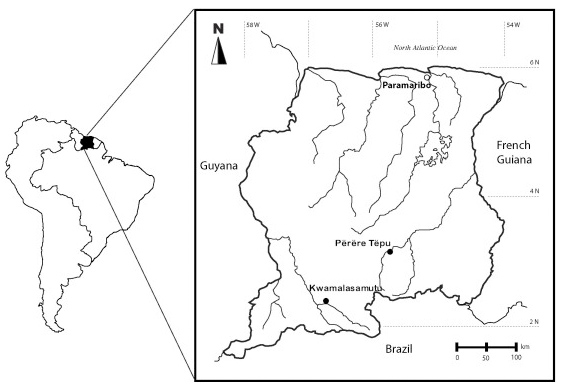

Location of the study sites. |

Mongabay: In what ways was your study built on prior work examining Amazonian shamanism?

Christopher Herndon: Scientists often approach the study of other cultures with the tunnel-vision of their own specialty training. To understand these complex healers – who are the tribal equivalent of physician, herbalist, psychiatrist and priest – one needs to look through a broader lens.

Kwamalasamutu (“Kwamala”) |

Most ethnobotanical studies had focused on the inventory and identification of medicinal plants. Tribal pharmacopeias derived through these inventories commonly number in dozens, if not hundreds, of plant species. Anthropologists were largely interested in broader concepts of health and the role of shamans in culture as healer-priests. Despite its fundamental relevance, few scientists had attempted to examine their understanding of disease or to describe indigenous diagnostic concepts.

This dearth of scientific studies contributed to a widely-held perception that the medical knowledge of tribal shamans was ‘primitive’ in comparison to their more recognized abilities, such as sophisticated empiric plant chemists. Retrospectively, it made no sense that these healers would possess such incredible therapeutic knowledge without a well-developed understanding of disease to guide their use.

Mongabay: What are the results of your work? What type of illness did the Trio shamans treat?

Jonathan, head of the indigenous park guard program for Kwamalasamutu, on patrol in the Amazon rainforest. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

Christopher Herndon: Our study was the first to examine patterns of actual disease recognition and treatment by healers of an Amazonian tribe. Its findings demonstrate a previously unappreciated sophistication of medical knowledge by tribal shamans. In our paper, we describe well over 70 disease conditions and over 120 anatomical terms. Perhaps not surprisingly, Trio shamans treat diseases common to the jungle regions in which they live. Many of their disease concepts are quite similar to our own. A few conditions, however, were culturally-specific concepts that had no readily identifiable direct biomedical correlate.

In our interviews, Trio shamans presented highly detailed and specific descriptions of disease characteristics and associated symptomatology. They frequently commented on disease associations and responsiveness to therapy, often demonstrating a remarkable insight into the natural history of disease processes as we understand them. Most significantly, we recorded the same knowledge from shamans from distant Trio villages indicating the presence of a highly formalized and conserved medical institution within the tribe.

Mongabay: Did the Trio treat any ‘new’ diseases (i.e. diseases that have been introduced since first contact)?

|

Amasina. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

|

Christopher Herndon: As with other tribes, the Trio distinguish between endemic diseases and those introduced by foreigners, such as severe malaria, tuberculosis, and influenza. Trio shamans treat these ‘new’ diseases, but are the first to tell you that their medicines are not as effective as our own treatments. Their inability to manage these conditions during the devastating pandemics that followed first contact with outsiders contributed in part to their loss of standing in the tribe. Today, shamans generally refer patients with severe malaria to the primary care clinic health outpost for a malaria smear and medication. At the same, medical workers at the village health outposts recognize that Trio treatments for certain endemic diseases, such as leishmaniasis, a tropical skin condition, seem to be as efficacious and better tolerated than the medications they can offer. For such conditions, they usually now refer these patients to the shaman. In this way, the Trio people get the benefit of the best from both systems.

Mongabay: Are we any closer to understanding how they gained this wealth of information? Who do shamans credit for their knowledge?

Christopher Herndon: Learning from an elder shaman is not that different from being taught by a silver-haired, bow-tied professor on the wards of our own medical institutions. The knowledge and wisdom the elder shamans possess are those which can only be derived through a lifetime of experience in treating patients. This is precisely why the medical systems of these tribes, in which healing knowledge is usually specialized to just a few individuals, are so fragile. The apprenticeship of a shaman can last many years. Speaking as someone still in postgraduate fellowship training, now six years from medical school, perhaps our system may not be so different as we might like to think!

Mongabay: What can Western medicine learn from your findings and more generally, indigenous healing practices?

Kayapo shaman in Brazil. |

Christopher Herndon: Our paper contests a prevailing view in the medical establishment that we, as scientists, have nothing left to learn from so-called ‘primitive’ societies. Our ‘Western’ medical system is itself but a compendium of knowledge, wisdom and therapeutics accumulated from past cultures and societies from around the world. We should be justifiably proud of the accomplishments of medical science, but at the same time not lose perspective that these advancements, in many cases, emerged only in the past half-century. My point is that we should not be so quick to sever the umbilical cord of our medical system from the womb of the last remaining cultures that helped gave it birth. We do so at our great loss.

Mongabay: Can you cite an example?

Christopher Herndon: Beyond therapeutics, one aspect is the shaman’s ability to communicate with patients and to engage them as participants, rather than subjects, in the healing process. Despite the great technological successes of modern medicine, thousands of patients in our country feel increasingly disenfranchised by the medical system and, more broadly speaking, there is a sense of devaluing of the doctor-patient relationship. Patients – often highly intelligent and informed individuals – not uncommonly seek something else and reach out for diverse array of complementary and alternative medicines which are not well established. The rare chance to learn from these elder Amazonian shamans, as one colleague remarked to me, is the opportunity to enroll in one of the greatest training programs for complementary and alternative medicine. They are among the last remaining masters of their ancient craft.

Mongabay: Your research took place among the Trio in Suriname but have you observed shamanic practices in other parts of the Amazon? Did you see differences?

Christopher Herndon: Over the past decade, I had the opportunity to work with healers from a wide diversity of tribes throughout Amazonia. The medical systems of each tribe are different. In some tribes, shamans utilize plants which might be considered hallucinogens in our science to connect with the spiritual world to seek a diagnosis. In one nomadic hunter / gather group, medicinal knowledge is not strictly specialized to a central shamanic figure, but rather disseminated more broadly throughout the tribe. Beyond these differences, I witnessed a shared commonality among the indigenous healers in their remarkable sophistication of medical knowledge and skills. Moreover, I found them willing to share their knowledge, when approached with respect, as well as having an intellectual curiosity regarding our own system of healing.

Mongabay: Missionaries discouraged traditional practices after they settled among the Trio. Was there any persecution of healers? Are there any signs that knowledge has been lost as a result of this?

Herndon evaluating a sick child with Eñepa healer, Venezuela |

Christopher Herndon: Fortunately, for the Trio, the time interval from sustained contact was relatively brief. I do not believe that this knowledge was significantly lost but certainly had been teetering on the brink of extinction. Most of the shamans were around seventy years of age and were born decades prior to contact. The evangelical missionaries who had originally contacted the tribe primarily took issue with what they termed the “witchcraft” or “sorcery” aspects of shamanism, which they could not see quite in line with their new converts’ full acceptance of the Gospel. At the same time, they lived closely enough with the tribe to recognize that some of their medicinal plants were actually quite effective. The missionaries attempted to divorce the “sorcery” aspects of shamanism from all the other aspects of their medical system, albeit unsuccessfully, because the Trio healing system is far more holistic and not so neatly compartmentalized.

Mongabay: How are healers viewed in communities today?

Christopher Herndon: One of the most satisfying aspects of my work with the traditional clinic program was observing the elder shamans restored to positions of honor in the villages. At the opening ceremony of the first clinic, an elder Trio shaman stood up and proclaimed it was the first time in thirty years that he could publicly acknowledge he was a shaman. In more acculturated indigenous communities I visited in Suriname and elsewhere, there usually was either no longer a shaman remaining or their traditional medical system comprised a single individual marginalized to the outskirts of the village, long inactive as a healer and forgotten by the tribe.

The traditional clinic program among the Trio went on to be a tremendous success – receiving thousands of visits over several years – a comparable number as the village health outpost. The program was subsequently successfully replicated in two other tribes in Suriname and received international recognition. I believe keys to its success were the full autonomy of the elder shamans in directing its operation as well as the strong partnership with Medische Zending Suriname, the regional health care provider.

Mongabay: What do you see as the best way to retain indigenous knowledge that is increasingly lost due to cultural transformation and assimilation?

Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

Christopher Herndon: The need for preservation of medicinal plant knowledge is often cited as a compelling argument for biocultural conservation and ethnobotany in particular. One cannot ‘save’ the medical systems of indigenous tribes alone through written inventories of their medical plant knowledge. Trio ethnomedicine, not unlike our healing tradition, is a complex art of diagnosis, examination, communication, ritual and treatment that can only be transmitted through active practice. The disintegration of traditional systems of health is most devastating to indigenous peoples, who at the same time often have very limited access to extrinsic medical resources. The adoption by organizations of programs that strengthen and retain tribal peoples’ self-sufficiency is critical for their health as well as to enable the transmission of these remarkable medical systems for the benefit of future generations.

AUTHORS: Christopher N Herndon, University of California, San Francisco; Melvin Uiterloo, Amazon Conservation Team Suriname; Amasina Uremaru, Trio indigenous community of Kwamalasamutu, Sipaliwini District, Suriname; Mark J Plotkin, Amazon Conservation Team; Gwendolyn Emanuels-Smith, Amazon Conservation Team Suriname; and Jeetendra Jitan, Ministry of Health, Paramaribo, Suriname.

CITATION: Herndon et al. Disease concepts and treatment by tribal healers of an Amazonian forest culture. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2009 5:27 doi:10.1186/1746-4269-5-27

Related articles

An interview a shaman in the Amazon rainforest

(07/28/2008) Deep in the Suriname rainforest, an innovative conservation group is working with indigenous tribes to protect their forest home and culture using traditional knowledge combined with cutting-edge technology. The Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) is partnering with the Trio, an Amerindian group that lives in the remote Suriname-Brazil border area of South America, to develop programs to protect their forest home from illegal gold miners and encroachment, improve village health, and strengthen cultural ties between indigenous youths and elders at a time when such cultures are disappearing even faster than rainforests. In June 2008 mongabay.com visited the community of Kwamalasamutu in Suriname to see ACT’s programs in action. During the visit, Amasina, a Trio shaman who works with ACT, answered some questions about his role as a traditional healer in the village.

Amazon Conservation Team wins “Innovation in Conservation Award” for path-breaking work with Amazon tribes

(12/11/2007) The Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) was today awarded mongabay.com’s inaugural “Innovation in Conservation Award” for its path-breaking efforts to enable indigenous Amazonians to maintain ties to their history and cultural traditions while protecting their rainforest home from illegal loggers and miners.

Amazon rainforest children to get medicinal plant training from shamans

(11/21/2007) The Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) — a group using innovative approaches to preserving culture and improving health among Amazonian rainforest tribes — has been awarded a $100,000 grant from Nature’s Path, an organic cereal manufacturer. The funds will allow ACT to address one of the most pressing social concerns for Amazon forest dwellers by expanding its educational and cultural “Shamans and Apprentice” program for indigenous children in the region.

|

Amazon Indians use Google Earth, GPS to protect forest home

(11/14/2006) Deep in the most remote jungles of South America, Amazon Indians are using Google Earth, Global Positioning System (GPS) mapping, and other technologies to protect their fast-dwindling home. Tribes in Suriname, Brazil, and Colombia are combining their traditional knowledge of the rainforest with Western technology to conserve forests and maintain ties to their history and cultural traditions, which include profound knowledge of the forest ecosystem and medicinal plants. Helping them is the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT), a nonprofit organization working with indigenous people to conserve biodiversity, health, and culture in South American rainforests.

|

Indians are key to rainforest conservation efforts says renowned ethnobotanist

(10/31/2006) Tropical rainforests house hundreds of thousands of species of plants, many of which hold promise for their compounds which can be used to ward off pests and fight human disease. No one understands the secrets of these plants better than indigenous shamans -medicine men and women – who have developed boundless knowledge of this library of flora for curing everything from foot rot to diabetes. But like the forests themselves, the knowledge of these botanical wizards is fast-disappearing due to deforestation and profound cultural transformation among younger generations. The combined loss of this knowledge and these forests irreplaceably impoverishes the world of cultural and biological diversity. Dr. Mark Plotkin, President of the non-profit Amazon Conservation Team, is working to stop this fate by partnering with indigenous people to conserve biodiversity, health, and culture in South American rainforests. Plotkin, a renowned ethnobotanist and accomplished author (Tales of a Shaman’s Apprentice, Medicine Quest) who was named one of Time Magazine’s environmental “Hero for the Planet,” has spent parts of the past 25 years living and working with shamans in Latin America. Through his experiences, Plotkin has concluded that conservation and the well-being of indigenous people are intrinsically linked — in forests inhabited by indigenous populations, you can’t have one without the other. Plotkin believes that existing conservation initiatives would be better-served by having more integration between indigenous populations and other forest preservation efforts.

How did rainforest shamans gain their boundless knowledge on medicinal plants?

(5/14/2005) For thousands of years, indigenous people have extensively used rainforest plants for their health needs — the peoples of Southeast Asian forests used 6,500 species, while Northwest Amazonian forest dwellers used 1300 species for medicinal purposes. Perhaps more staggering than their boundless knowledge of medicinal plants, is how shamans and medicinemen could have acquired such knowledge. There are over 100,000 plant species in tropical rainforests around the globe, how did indigenous peoples know what plants to use and combine especially when so many are either poisonous or have no effect when ingested. Many treatments combine a wide variety of completely unrelated innocuous plant ingredients to produce a dramatic effect.