It sounds like something out of Greek mythology: a half-goat, half-reptilian creature. But researchers have discovered that an extinct species of goat, the Balearic Island cave goat or Myotragus balearicus, survived in nutrient-poor Mediterranean islands by evolving reptilian-specific characteristics. The goat, much like crocodiles, was able to grow at flexible rates, stopping growth entirely when food was scant. This adaptation—never before seen in a mammal—allowed the species to survive for five million years before being driven to extinction only 3,000 years ago, likely by human hunters.

Islands, especially nutrient-poor islands, are usually home to reptiles. Mammals are endotherms, meaning that they have steady and high growth rates, and therefore require rich environments to sustain them. However reptiles, ectotherms, grow slowly and are able to change their growth rates when resources fluctuate, making them perfectly adaptable to resource-poor islands, like the Balearic islands of Spain. So, given the environmental conditions of these islands, how did a species of goat thrive there for millions of years?

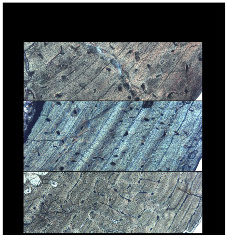

Bone tissue records the physiological and life history strategies of fossil organisms. Ectotherms are characterized by zonal bone with cyclical growth rings (above); endotherms typically have azonal, highly vascularized bone (below). The presence of ectotherm bone tissue in a fossil insular bovid (middle) denotes that under certain environmental conditions mammals may evolve reptile-like developmental and physiological plasticity. Image courtesy of Institut Català de Paleontologia ICP (Catalan Institute of Paleontology). |

This question led researchers Meike Kohler and Salvador Moya-Sola from the Catalan Institute of Paleontology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona to analyze the fossil bones of the Balearic Island cave goat. What they found was nothing short of shocking.

“The bone microstructure indicates that Myotragus grew unlike any other mammal but similar to crocodiles at slow and flexible rates, ceased growth periodically, and attained [physical] maturity extremely late by 12 years,” Kohler and Moya-Sola write in a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

While the Balearic Island cave goat is the world’s first mammal known to have adapted reptilian growth strategies, Kohler and Moya-Sola believe there were probably others. The Balearic Island cave goat was a dwarf species: standing only 50 centimeters (19.5 inches) at the shoulder, smaller than a medium-size dog. Only a few thousands years ago, Mediterranean islands were also home to a variety of dwarf mammals, including elephants, hippos, and deer. Kohler and Moya-Sola hypothesize that these other dwarf mammals must have evolved traits similar to the Balearic Island cave goat—and reptiles—in order to survive in low nutrient environments.

Yet, as Kohler and Moya-Sola write it was likely these same traits that led to the species’ downfall.

“The reptile-like physiological and life history traits found in Myotragus were certainly crucial to their survival on a small island for the amazing period of 5.2 million years, more than twice the average persistence of continental species. […] However, precisely because of these traits (very tiny and immature neonates, low growth rate, decreased aerobic capacities, and reduced behavioral traits), Myotragus did not survive the arrival of a major predator, Homo sapiens, some 3,000 years ago,” they write.

Citation: Meike Kohler, Salvador Moya-Sola. Physiological and life history strategies of a fossil

large mammal in a resource-limited environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

Reconstruction of Myotragus balearicus at Cosmo Caixa, Barcelona. Photo: Xavier Vázquez.

Skeleton of Myotragus balearicus. Photo: Francisco Valverde.

Related articles

World’s largest snake discovered: prehistoric serpent was twice the size of an anaconda

(02/04/2009) Paleontologists have recently uncovered the world’s largest snake announces a paper in Nature. Measuring an astonishing 42 to 45 feet, the Titanoboa cerrejonensis makes the anaconda look diminutive. In fact the prehistoric serpent even makes once-ridiculous horror movie snakes appear conservative. “Truly enormous snakes really spark people’s imagination, but reality has exceeded the fantasies of Hollywood,” said Jonathan Bloch, one of the leaders of the party that discovered the prehistoric serpent. “The snake that tried to eat Jennifer Lopez in the movie Anaconda is not as big as the one we found.”

Missing link between fish and land animals discovered

(11/07/2008) A study published in the October 16 issue of Nature details research

into and implications of a fossil fish, Tiktaalik roseae, discovered

last year at Ellesmere Island in Canada. The Devonian fossil shows an

array of features found in both terrestrial and aquatic animals,

providing the best glimpse so far into the transitory period during

which vertebrates were able to adapt to life out of water. The find

provides some of the first osteological evidence of neck development,

a crucial adaptation to terrestrial life because it allows an animal’s

body to remain stationary while it surveys its environment.

Humans – not climate – drove extinction of giant Tasmanian animals

(08/11/2008) Humans — not climate change — were responsible for the mass extinction of Australia’s megafauna, according to a new study published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

10-pound ‘Giant Frog From Hell’ discovered in Madagascar

(02/18/2008) Researchers have discovered the remains of what may be the largest frog ever to exist.

(01/16/2008) Scientists have discovered the remains of an extinct 2,000 pound rodent — the largest rodent ever known. The find is described Wednesday in Britain’s Proceedings of the Royal Society.

Despite Arctic crocodiles, glaciers existed during extreme global warming 90M years ago

(01/10/2008) Massive glaciers extended across 50-60 percent of Antarctica some 91.2 million years even as crocodiles roamed the Arctic and surface temperatures of the western tropical Atlantic Ocean climbed to 37 degrees Celsius (98 degrees Fahrenheit), reports a study published in the journal Science.