How youth in Kenya’s largest slum created an organic farm

An interview with an organic pioneer, Su Kahumbu

Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com

December 9, 2008

Kibera is one of the world's largest slums, containing over a million people and one third of Nairobi's population. With extremely crowded conditions, little sanitation, and an unemployment rate at 50 percent, residents of Kibera face not only abject poverty but also a large number of social ills, including drugs, alcoholism, rape, AIDS, water-borne diseases, and tensions between various Kenyan tribes.

However, the majority of Kibera's residents are just trying to live as well as possible under daunting circumstances. Proving that optimism and entrepreneurship are very much alive there, in July of this year the slum's only organic farm began selling its first harvest of ripe green spinach and kale, while sunflowers unfurl upward from soil that had once been a garbage dump. The idea of the farm came from boys and girls in Kibera's Youth Reform Program. They had the vision and the ambition, but in order to make their dream a reality they needed help.

|

Su Kahumbu in front (Paula Kahumbu) |

Su Kahumbu, a tireless advocate of organic farming in Kenya, was quickly enlisted. Her participation came with one request: it must be an organic farm. Kahumbu is a true pioneer in Kenya. In 2004 her farm was the first in the nation to receive organic certification. Since then her organization, Green Dreams, Ltd. (greendreams.edublogs.org), has started up several successful organic groceries in Nairobi, and Kahumbu campaigns continually for small farmers and the promise of organic farming in Africa.

But how does anyone turn a garbage dump into an organic farm? "It started with the removal of the garbage," Kahumbu told Mongabay.com. "This was done physically and took three weeks! From there we started the seed beds as we prepared the growing beds on the cleared land. The beds were dug up and levelled before adding farmyard manure… Drip irrigation and a water tank were installed just as the seedlings were ready to be transplanted, after which the transplanting was done. Later we added a vermiculture set- up. And all the while the guys were learning how to tend their future and budding crops. Voila!" Vermiculture refers to producing nutrient-rich organic fertilizer by composting with the help of particular species of earthworm.

|

Kenya’s slum of Kibera as taken by Google Earth. Many of the residents of Kibera have migrated here from rural lands, seeking a better life. Just north of the slum is the Royal Nairobi Golf Course. |

Kahumbu sees incredible possibilities in Kibera's small organic plot. "I think it is absolutely vital we take this example of success seriously and recognize the implications if we could cut and paste it in our African slums."

Her optimistic spirit, seemingly boundless energy, and past experiences have given Kahumbu a deep belief in the power of small farmers growing natural produce. She sees in such values a remedy for the food crisis: "The solution to the global food crisis is increased production. We have to ask ourselves why we have problems with production. We rely on the poorest of the poor to feed the world. Something is wrong. It's time farmers gained respect and fair prices for their products. We need to invest in farmer education and support so that they opt to stay in the fields and feed the world. It is a vital job."

|

Su with Victor from youth group check out the worm ‘hotel’. In a process called vermiculture worms are used to produce organic compost. (Paula Kahumbu) |

Kahumbu is not afraid to criticize policies she believes are misguided. When asked about the policies of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), she takes the organization to task for planning to import to Africa programs that haven't worked: "AGRA plans to roll out similar systems used during the Green Revolution in Asia. High fertilizer availability (subsidized), improved seed varieties as well as micro-credit to the farmers. While this may seem like a much-needed solution to increasing yields immediately, it can have disastrous long-term effects, just like in India—poorer soils, bankrupt farmers, zero diversity in food production." She believes that AGRA money would be better spent "educating farmers on sustainable methods of production, and strengthening the market linkages as well as training farmers on value addition."

Currently, Kahumbu is contemplating making a television series that will teach African farmers "how to minimize their risks, improve yields, and increase their income with organic production."

In a December 2008 interview, Kahumbu tells the story of Kibera's unlikely garden, discusses the many initiatives of her organization, Green Dreams, Inc., and explains her hopes for the future of Africa agriculture.

How reformed youth in Kenya's largest slum created an organic farm

An interview with organic pioneer, Su Kahumbu

Mongabay: How did you become interested in the environment, particularly organic farming?

|

Hassan and Su in front of Kibera’s first organic farm. (Paula Kahumbu) |

Su Kahumbu: In 1996 my family and I returned home to Kenya from a two-year stay in South Africa with the hope of setting up hydroponic farms all over the slums of Nairobi. Our prototype which we had assembled on my mother's farm failed (largely due to the fact that we had no experience in agriculture). We transplanted the seedlings from the failed system into my mother's shamba (farm) and watched them grow. We then started to market the produce and found the demand was higher than we could supply.

One unfortunate, yet ironically fortunate day, my mother was caught down drift of a lethal spray we were using on the tomatoes. She instantly became violently ill. It terrified me that this was what we were dealing with and feeding our children. That was the changing point in my mind about agriculture, food, health and the environment. From then on, until present day, I began to study and experiment with organic production.

KIBERA ORGANIC FARM

Mongabay: At first glance this project—creating an organic farm over what used to a garbage dump in Kenya's largest slum—seems impossible? How did this particular project begin? How did you get involved?

|

|

Su Kahumbu: After the post electoral violence when many Kenyans were in IDP camps, I was perturbed at the thought of the impending future food crisis if our farmers missed the coming rains. Recognising that due to the violence most folks had lost everything, I devised a plan to distribute seeds through the Red Cross network, which was already supporting the IDP camps. The seed packet was to contain a variety of fast growing nutritious crops some ready to harvest in merely six weeks. The plan was to roll out 100,000 seed packs; however, I was unable to raise the funding required.

During this time a friend approached me and asked if I would help her with a Group in Kibera who had started clearing a garbage site and wanted to turn it into a farm.

I agreed on condition it was an organic farm.

It started from there, the first seeds planted were from the demo packets we had put together for the larger project that had not taken off.

Mongabay: Can you tell us about the kids from Kibera's Youth Reform?

Su Kahumbu: The youth from the group are great. They came together a few years ago to form a support network as they chose to leave their ways of crime. They are both girls and guys between 25 and 30. They spend their days working in and around Kibera mostly doing casual work and taking part in the community events like football. I think they even have their own team.

Mongabay: What are the challenges and rewards of creating an organic farm in Kibera, Africa's second largest slum?

|

Two men from the youth group begin shoveling the garbage out of the farm site. Cleaning the whole site of trash would take three weeks. (Wakio Seaforth) |

Su Kahumbu: The challenges were largely to do with the fact that the group were not former farmers thus the risk was the whole farm may have not been sustainable. However, they were very fast learners and as the idea was theirs to begin with the sense of ownership and responsibility was very strong.

The rewards are many and still unfolding. The group has food, sells food, and seedlings thus deriving an income. The non-tangible rewards are the respect the group now has from their local community as well as all the folks who have heard about the group abroad. Of late every week another international media house has been covering the project. They have become celebrities!

Mongabay: What was the process of turning a dangerous dump into a field ready to

produce organic foods?

|

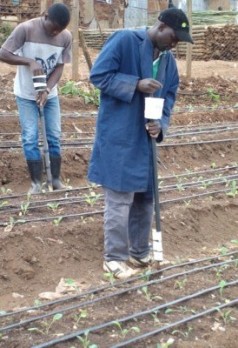

Transplanting the new seedlings. (Dominic Wanjihia)

Men from the youth group setting up a drip irrigation system.(Dominic Wanjihia) |

Su Kahumbu: It started with the removal of the garbage. This was done physically and took three weeks! From there we started the seed beds as we prepared the growing beds on the cleared land. The beds were dug up and levelled before adding farmyard manure.

Structural stuff was going on too. We fenced the plot to keep out stray dogs, geese and goats and to stop folk from continuing to use the site as a dumping area.

Drip irrigation and a water tank were installed just as the seedlings were ready to be transplanted after which the transplanting was done. Later we added a vermiculture set up. And all the while the guys were learning how to tend their future and budding crops. Voila!

Mongabay: With funds and aid could you see small organic farms sprouting up all over Kibera and other slums in Africa?

Su Kahumbu: Absolutely, yes! I think it is absolutely vital we take this example of success seriously and recognise the implications if we could cut and paste it in our African slums.

OTHER PROJECTS (AND PASSIONS) WITH GREEN DREAMS LTD.

Mongabay: You were a member of the committee that produced the Kenyan National Organic Standards. What are some of the most important standards that organic farms must abide by in Kenya to be certified?

|

Victor and Hassan use a newly developed planting tool, designed by Dominic Wanjihia (Dominic Wanjihia) |

Su Kahumbu: Yes, I was part of the committee that helped draft and push the national standards through. As with international standards, the most important aspect of the organic standards are the non use of synthetic chemicals in organic production, actually throughout the organic chain, production as well as processing and packaging.

Unfortunately, although we have the standards, we do not have policies in place to enforce them and thus there is a lot of fraudulent labelling of products in the market place. Through our networking body The Kenya Organic Agriculture Network or KOAN (an NGO) we are developing the boundaries within which ‘Organic' exists in Kenya as we try to get more government awareness and involvement.

It is imperative that for organic to grow that we get the government on board. Agriculture per se is not subsidised in Kenya. Farmers struggle. Most production is rain fed which means production twice a year. Global climate change is threatening most farmers who miss seasons of harvest due to failed and insufficient rains, or as now, too much rain. We need to harness new appropriate technologies so that we can produce 365 days of the year. Drip irrigation and shade net in my mind were the backbone of my own farm which produced 365 days a year for 8 years!

The challenge is to make this affordable and to spread the education to the farmers. Imagine the increase of food production if we could all produce 25 percent more? Just 25 percent could be the difference between abject poverty and a decent life.

I plan one day when I can get the resources to produce a series of films for African T.V stations to show farmers how to minimise their risks, improve yields and increase their income with organic production.

Mongabay: How did it feel to be the first farm to receive organic certification in

Kenya?

Su Kahumbu: Awesome! A recent UN report stated that organic farming in Africa could boost yields—acting as a buffer against famine—while creating more revenue for small impoverished farmers. These are two large benefits from organic farmers, are there others?

|

First commercial sale of produce. (Dominic Wanjihia) |

Organic is like magic. Everything under organic production changes for the better.

With regards to famine and food other important aspects include increased diversity of crops due to the nature of intercropping, companion planting etc, thus an increase in nutritional health. This impacts biodiversity at all levels, insects, crops, opportunistic plants etc.

Other grains include: improved soil fertility and soil coverage resulting in better drainage, less erosion, better ground water retention, cleaner less silted rivers, less polluted rivers. Organic requires education resulting in skills and knowledge transfer at a community level and therefore aides in community building.

On a less talked about level, organic improves the aesthetics of the land which must surely result in a feel good factor and better health. Not forgetting, organic products taste better!

Because organic products are more expensive they are less wasted, so less farm land is wasted in production. Currently tons of conventional crops, especially those for export, are trashed every day. Tons. This is an absolute waste of resources, time and fragile land use and abuse.

Mongabay: You now have two organic foods store in Nairobi, an organic magazine, and several farmers across Kenya working with the organic movement. What do you

attribute to these major successes?

Su Kahumbu: Three things: passion, passion, passion! Passion and hard work from all those involved.

Incidentally, we have now opened another four organic outlet shop-in-shop sales points in the last month alone!

Mongabay: How much has the international food crisis affected Kenya? What do you see as solutions to this global issue?

|

Young girl named Helina with rabbit who visited Su Kahumbu’s organic farm in Tigoni. (by Su Kahumbu) |

Su Kahumbu: Any international crisis affects us in the same way. Food prices increased purely because the pundits who read about the food prices increasing in abroad took advantage of the situation and raised local prices. It took a while for the food producers to do the same. I do not believe we should have been affected on local products.

The solution to the global food crisis is increased production. We have to ask ourselves why we have problems with production. We rely on the poorest of the poor to feed the world. Something is wrong. It's time farmers gained respect and fair prices for their products. We need to invest in farmer education and support so that they opt to stay in the fields and feed the world. It is a vital job.

The UN report stating that in 2030 half of the planets population will be living in urban areas is scary as hell. Most will be in slums. WHO IS GOING TO PRODUCE OUR FOOD? We must make farming more rewarding for farmers globally.

ALLIANCE FOR A GREEN REVOLUTION IN AFRICA

Mongabay: You have stated opposition against the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). The organization says that "AGRA programs develop practical solutions to significantly boost farm productivity and incomes for the poor while safeguarding the environment." What do you view as wrong with the organization?

Su Kahumbu: AGRA plans to roll out similar systems used during the Green Revolution in Asia. High fertiliser availability (subsidised), improved seed varieties as well as micro-credit to the farmers.

|

Augustine among the garden’s sunflowers. Not just planted for their beauty, the sunflowers naturally pull excess zinc out of the ground. (Paula Kahumbu) |

Whilst this may seem like a much needed solution to increasing yields immediately, it can have disastrous long term effects…just like in India: poorer soils, bankrupt farmers, zero diversity in food production.

I think AGRA would be better off using their money to educate farmers on sustainable methods of production, and strengthening the market linkages as well as training farmers on value addition.

Many developed countries have lost their small-scale farmers and rely on larger farms due to economies of scale. Africa cannot follow the same pattern. The culture and land tenure systems are different. And different in every country too.

Our farmers are called farmers by default. Many are simply folk living off their land as they lack education and opportunities to do anything else. The fear is if they are forced off their land they will end up in the ever growing slums.

Due to the cultural practices of inheritance and thus land division, many farmers have tiny plots. This is where I see the opportunities for value addition, even group systems of value addition, in order to continue to realise an income one can survive on.

Mongabay: What is wrong with particular subsidies? Should subsidies ever be used for farming?

Su Kahumbu: Nothing is wrong with subsidies until they come to an end.

Subsidising fertilizers is a mistake. The fallout when they come to an end will take us backwards, beyond square one as we will now be dealing with degraded soils.

|

Su Kahumbu and kids from Kenton College School farm visit. Su is teaching the eight-year-olds about bio-diversity. (Kenton Teacher ) |

Subsidised fertiliser can only work if the real price is factored into the selling price of the crops/products.

If not, on removal of subsidies, the prices of the goods would suddenly increase. If demand then decreases, the farmers will end up in a financial problem. The same will happen when all farmers choose the subsidised improved seed. There will suddenly be a surplus of crop and prices will fall.

Either way the economics are fragile and risks high if you look into the future. We have examples in India.

Subsidising farm inputs like hardware, irrigation, machinery is OK but risky as the maintenance of these inputs must be not only available but also affordable.

Subsidised training and education is great. I will always harp on about education. Farmers need to learn how to do the math and factor in all their costs. This is the hardest thing especially when most of our farmers are now in their fifties!

We are currently trying to put a little patch on huge wound. Lending credit to an uneducated older generation is not only risky, but factor in our culture, and it results in the possibility of land seizure when banks come knocking. It is a reality here in Kenya: as in most cases, the banks win.

We need a younger generation of educated farmers. The youth need an incentive for this to happen. It comes back to income. Prices need to be attractive. The youth need the tools to achieve this.

Real opportunities need to be made available. Value addition is imperative. Markets need to be opened locally, regionally as well as internationally and trade barriers need removing.

Mongabay: What are your future plans?

|

A training session in Kigogo Gilgil. Local farmers are learning about drip irrigation. (Su Kahumbu) |

Su Kahumbu: I plan to be as instrumental as possible in developing organic agriculture and value addition, thus improving income generation, for Africa's small scale farmers and Africa's fragile environment.

I am not a PHD or even degree holder, but hope that even so my work can be recognised at a level that will allow me to make a positive change at a national level for my country.

Mongabay: Finally, this may be a little off topic, but I feel compelled to ask: in the

United States we have been hearing a lot regarding Kenya's excitement over the election of Barack Obama. What do you think Obama's election means to

Kenya?

Su Kahumbu: In a nut shell, I think Obama's election has left a feeling of ‘if he can, and he is partly Kenyan …then YES, WE CAN!'

Naturally we hope that his policies result in a better understanding and relationships between such a huge developed nation as the US, and developing nations like ours.

For more information on Green Dreams Ltd. and the project in KiberiaKibera: