Forest elephants learn to avoid roads, behavior may lead to population decline

Forest elephants learn to avoid roads, behavior may lead to population decline

Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com

October 27, 2008

Forest elephants in the Congo Basin have developed a new behavior: they are avoiding roads at all costs. A study published in PLoS One concludes that the behavior, which includes an unwillingness to cross roads, is further endangering the rare animals which are already threatened by poaching, development, and habitat loss. By avoiding roads, the elephants are increasingly confining themselves to smaller areas lacking enough habitat and resources.

Scientists with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and Save the Elephants believe the pachyderms are avoiding roads because the highly-intelligent animals have connected roads with poachers. This is not surprising, considering a study which found that elephants that had negative encounters with humans learned rapidly to fear and avoid them, and passed this knowledge down to their young. Although the behavior probably helps the elephant avoid poaching, scientists believe the negative consequences of the behavior far outweigh the positive.

Whole communities of elephants are stuck in what has been described as a “virtual prison”. The smaller the prison is, the less access to food and vital mineral deposits. Researchers worry that a lack of resources will lead to high-levels of aggression and stress in elephant communities, which is likely to cause declines in reproduction. In addition, the roadway barriers will have an impact on the ecosystem of the tropical forest, since elephants are key seed dispersal agents for regenerating forests.

New road in Central Africa (credit: Stephen Blake). |

“Forest elephants are basically living in fear of their lives in prisons created by roads. They are roaming around the woods like frightened mice rather than tranquil formidable giants of their forest realm," Dr. Stephen Blake, the study's lead author, explained. "Forest elephants are under siege with all of the graphic images that go with it – increasing the likelihood of fear, starvation, disease, massive stress, infighting, and social disruption."

Tracking 28 forest elephants using GPS collars, the study found that elephants were most wary of roads outside of protected areas—those likeliest to harbor poachers. Of the 28 elephants, only one crossed a road outside a protected area. The authors note that it didn’t walk, but ran breakneck across the road at a speed 14 times its regular pace. Although wariness was greatest around roads outside protected areas, the researchers saw adverse reactions to roads everywhere.

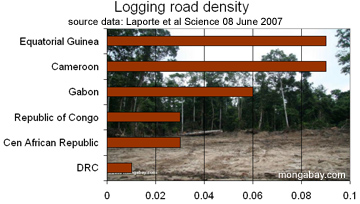

Logging road density in Congo count |

Unfortunately for elephants, roadless area continues to decline in the Congo Basin. Between the time of the study’s data collection and its publication, the authors report that three of their six study sites have seen large-scale road-building. Multi-billion dollar development projects, which include extensive road building, are currently in the works. The scientists predict that an increase in road-building will directly correlate with a decline in forest elephant populations. However, Blake hopes that smarter planning could aid both elephants and locals.

"A small yet very feasible shift in development planning, one that is actually good for poor local forest people and for wildlife and wilderness, would be a tremendous help to protect forest elephants and their home,” Blake said. “Planning roads to give forest elephants breathing space so that at least those in the deep forest can relax, as well as reduce the death and fear that comes with roads by reducing poaching, would be trivial in terms of cost but massively important for conservation."

Forest elephant in Gabon (credit: Rhett Butler) |

The elephants’ remarkable reasoning—connecting roads with deadly poachers—is in line with other studies recording the intelligence of the world’s largest terrestrial mammals. Breaking off sticks and using them to scratch themselves or swat at flies, elephants have proven they can make and use tools (a skill once thought to be unique to humans). When a member of the elephant community dies, the rest participate in what appears mourning ritual, touching the body with their trunks and trumpeting for days. Such a display of empathy requires high intelligence. In addition, elephants are one of the few animals—along with apes, dolphins, and magpies—to recognize itself in a mirror.

Recent DNA research has sparked off a debate as to whether or not Africa’s forest elephants are a subspecies of the better known African savannah elephants or a different species entirely. The African forest elephant is certainly smaller than their savannah cousins. In addition, they sport a longer and narrower lower jaw, possess straighter tusks with a pinkish hue, and usually have an extra toenail on each foot. Whether the forest elephant is a subspecies or its own species could have large conservation implications.

Related articleS

African elephants being poached at record rate August 1, 2008

African elephants are being killed for their ivory at a record pace, reports a University of Washington conservation biologist. Samuel Wasser says the elephant death rate from poaching throughout Africa is currently about 8 percent a year — higher than the 7.4 percent annual death rate that led to the international ivory trade ban nearly 20 years ago.

Congo forest elephants declining from logging roads, illegal ivory April 1, 2007

Fast-expanding logging roads in the Congo basin are becoming “highways of death” for the fierce but elusive forest elephant, according to a new study published in the journal Public Library of Science. Logging roads both provide access to remote forest areas for ivory poachers and serve as conduits of advancing human settlement.

Logging roads rapidly expanding in Congo rainforest June 7, 2007

Logging roads are rapidly expanding in the Congo rainforest, report researchers who have constructed the first satellite-based maps of road construction in Central Africa. The authors say the work will help conservation agencies, governments, and scientists better understand how the expansion of logging is impacting the forest, its inhabitants, and global climate.