Sea ice loss may triple warming over northern Alaska, Canada, and Russia

Sea ice loss may triple warming over northern Alaska, Canada, and Russia

mongabay.com

June 11, 2008

Fast-declining Arctic sea-ice could spur rapid warming in northern Alaska, Canada, and Russia triggering thawing of permafrost and a release greenhouse gases from the frozen soils, reports a new study published in Geophysical Research Letters.

“Our study suggests that, if sea-ice continues to contract rapidly over the next several years, Arctic land warming and permafrost thaw are likely to accelerate,” said lead author David Lawrence of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

The research, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation, looked at whether last summer’s unusually low sea-ice extent — more than 30 percent below average — and warm land temperatures — more than 2 degrees C above the 1978-2006 average — were related. Using computer models to simulate the effects of rapid sea-ice loss, the researchers found that Arctic land warms at a rate 3.5 times greater than the average 21st century warming rates predicted in global climate models. The warming, which is most pronounced over ocean areas, can extend up to 900 miles inland. The findings suggest that autumn temperatures — when sea-ice extent is at its lowest — could rise as much as 9 degrees F (5 degrees C) along the Arctic coasts of Russia, Alaska, and Canada during extended sea-ice-loss events.

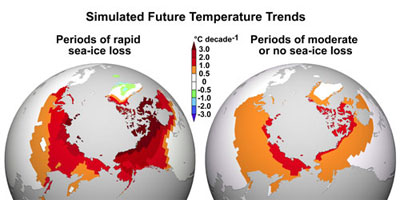

Accelerated Arctic warming. Simulations by global climate models show that when sea ice is in rapid decline, the rate of predicted Arctic warming over land can more than triple. The image at left shows simulated autumn temperature trends during periods of rapid sea-ice loss, which can last for 5 to 10 years. The accelerated warming signal (ranging from red to dark red) reaches nearly 1,000 miles inland. In contrast, the image at right shows the comparatively milder but still substantial warming rates associated with rising amounts of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere and moderate sea-ice retreat that is expected during the 21st century. Most other parts of the globe (in white) still experience warming, but at a lower rate of less than 1 degree Fahrenheit (0.5 Celsius) per decade. |

The rise in temperatures could lead to rapid soil thaw and a situation where “summer thaw extends more deeply than the next winter’s freeze,” according to a statement from NCAR. Such conditions can produce a talik, “a layer of permanently unfrozen soil sandwiched between the seasonally frozen layer above and the perennially frozen layer below. A talik allows heat to build more quickly in the soil, hastening the long-term thaw of permafrost.”

Melting of the permafrost — estimated to hold around a third of global soil carbon — could contribute further to warming by releasing massive amounts carbon into the atmosphere. Melting would bring other changes as well, warns Lawrence.

“An important unresolved question is how the delicate balance of life in the Arctic will respond to such a rapid warming,” he said. “Will we see, for example, accelerated coastal erosion, or increased methane emissions, or faster shrub encroachment into tundra regions if sea ice continues to retreat rapidly?”

David Lawrence, Andrew Slater, Robert Tomas, Marika Holland, and Clara Deser (2008). Accelerated Arctic land warming and permafrost degradation during rapid sea ice loss. Geophysical Research Letters, June 13, 2008

Related articles

Melting of permafrost could trigger rapid global warming warns UN February 21, 2008

Melting of the Arctic permafrost is a “wild card” that could dramatically worsen global warming by releasing massive amounts of greenhouse gases, warned the U.N. on Wednesday at a meeting in Monaco.