Saving forgotten species

Saving forgotten species

An interview with Carly Waterman, Program Coordinator of EDGE

Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com

February 28, 2008

In January 2007 a new conservation initiative arrived with an unusual level of media attention. The attention was due to the fact that the organization was doing things differently—very differently. Instead of focusing their efforts on the usual conservation-mascots like the panda or tiger, they introduced the public to long-ignored animals: photos of the impossibly unique aye-aye and a baby slender loris wrapped around a finger appeared in newsprint worldwide. The new initiative EDGE (Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered), launched by the Zoological Society of London, was not concerned with an animal’s perceived popularity, rather the chose their focal species on a combined measurement of a species’ biological uniqueness and its vulnerability to extinction. Consequently, they hoped to make celebrities out of animals (big and small) most people had never heard of: the hairy-eared dwarf lemur, anyone?

EDGE is the first conservation initiative to choose species based on their biological uniqueness. For example, while tigers are endangered they have more near-relations than the fossa. As Madagascar’s largest carnivore the fossa is the only species in its genus. This, of course, does not mean to imply that the tiger requires no further conservation efforts. EDGE merely expanded the field—a majority of its species had received little to no conservation attention to date.

In January of this year expanded its focus on mammals, adding a new program to save amphibians, which are in a state of crises worldwide. A hundred endangered amphibians were identified for conservation attention.

A year of the EDGE program has brought a lot of successes and some disappointments, but certainly the public can no longer ignore nature’s most unique animals. Carly Waterman, who has been involved in every part of EDGE as the program coordinator, spoke with Mongabay in February 2007 about EDGE’s first year, its new amphibian program, and its future.

BACKGROUND OF EDGE

Mongabay: Describe the EDGE program, namely what makes EDGE different from other environmental organizations?

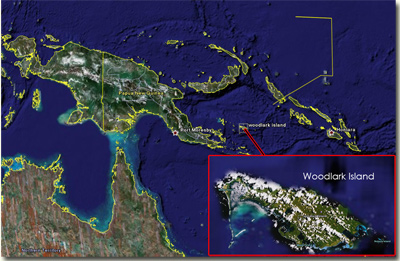

Carly Waterman: The EDGE programme is a Zoological Society of London (ZSL) conservation initiative that highlights and conserves the world’s most Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) species. These species have few or no close relatives on the Tree of Life, and therefore tend to be extremely distinct from other species in the way they look, live and behave, as well as in their genetic make-up. Examples include the curious egg-laying long-beaked echidnas of New Guinea, the human-sized Chinese giant salamander (the world’s largest amphibian) and the venomous solenodons of Cuba and Hispaniola, which are the only mammals that can actually inject venom through their teeth like a snake. EDGE species include some of the most unusual creatures on the planet, and represent a unique and irreplaceable part of the world’s natural heritage. However, our research has revealed that 70% of the top 100 EDGE mammals and 85% of the top 100 EDGE amphibians are currently receiving little or no conservation attention.

Carly Waterman |

The EDGE programme offers a new approach to prioritising species conservation action, and is the only global conservation initiative to focus specifically on threatened species that represent a disproportionate amount of unique evolutionary history. The programme is innovative in its use of the internet to raise awareness of EDGE species and highlights tangible conservation actions that will help secure their future. Supporters can follow the progress of EDGE researchers around the world on the EDGE blog, which features new discoveries, images and videos of our work.

EDGE complements rather than replaces existing conservation efforts. While focusing on protecting large ecosystems or landscapes remains fundamental to conservation, it is important not to forget about the remarkable species that we share our world with. The EDGE approach helps to ensure that these species will not slip through the conservation net and fade to extinction unnoticed.

Mongabay: Can you describe your role at EDGE?

Carly Waterman: As Programme Co-ordinator I am responsible for overseeing the entire EDGE programme which currently consists of two separate projects, one focusing on the top 100 EDGE mammals, and one focusing on the top 100 EDGE amphibians. We hope to expand the programme to include other groups as our methods and infrastructure develop further. I was involved in creating the EDGE website, which we launched in January 2007, and currently co-ordinate the programme’s research and conservation projects from my office at ZSL London Zoo.

Mongabay: How did you become interested in endangered species?

Carly Waterman: Like many of my colleagues I was initially inspired by the David Attenborough nature documentaries that were on TV when I was young. I was particularly interested in animal behavior, which I studied at university. My experiences led me to volunteer for six months on an orang utan behavioural ecology study in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo). While I was there, I saw first-hand the effect that the destruction of the forests was having on the orang utans and other species that lived in the region. I also felt sympathy for the local people who depended on the forests to make their living. It was impossible not to become drawn into the conservation issues and when my six months were up I left the project wishing there was more I could do to help raise awareness of the situation.

Mongabay: Do you have any advice for students hoping to work with conserving endangered species?

Carly Waterman: Don’t give up! It is becoming increasingly difficult to find a job in conservation, and you certainly won’t get one without lots of voluntary experience unless you are very lucky. Get as much fieldwork experience as you can and be persistent.

Mongabay: I see from your community page that you have traveled extensively, do you have a favorite place?

Carly Waterman: If it wasn’t for the mosquitoes I’d say my favourite place was the peat swamp forest in Borneo! I could never tire of listening to the sounds of the forest as the animals woke up each morning and began to call in turn. I also love the South West National Park World Heritage area in southern Tasmania, where there are caves full of glow worms, rugged forested mountains and incredibly beautiful beaches.

Mongabay: What attracted you to working with orangutans and the slender loris?

Carly Waterman: Primates are our closest relatives, so studying their behavior can lead to insights into our own. I became interested in orang utans after studying them in a Primatology course at university. Orang utans are also EDGE species, but fortunately are already receiving conservation attention from a number of organizations. The red slender loris of Sri Lanka, on the other hand, has received far less conservation attention so we wanted to help raise awareness of it and the threats that it faces, as well as help local conservation practitioners to protect it.

THE FIRST YEAR OF EDGE

Mongabay: What are some highlights of EDGE’s first year at work?

Carly Waterman: We’ve had a number of ups and downs over the past year. One of my colleagues returned from a survey of the Yangtze River in China weeks before the launch of the EDGE programme with the devastating news that our top EDGE mammal, the Yangtze River dolphin (or baiji) was almost certainly extinct. This really brought home to me the urgency of the situation. If we humans can allow a large charismatic dolphin to slip away, what chance do the “little brown jobs” have? I can’t help but wonder if EDGE had been around twenty years ago, highlighting the baiji as a top priority species for conservation attention, whether things would have turned out differently. Of course, we shall never know.

Baby slender loris |

On a brighter note, one of our expeditions last year uncovered evidence that Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna still survives in the remote Cyclops Mountains of Papua (formerly Irian Jaya) on the island of New Guinea. The species had previously widely assumed to be extinct since it was known to scientists from only a single individual, discovered in 1961. We hope to be able to continue our work in the region later this year to find out more about the conservation status of the species. Another of last year’s highlights was capturing wild long-eared jerboas on film for the very first time, and also filming the shy and elusive wild Bactrian camels that inhabit Mongolia’s Gobi desert.

We pleased to have raised sufficient funding to provide support to 8 EDGE Fellows (in-country researchers) to carry out a novel piece of research to help conserve poorly-known EDGE species. There are currently fellows working in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Mongolia, China, Liberia, Kenya and Haiti. We hope that their findings will help inform conservation strategies for the species they are focusing on, and encourage local stakeholders to become involved in subsequent conservation programmes.

Mongabay: What surprised you most in 2007?

Carly Waterman: The reception the programme received from the media and general public was incredible. We were absolutely inundated by the media at the launch last year. The programme seems to have struck a chord with the public because many of the species we are highlighting are not traditionally large and charismatic. People tend to see EDGE species as “underdogs” and nearly everyone has a soft spot for them!

Mongabay: Have you seen additional awareness of EDGE species since the program started?

Carly Waterman: Definitely. When we released the first known footage of the long-eared jerboa in the wild I imagine most people had never even heard of it. Now the species features on thousands of websites and was one of the BBC News Online’s most popular news stories of 2007. There has been a definite increase in the number of pages on the web that mention EDGE mammals and amphibians.

Mongabay: In the first year have you learned of additional/less hope for any of EDGE’s mammal focal species?

Carly Waterman: The situation looks pretty bad for the baiji, but we haven’t given up hope entirely that there could be a few survivors. There are lots of instances where animals have been brought back from the brink, where there are just a few individuals left, so perhaps there is still a chance for the species in the unlikely event that we manage to find and rescue some from the river.

Photo courtesy of Bristol Zoo Gardens |

We are hopeful that we will have a positive impact on the conservation of our other focal species. We are currently supporting a Chinese and Mongolian EDGE Fellow to work together to research the threats to the wild Bactrian camel whose range extends across the border between these two countries. We hope that the data they are collecting will lead to a conservation strategy designed by researchers and stakeholders from both countries. The Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna project is also looking promising. Local people had no idea that this species was found no place else on earth until our expedition last year. We hope that by helping to raise awareness about how special this species is, then they will take the lead in efforts to conserve it.

EDGE’s NEW AMPHIBIAN PROGRAM

Mongabay: How would you describe the response to EDGE’s new amphibian program so far?

Carly Waterman: The launch of EDGE Amphibians captured the imagination of the public once again, and we received international media coverage of the programme, which was wonderful. There is a lot of interest in amphibian conservation at the moment, as it is the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) “Year of the Frog” which is also increasing awareness of the problems amphibians are facing during the current extinction crisis.

Mongabay: Why is it important to focus on amphibian conservation?

Carly Waterman: Almost half all known amphibian species are in decline and one in every three amphibian species is currently threatened with extinction, a far higher proportion than that of bird or mammal species. Threatened by habitat destruction and degradation, the spread of virulent diseases, climate change and trade, amphibians may be on the verge of a near total disappearance from global ecosystems. These species are the “canaries in the coalmine” — they are highly sensitive to environmental changes which lead to extinction, and are a stark warning of things to come. If we lose them, other species will inevitably follow.

Mongabay: Do you anticipate that it will be more difficult to create excitement around these unique and rare amphibians than it was for the mammals?

Carly Waterman: We thought it might be more difficult, but in fact we have had a really great response to the EDGE Amphibians programme, particularly in the UK where there is currently a new documentary series highlighting the weird and wonderful world of amphibians and reptiles(the new “Life in Cold Blood” series). A lot of people want to find out more about these fascinating creatures and now, with the power of the internet, it is easier than ever to access this information.

Mongabay: What other organizations will EDGE be working with on conserving amphibians?

Fossa picture by Julie Larsen Maher / WCS |

Carly Waterman: We are working with other organizations on a number of different levels. Our practical field conservation projects will link with in-country conservation organizations and local researchers, while our awareness campaign will complement global campaigns, such as WAZA’s Year of the Frog campaign and Amphibian Ark (which aims to initiate captive breeding programmes for those species that are most threatened in the wild).

Mongabay: Do you have a favorite amphibian from the list?

Carly Waterman: That’s a difficult question. I like the purple frog (Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis), ranked 4th on the list, which spends most of the year up to 4 metres underground, only surfacing to breed in the rainy season. I am also fascinated by Myer’s Surinam toad (Pipa myersi), ranked 27th, which reproduces by allowing its tadpoles to develop embedded in the skin of the mother’s back. The species apparently has the uncanny ability to look almost putrefied even when at the peak of good health. In his 1954 book “Three Tickets to Adventure”, the naturalist Gerald Durrell described a large female Surinam toad with the words “…looking — as all pipa toads look in repose — as though she had been dead for some weeks and was already partially decomposed.”

THE THREATS AND CONSERVATION OF ENDANRGERED SPECIES

Mongabay: By working with so many varied endangered species across the globe, what do you see as the main drivers of extinction today?

How activists and scientists saved a rainforest island from destruction for palm oil |

Carly Waterman: Human alteration of habitat is the biggest single threat to plant and animal species. Pressure on global ecosystems is intensifying as global populations rise, settlements expand, and natural resource extraction accelerates. It is now estimated that humans have altered between one third and one half of the Earth’s land surface. Other threats include introduced and invasive species, overexploitation for the food or pet trade, pollution and climate change. Almost all of these factors are driven by human activities.

Mongabay: What can concerned citizens do to help endangered species?

Carly Waterman: In general we have to try and have a lighter impact on the environment to help conserve all species. We can help reduce our impact by using fewer resources, reusing and recycling; voting for politicians and decision makers that make the environment a priority; purchasing products from companies that make the environment a priority; investing in companies that make the environment a priority; helping ensure that environmental issues are prioritised in the educational system; and supporting organizations that are working to conserve the environment

WHAT’S IN THE FUTURE FOR EDGE

Mongabay: What do you hope for the organization (and conservation in general) in 2008?

Carly Waterman: So many people feel overwhelmed by the environmental problems we are facing today that it is important to highlight the smaller actions that everyone can do to reduce their impact on the planet. The EDGE website presents tangible solutions to the problems faced by the world’s EDGE species so that people feel inspired to do something to help. I hope that people will continue to support the programme this year so that we can achieve our aims and implement conservation projects for the focal mammal and amphibian species. More generally, I hope that by raising awareness of the weird and wonderful species with which we share our planet we will inspire people to live more sustainably into future.

Mongabay: What should we anticipate for 2008 at EDGE? Any particular expeditions etc.?

Carly Waterman: Our first expedition of 2008 is to Liberia, where we are establishing a camera trapping project to monitor the pygmy hippopotamus. Although well represented in zoos around the world, very little is known about this cryptic species in the wild and we hope to find out more about its conservation status by camera trapping it in its natural habitat. Over the next few months we are hoping to undertake expeditions to Thailand, to establish a bat monitoring project focusing on the bumblebee bat and Sri Lanka, to find out more about how to help local researchers to protect the red slender loris. We are also planning a number of expeditions focusing on amphibian species such as the Chinese giant salamander and the lungless salamanders of Mexico.

Mongabay: Will new mammal focal species appear this year or next?

Carly Waterman: We are investigating new mammal projects and hope to announce some on the website soon.

Mongabay: Has research already begun on the top 100 EDGE birds for 2009?

Carly Waterman: Yes — we hope to be able to launch EDGE Birds in January 2009.

Mongabay: Finally, the task EDGE has taken on for itself (to help conserve 200—so far—unique and endangered species) is so massive: how do you do it?

Carly Waterman: We are focusing primarily on the species that are currently receiving little or no conservation attention (70% of the top 100 EDGE mammals and 85% of the top 100 EDGE amphibians). Of course, we cannot hope to save them all ourselves. EDGE represents to first step to achieving conservation action for these forgotten species. EDGE puts species such as the long-eared jerboa or Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna on the map by raising awareness of their plight, both amongst local people and internationally. We then develop appropriate conservation strategies in collaboration with local researchers. A large part of the programme is focused on increasing conservation capacity in the countries in which EDGE species occur, through supporting and training EDGE Fellows to undertake research into the focal EDGE species. By providing support and advice to local organisations so that they can incorporate EDGE species into their existing programmes we aim to ensure that each project remains sustainable into the future.