Scientists propose conservation areas for the unique island of Sulawesi

Scientists propose conservation areas for the unique island of Sulawesi

Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com

January 6, 2008

Little-known Sulawesi may be the world’s most strangely shaped island: with four large peninsulas jutting outward, the island could either resemble a mangled lower-case ‘k’ or an upside-down emaciated mermaid—depending on one’s perspective. However when Dr. Charles Cannon states that the island is “one of the most unique spots on Earth”, he is not referring to Sulawesi’s shape but its ecology.

Also known as Celebes, Sulawesi is a part of Indonesia, resting between Borneo and the Maluku Islands. The island’s interior is mountainous and forested, while the coastal areas contain most of the island’s 15 million people. While the island is one of the least researched areas in Indonesia by scientists, what is known proves its biological wealth. Sixty-two percent of the mammals recorded on Sulawesi are endemic. One of the strangest is the world’s smallest wild cattle, the Lowland Anoa, which is classified as endangered by the IUCN. Its population continues to decline—mostly because of hunting—with estimates at 2,500 individuals. Thirty-four percent of birds are also endemic; the most famous here is the Maleo. This endangered bird is the only member of the genus Macrocephalon. Although it has been protected under the Indonesian government since 1972 the species’ population continues to decline.

|

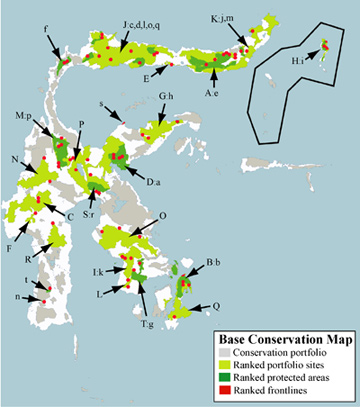

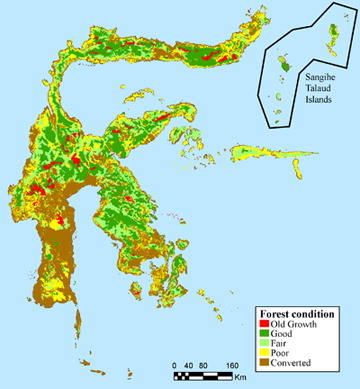

Dr. Cannon—who visited the island in 2004—and several other scientists intensively studied the island’s geography for the environmental organization, Nature Conservancy. They planned to determine the best places for conservation efforts. Using data from numerous sources the group looked at forest type and condition, current protected status, and the possibility of change to forests to determine the best places to protect. The study found that thirty percent of the island’s forest could be classified as in great to good condition, while one half of the forests was either poor or converted for human use. The vast majority of undamaged forests lay in Sulawesi’s high lands where agricultural and land conversion proves far more difficult; only a small part of the lowland forests remained intact. The study came up with a list of twenty areas recommended for conservation. Asked to name which area he most wants to see preserved, Dr. Cannon chose two: “I would say the lowland area in the northern arm and the Morowali region.” The lowland forest to which he refers is the largest area of undisturbed lowland forest on Sulawesi. Dr. Cannon adds that “there are some logging companies there for sure”.

Boletus species at roughly 500 meters of elevation

All photos by Chuck Cannon |

The study stresses that one of the most important issues surrounding the preservation of Sulawesi is just how little science actually knows about the island. For example, collection rates of plants on island remain one of the lowest in Indonesia, and new species are continually popping up, like the Togian Hawk-Owl, discovered in 1999, a new species of tarsier in 2001, fifteen new beetles uncovered in 2005, and new plant species are continually reported. Dr. Cannon lists several reasons why the biologically-rich island is so under-researched: “historically, Sulawesi has never been a major production area for exports, like timber, or plantation crops, like oil palm, and therefore major economic and infrastructural development projects have largely passed it by. While development means degradation and exploitation of natural resources, they also bring a certain attention to an area and contact with the outside world.” In line with this thinking, Sulawesi has long been under the shadow of its larger and imposing neighbor, Borneo. Dr. Cannon also points out that researchers are more likely to travel to places that have a history of research for sensible reasons: “It is not easy to conduct detailed biotic surveys, either logistically in the field or technically in the museum. The places with a strong network of active workers and a deep history of research will naturally be chosen over those which have no such advantages.” Due to its rugged geography travel in Sulawesi is “difficult, time consuming, and expensive”. It must also be noted that the island comes with its own perils: it “has been plagued by tensions between Christians and Muslim populations for over a decade” and its seas contain “some of the most active pirates in the world”.

Due to its unique geography, Sulawesi has held off some of the agricultural pressures facing the rest of Indonesia. Dr. Cannon explains that “the sheer ruggedness of the landscape and the generally poor soils will protect them against the lazy, but conservation on the island continues to lag behind other spots in Indonesia.” Perhaps this lag is due to the fact that the island has remained off the international radar for so long. The one agricultural initiative the island has supported was shade coffee: “the understory was being cleared to grow coffee plants. While this is much better than total conversion, the understory is basically destroyed and changes the regeneration of the forest.” While suitable for coffee the island’s almost impossible geography has helped it ward off one of the biggest threats to forests in Asia and the Pacific: oil palm grown for bio-fuels. Dr. Cannon refers to the conversion of forest into agriculture for bio-fuels as “crazy”, and he worries that “the unwise and rich” will look “for some big investment and [pay] to clear large areas without realizing that it will not be profitable in the long run, so that no long term benefit to the local economy occurs, the forest is gone.”

Dr. Cannon tries “to remain optimistic” about the future of Sulawesi’s forests, and in particular the twenty areas pointed out in the study. He states that from his experience most officials “have their heart in the right place” but ” they are often between a rock and hard place and almost can’t avoid being against conservation. If we could figure out reasonable alternative incentives for these people, things would improve but creating these incentive structures often require major social reorganization.” Hope may come in the UN’s burgeoning incentive to pay nations to conserve their forests, entitled REDD. Dr. Cannon states that “if forests could be brought into the climate equation, which they obviously should be, things could improve for Sulawesi” and hopefully the areas proposed in his study could be conserved for generations to come.

Citation: Charles H. Cannon, Marcy Summers, John R. Harting, and Paul J.A. Kessler (2007). Developing Conservation Priorities Based on Forest Type, Condition, and Threats in a Poorly Known Ecoregion: Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biotropica.

MORE ARTICLES ON SULAWESI

Rare and mysterious forests of Sulawesi 80% gone. Roughly 80 percent of Sulawesi’s richest forests have been degraded and destroyed for agriculture, logging, and mining, reports a ground-breaking assessment of the Indonesian island’s forests.

Fruit-eating birds at particular risk from Indonesian deforestation. A new study on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia confirms the critical importance of fig trees to the rainforest ecosystem. The research has implications for wildlife conservation in an area of high rates of forest loss from agricultural conversion and logging.

Farming in the rainforest can preserve biodiversity, ecological services. While conversion of tropical forest for agriculture results in significant declines in biodiversity and carbon storage, an analysis of Indonesian rainforests shows that farming cacao under the partial shade of high canopy trees can provide a way to balance economic gain with environmental considerations.

Traditional customs pit young versus old in Indonesia’s Torajaland. The Torajanese people of Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, have long been renowned for their extravagant celebrations of the dead in funerals, graves, and effigies. Just outside of Rantepao, the regional capital of Torajaland, ostentatious and costly funerals take place often. But increasingly, such rites are dividing generations. As in other indigenous cultures around the world, a growing rift between the young and old is calling the foundations of tradition into question.