A new study warns that the simultaneous effect of habitat fragmentation, overexploitation, and climate warming could increase the risk of a species’ extinction.

Writing in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, a team of scientists led by Camilo Mora at Dalhousie University, report that experiments with microscopic rotifers (a type of zooplankton) show that working in concert, these threats pose a much greater extinction risk than acting alone. In other words the threats had a multiplicative effect when they occurred simultaneously.

“Our experiment clearly shows that exploitation, habitat loss ad warming are equally capable of causing significant population declines,” said Mora. “More importantly, our results showed that the stress induced by any one threat impairs the ability of populations to resist or adapt to other threats. Populations exposed to more than one threat declined drastically. Population declines were up to 50 times faster when all threats operate at their maximum extent upon a given population.”

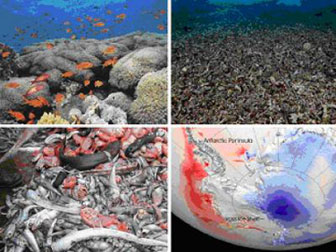

The viability of many marine and terrestrial species could be impaired due to interacting human activities that cause the loss of species’ habitats, overexploitation of their populations and warming of their environments. Credit: Top left: John Veron from Corals of the World. Top right: Wolcott Henry/Marine Photobank, Bottom left: Steve Spring/Marine Photobank, Bottom right: NASA-GSFC/Marine Photobank. |

“It is hard to think of a system that would not be exposed to several threats at once,” added Nancy Knowlton of from the Scripps Institute of Oceanography. “Coral reefs, as an example, are being overexploited to satisfy food demands and the trade of ornamental species. They are also harmed by blast fishing, coastal development and pollution, all of which directly or indirectly kill the corals and leave them vulnerable to erosion and loss of their complex matrix. Habitat loss is also occurring in areas that are very important to the ecological functioning of coral reefs such as estuaries and mangroves. Finally, it, is the widespread effect of ocean warming, which is evident by the regional to global scale patterns of coral bleaching and mortality when temperature increases only few degrees. It is not surprising then that in regions like the Caribbean, where coral reefs are relatively well monitored; up to 80% of the coral cover has been lost in recent times. Similar rates of decline have also been reported for estuaries, mangroves, and coastal and oceanic fish communities.”

“An accelerated decay in biodiversity due to interacting human-threats has been long suspected among ecologists and conservation biologists,” Mora added. “This study reveals the potential for multiple threats to enhance each other effects. Now we have an idea of the speed at which populations can decay when exposed to several threats.”

In the face of scientific uncertainty, the scientists urged taking a precautionary approach and recommended mitigation policies that reduce human threats to biodiversity.

Citation: Mora C, Meztger R, Rollo A, Myers R. (2007) Experimental simulations about the effects of overexploitation and habitat fragmentation on populations facing environmental warming. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.0338)

Related

Just how bad is the biodiversity extinction crisis?

In recent years, scientists have warned of a looming biodiversity extinction crisis, one that will rival or exceed the five historic mass extinctions that occurred millions of years ago. Unlike these past extinctions, which were variously the result of catastrophic climate change, extraterrestrial collisions, atmospheric poisoning, and hyperactive volcanism, the current extinction event is one of our own making, fueled mainly by habitat destruction and, to a lesser extent, over-exploitation of certain species. While few scientists doubt species extinction is occurring, the degree to which it will occur in the future has long been subject of debate in conservation literature. Looking solely at species loss resulting from tropical deforestation, some researchers have forecast extinction rates as high as 75 percent. Now a new paper, published in Biotropica, argues that the most dire of these projections may be overstated. Using models that show lower rates of forest loss based on slowing population growth and other factors, two respected scientists say that species loss may be more moderate than the commonly cited figures. While some have criticized their work as “overly optimistic,” prominent biologists say that their research has ignited an important discussion and raises fundamental questions about future conservation priorities and research efforts. This could ultimately result in more effective strategies for conserving biological diversity, they say.