Indonesia now has the highest deforestation rate in the world, topping even Brazil which has more than five times the natural forest cover. Background photo: rainforest in Sumatra.

Despite a high-level pledge to combat deforestation and a nationwide moratorium on new logging and plantation concessions, deforestation has continued to rise in Indonesia, according to a new study published in Nature Climate Change. Annual forest loss in the southeast Asian nation is now the highest in the world, exceeding even Brazil*.

The study, led by researchers at the University of Maryland (UMD), is based on analysis of high resolution satellite data. Unlike previous research, the new paper distinguishes between loss of natural forest — which it calls “primary forest” — and cyclical harvesting of industrial plantations.

The study finds that Indonesia lost more than 6 million hectares of natural forest between 2000 and 2012. Worryingly, forest loss is trending upwards in the country despite hundreds of millions of dollars being spent by donors and the government on programs to cut deforestation. Deforestation was highest in 2012, the last year of the study.

Forest loss in Indonesia and the Brazilian Amazon between 2001-2012.

Indonesia lost 15.79 million hectares of forest between 2000 and the end of 2012, according to the study. Of that area, 38 percent or 6.02 million hectares consisted of natural or “primary” forest.

“We quantified increasing loss of primary forest during the moratorium, meaning the moratorium has not yet slowed clearing and may in fact have accelerated it,” Belinda Margono of UMD and the Ministry of Forestry told Mongabay.com. “Forest loss in 2012 was higher in Indonesia [840,000 ha] than it was in Brazil [460,000 ha].”

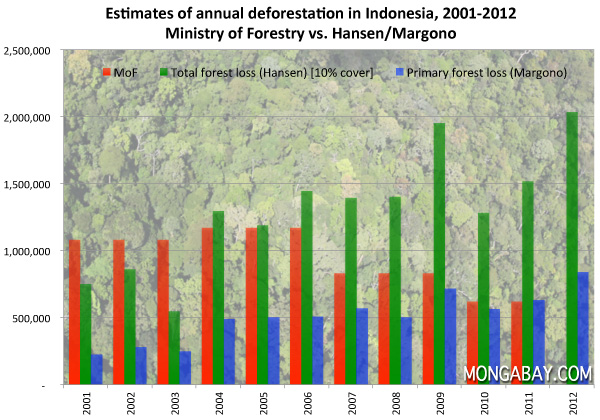

The results contrast sharply with the Indonesian government’s claims that deforestation has declined rapidly in recent years. Part of the reason for the discrepancy stems from how Indonesia’s Ministry of Forestry classifies forest cover and loss. The ministry counts industrial plantations as forest cover and only measures loss in areas that are designated as being part of the “forest estate”, which covers more than two-thirds the country’s land mass. Forest clearing that occurs outside the official forest estate is therefore not included in official estimates.

Last year the Ministry of Forestry released estimates that differ markedly from UMD data.

Nonetheless within the official forest estate the study still identified a trend of increasing forest loss especially in areas zoned for industrial conversion, typically for acacia and eucalyptus plantations. But the study also found rising deforestation in areas where clearance is restricted and prohibited by law: production, conservation, and protection forests.

“Almost 40% of total primary forest loss within national forest lands occurred within land uses that restrict or limit clearing, 22% in limited production forests that restrict clearing and 16% within conservation and protection forests that prohibit clearing,” the authors write.

Rainforest in Aceh, Sumatra. The finding that selectively logged forests are more likely to be cleared than old-growth forests is consistent with other research. Forests that have been stripped of their high value timber are significantly less valuable for commercial exploitation, increasing pressure to clear them outright for industrial plantations.

More than half of loss (3 million hectares or 51 percent) occurred in lowland forests, the most endangered of Indonesia’s forest types. But forest loss in wetlands areas increased at an even faster rate, accounting for 2.6 million hectares or 43 percent of loss overall.

“Easy access to lowland forest has made primary forests a target for logging and the subsequent conversion to higher value land uses. Wetland forests in Indonesia have historically remained largely intact. However, during the past two decades the conversion of wetland forests, including peatlands, to agro-industrial land uses has increase.”

Wetlands forest loss was particularly pronounced in Sumatra, where peatlands are increasingly targeted for industrial plantation expansion for palm oil and pulp and paper production.

“More intensive appropriation of wetland landscapes is found in Sumatra compared with Kalimantan or Papua, possibly reflecting a near-exhaustion of easily accessible lowland forests,” they write. “Primary wetland forest loss during the study period in Sumatra totaled 1.53 million hectares compared with 1.21 million hectares in lowland forest.”

Sumatra also had the highest total area of natural forest loss at 2.86 million hectares. Kalimantan, as Indonesian Borneo is known, followed with 2.38 million hectares. Sulawesi was third with 396,000 hectares of loss during the period.

Carbon emissions from deforestation and peatlands degradation make Indonesia the world’s third largest greenhouse gas emitter in some years.

Papua, the Indonesian half of the island of New Guinea, lost only 261,000 hectares despite having the largest area of surviving forest cover in Indonesia. The authors note that Papua is at “a more nascent stage of forest exploitation” compared to other major islands in Indonesia.

Virtually all of natural forest loss occurred in previously logged areas, indicating that commercial logging remains an important driver of deforestation in Indonesia. Old growth or “primary intact” forest accounted for only two percent of loss during the study period.

Indonesia’s forests are home to many endangered species, including orangutans

All told, the results indicate the Indonesia’s much-heralded efforts to slow deforestation aren’t yet enough to reverse the country’s sky-high rate of forest loss. These efforts, which have been backed politically by Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and financially supported by Norway, include a push to reform the bureaucracy that manages the country’s forests and a national moratorium on new concessions across some 14 million hectare of forests and peatlands.

But while seemingly well-intentioned, the moratorium was heavily criticized from the outset by environmentalists for failing to extend to existing concessions. That exclusion left millions of hectares of forest up for clearing. Meanwhile loopholes for mining and energy crops like sugar cane meant that large areas could still be excised from the off-limits zones.

The authors say their findings indeed suggest that the moratorium is failing to reduce deforestation.

“Although Indonesia recently implemented an implicit deforestation moratorium, beginning in May 2011, it seems that the moratorium has not had its intended effect,” they write. “In fact, the first full year of this study within the moratorium period, 2012, experienced the highest rates of both lowland and wetland primary forest cover loss. Questions concerning the moratorium as a driver of increased deforestation are worthy of investigation.”

There are several factors that could be driving deforestation higher in Indonesia despite the moratorium. Commodity prices have rebounded since the global financial crisis, providing a strong financial incentive for increased forest conversion. Additionally, the fear that the moratorium could eventually be extended to existing high carbon stock lands could be encouraging concession holders to clear forest while they still can.

Nonetheless there are some encouraging signs for Indonesia’s forests. The President’s push to reform institutions that manage forests is finally underway with the establishment of the REDD+ Agency, which endeavors to enact cross-cutting changes to support programs to reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation. At the same time, a series of decisions in Indonesian courts have strengthened indigenous claims to forest lands and found companies liable for damage they’ve caused to forest areas. Mostly importantly however, the private sector has begun to take a leadership role in better forest management. In the past three years, Indonesia’s largest palm oil and pulp and paper companies have established zero deforestation policies that commit them to protect high carbon stock forests and high conservation value areas. Those companies, including Golden Agri Resources and Asia Pulp & Paper, are now pushing the government to enforce laws that support these policies.

Beyond these measures, transparency around Indonesia’s forests is also improving. Earlier this year, the World Resources Institute, in partnership with UMD, Google, and dozens of other organizations and institutions (including co-authors of the Nature Climate Change paper), launched Global Forest Watch, a tool that maps the world’s forests. In Indonesia, Global Forest Watch includes previously undisclosed data on forestry concessions as well as information on conservation areas. It also includes a deforestation alert system and NASA fire data that provide monthly information that could enable the government to take action on deforestation as it happens. But doing so will require stronger political commitment, according to Margono.

“On a technical level, we have a good working relationship with the Ministry of Forestry,” she said. “The politics of official estimates and data sharing are another thing.”

Deforestation in Riau Province, Sumatra, Indonesia in February 2014.

* In asserting that Indonesia had the highest deforestation rate in the world, the study excluded forest loss outside the Brazilian Amazon. When deforestation in Brazil’s other forests — the caatinga, cerrado, and Mata Atlantica — is included, its forest loss exceeds that of Indonesia.

CITATION: Belinda Arunarwati Margono, Peter V. Potapov, Svetlana Turubanova, Fred Stolle and Matthew C. Hansen. Primary forest cover loss in Indonesia over 2000–2012. Nature Climate Change. PUBLISHED ONLINE: 29 JUNE 2014 | DOI: 10.1038/NCLIMATE2277